|

It’s hard to complain about Signal Editions. The poetry imprint of Montreal’s Véhicule Press has for decades published strong collections by a range of familiar authors as well as new voices. Also notable is the fact that the sensibilities of its editor since 2001, Carmine Starnino, are present on nearly every page they publish. This near symbiosis is itself an achievement. But the widespread acclaim for the imprint could be regarded as at odds with the (at least until recently) quite divisive nature of the editor himself.

The three titles that make up Signal’s Spring 2021 season are as meaty as what we might expect from the press. But those tensions—between commitment to a singular poetics and a good range of writing, and, by extension, to the tastes of one man and the obligation of a Canadian publisher to represent a variety of voices—are visible in the books. At times, it’s as if those signature characteristics of chiming internal rhyme and consonance, metrical swagger, syllabic limits, and turned phrases are packed together so solidly that, underneath the impressive music, one can hear the tightening of the Signal screws. This effect is most apparent in the opening poem of Chad Campbell’s Nectarine. “The Pheasant” features those repeating phonetic elements in abundance, but the excess is matched by a compactness. The first line’s assonance sets the tone (“The pheasant bled out in a field of heather”) for what seems less a poem than an intoxicating riddle—a coil of sound so tight that, by its final five lines, its ability to carry syntactical meaning seems almost miraculous:

It makes one wonder whether there a strict constraint on which phonemes are allowed, or a closed form that’s being miniaturized—is it a truncated villanelle, its rhymes and repetitions compressed until they ring from within the lines?

“Funk Island” is a little looser, but it uses the same sonic playbook to outline similarly elemental rhythms and antimodernist content (“This is not industry. Not the gear of / some machine chugging coal shadows / that walk into walls and never come back”). It’s well within the Signal wheelhouse, but slackening things even a little gives the impression that the poems are lapsing into the less formally adorned free verse Starnino has often maligned. “Sanders Rare Prints” uses its repeating parts to engage with time and perception. The lines “It’s one thing I like about drinking / slowly but with persistence, to feel—as I look / again—the looking might not have to end” employ alcohol to get at this nexus, something that appears again in some of the book’s later poems. But it’s that concluding twist of the timely turned phrase that becomes a trademark. It happens again and again, with “Tunnel Walking” and “Big Red Hills” among the most notable instances. The more understated finish of “Town Field and Sky” gives us a picture of the poet as cyborg-efficient: “My mind won’t stop working. / It ticks like an engine in the cold.” Medrie Purdham’s Little Housewolf adds layers of disorientation to the repertoire. By disorientation I mean not odd images or syntactic disruption, but rather a more fundamental, philosophically minded tinkering with perspective, time, space, action, and object. It’s as if Purdham were playing familiar Language games of swapping out words, only with bigger building blocks of knowing and being. “Hinge” combines these alien qualities with enough sonic resonance to locate it well within Signal’s horizons. Lines like “And every day we came home from over-the-way, / every day at the same time. Each to his identical little plot / piled high with long mouldy hay and lost plumage // and wondered if this would be the day the gate fell” anchor the syntactical turns with a familiarly steady cadence. Even the titles of several poems—“Hinge,” “Carapace,” “Bower”—refer simultaneously to objects and ideas, splitting the difference between the impressionistic and the documentary (from “Carapace,” “Let me show you this one’s underpanel— / just slide your thumb in right there— / this keystone piece in the middle, leathery, / is called the apron”). “The Tilled Field” teems with activity. Based on the painting by Joan Miró, it’s picaresque in the way an 8-bit RPG might be described as such. It advances smoothly from encounter to odd happening, its larger environment seemingly frozen in time and space:

The names of the sections of “Studio Animals”—“Marmoset,” “Ermine,” and “Tamarin”—with their harmonies and blurring connotations infuse sense itself with uncertainty. The end of the poem seems to gather the ragged ends of memory and knowledge:

