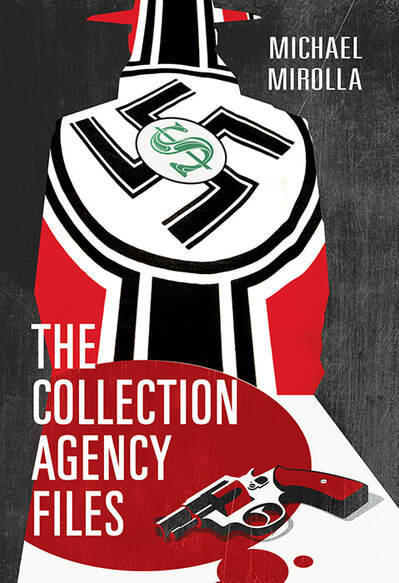

Michael Mirolla's The Collection Agency FilesReviewed by Nicole Yurcaba

Could something more sinister and even more evil than the Nazis exist? In Michael Mirolla’s The Collection Agency Files, that question emerges, and by carefully weaving historical anecdotes with alternative history speculations, the book speculates about what the world might resemble if fascism remains unchecked.

The sleek book opens with “Item One: At the Wall—A Letter.” Addressed intimately to “Adolf,” the mysterious letter opens with a brief confession of loneliness, of an awareness that moments exist in which one feels “quite alone” and “there seems to be no one else in the entire universe.” The letter jarringly shifts from philosophical insights like this to “A tiny confession,” in which the speaker details the visits of an “occasional visitor” who wears “clean and perfumed silk garments” beneath a military-cut coat and removes her wedding ring prior to entering the speaker’s room. The story develops a baseness, and the speaker also divulges the isolation in which they operate as they live “at the wall” and news—even “the most remote grasp of the empire”—is nil. The speaker’s admission of sensory and intellectual deprivation alludes to the iron-clad methods to which fascist and authoritarian governments resort in order to control entire populations. Thus, the story develops a relevant eeriness, especially as one considers the real-world news and media regulation occurring in countries like Russia and China. As the collection continues, more details about The Collection Agency and its files emerge. The Collection Agency operates on the motto “‘No Debt Too Small; No Debtor Too Large.’” Its foremost agent, a “master of disguise and one of the most valuable Agents in the field,” is a steadfast character throughout the remaining stories. Claudius is quite fascinating. At times, he seems agreeable to his duties with The Collection Agency, and at others, he seems like a mole, a defector. This duality makes him the collection’s most fully developed character, a character who “delighted in playing” the game of cat-and-mouse, especially as he frequently places “the dangerous evidence right under the very noses of those who would have slit his throat without a second thought had they known.” Claudius’s role in the stories is also unique in that he is representative of what the human spirit can—and will—endure during times of socio-political duress. The manipulation of human will and the human condition is another stark theme in the book. In “Item Two: The Debt—A Memorandum,” this conversation emerges as the speaker reflects on the role of war and its significance for the Agency. The human cost is first and foremost, since any “able-bodied man who becomes an Agent is immediately exempted from the draft.” War’s negative impact on the Agency becomes clear. The speaker details how the Agency had “difficulty with recruitment” and therefore “accepted anyone who displayed a willingness to do the work.” Thus, the many Agents “turned out to be second-rate” and “unable to adapt to the changing times and useless for the task at hand.” Other Agents participate in deep-running corruption activities, such as “accepting kickbacks to alter the files, lending money out on their own at exorbitant rates verging on the usurious.” It proves itself to be a system which ultimately eats itself, since the ongoing corruption and its other fallacies eventually cause the higher powers who control it to subject it to a mass purge in order to reorient its role in the government. Even though The Agency relies on a lack of confidentiality, readers never learn about the mass purge’s details. This lack of explanation and evidence adds to the book’s sinister tone and content. The book also carries a stark warning about what happens to governments and entities that are allowed to grow, thrive, purge, and dominate unchecked. The Collection Agency, at one point, presses “the government for more rights and powers,” which the speaker describes as “not asking for much.” The Agency’s expanded rights would include “the right to search suspected homes without the need of a warrant” and “the right to allow its Agents to carry weapons.” The Agency also demands that the government allow Agents to “seize property on the spot, merely upon proof that the person is indeed the debtor in question.” The property seized by Agents should be “any property owned by the debtor and not only the item or items in question.” Thus, this focus on the Agency’s expanded rights reminds readers about the violent, and frequent, overreaches fascist entities take as they work to gain control of every aspect of an individual’s existence. Even more alarming is the resonance with American new which frequently features headlines about former President Donald J. Trump’s call for loyalty tests within the federal government should he be reelected, his continued denial of the 2020 election results, and his concerning influence on America’s Republican Party. Thematically, in its own Kafka-esque way, The Collection Agency Files resonates with Zachary C. Solomon’s A Brutal Design. Its stories might bear a historical setting. Nonetheless, their thought-provoking prose and surreal stories remind its audience that democracy and free will, even in modernity, dangle by a precarious thread. Nicole Yurcaba (Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian American of Hutsul/Lemko origin. Her poems and reviews have appeared in Appalachian Heritage, Atlanta Review, Seneca Review, New Eastern Europe, and Ukraine’s Euromaidan Press, Lit Gazeta, Bukvoid, and The New Voice of Ukraine. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University, and is the Humanities Coordinator at Blue Ridge Community and Technical College. She also serves as a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and Southern Review of Books.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us