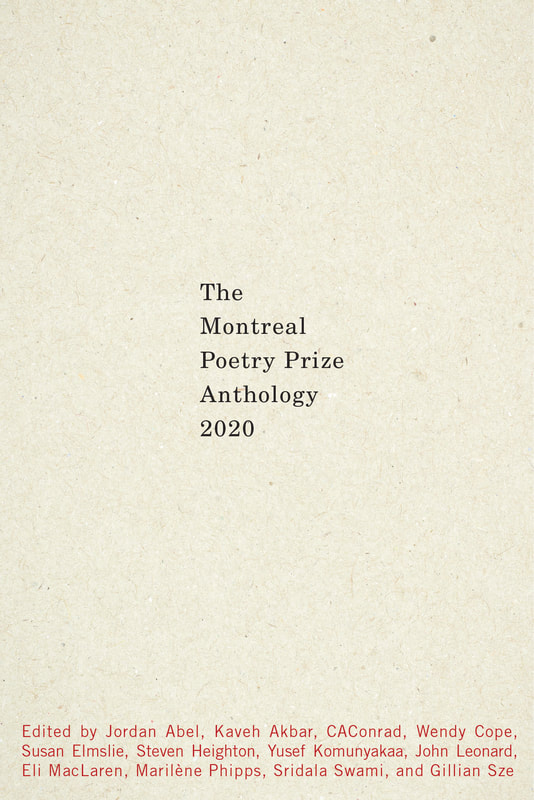

The Montreal Poetry Prize Anthology 2020 most sharply highlights the contradictions between an identifiable aesthetic and an open-to-the-world eclecticism. This shouldn’t be controversial to say given that its very existence conceives of poetry in both aspects. Formerly called the Global Poetry Anthology and now based at McGill University, the collection is edited by eleven poets from throughout the Anglosphere plus McGill scholar Eli MacLaren; the selections come from 4,645 entries received from 107 countries, according to MacLaren’s preface.

The preface frames the book as a locally stamped poetry of the world, or “a window into the currents and breezes of contemporary poetry as they are stirring in English around the world today.” MacLaren characterizes each poem as the work of “someone hammering pain into a rectangular type of courage,” making matters still more practical by expressing his desire that “this inexpensive book [might] in turn repeat the precept that poetry is for everyone.” It’s a sophisticated way of packaging the paradoxes sustaining contemporary poetry—the invitingly expansive nature that must coexist with standards of quality that are necessary to sustain it and yet sometimes demonized as elitist. The citation for the winning poem, selected by Yusef Komunyakaa, deals in more familiar power-of-poetry ideas. Victoria Korth’s “Harlem Valley Psychiatric Centre” is described in terms of need, empathy, reckoning, and witnessing, as if the accolade requires a poem to enact some real-world goodness. Unfortunately, the book’s alphabetical sequencing notwithstanding, the first handful of poems takes us into Feed the World territory. Amber Adams’ “The Battle of the Eclipse” refers to war in Iraq and ends with “a boy / looking up at the sky with a pinhole / camera made of cardboard and aluminum foil.” Ra Avis’ “The First Thing I Ever Learned to Draw Was a Bomb,” with its shrapnel and body parts and Laotian children, combines lyric and spoken-word sensibilities to send a pretty clear message. The sequencing yields interesting shifts in quality: Sadiqa de Meijer’s “Brother in Flight” is a noticeable departure from many of the preceding poems. The run continues with the brevity and tightness of Luke Hankins’ “Category Error”: “The sleek, streaked coat of the tiger. / The iridescent scales of the snake. / The shockingly blue eyes / of the shooter on the evening news.” Korth’s poem is part of this streak, its switches from the indicative to the imperative (“One needs to be a little lost to find it / on a Dutchess County knoll. Building 85 / still stands. Look it up. Or better, go yourself”) creating a compelling sense of space and justifying Komunyakaa’s praise. Yet it too becomes a family narrative by the end, fitting with the book’s emphasis on poems one might expect to resonate with a larger audience. The pitch works for Korth, and for Caitlin Heiligmann’s “Maybe,” which combines straightforward thoughts about impostor syndrome with a casual formal tightness (“If I do all the readings / carefully, diligently annotating / everything that could be important…”). Other poems, about fathers, sons, disappointment, and Irish genes, might grate on readers who are more familiar with contemporary poetry and its wider range of topics. The expansive nature makes for some surprising moments. Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s “Massgirl” slices through the anthology’s carefully curated universalism: “I am totally massgirl / I can’t help it / I ride with the top down / I listen to Robyn / I will cut a bitch.” Like Purdham’s tilled field, the book’s many moving parts are made up of sharp objects and miraculous moments, along with its share of wreckage. Carl Watts holds a PhD in English from Queen’s University. His research interests have included whiteness and constructions of mainstream and experimental poetry. He has published poems in journals such as The Cincinnati Review, The Cortland Review, and The Manchester Review, and in a chapbook, REISSUE (Frog Hollow Press, 2016). He is on Twitter @carl_a_watts.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us