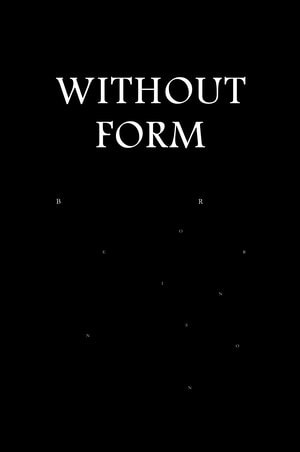

Without Form

|

|

The title of Ben Robinson's book-length conceptual poem, Without Form, references the opening verses of the Hebrew scriptures. The passage in question reads, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form, and void; and darkness was on the face of the deep." The biblical account goes on to represent God speaking into that void in order to create the world, establishing a close connection in Jewish and Christian thought between the divine Word and the formation of the created universe.

The body of Robinson's poem speaks directly to this connection between word and form, taking the King James Bible in its entirety and erasing everything except the chapter and verse numbers, or, more precisely, whitening everything else out, so that it becomes indistinguishable from the page but still provides shape for the visible numbers. The reader is confronted by mostly blank pages, scattered with numbers that have no obvious meaning, appearing like some obscure set of coordinates. My primary attraction to this project was visual at first, the minimalism of it. For me, that's where the power was. This erasure of the biblical text is, on at least several figurative levels, an erasure of the divine Word. It's a gesture that returns the text to a state, as the book's title suggests, that is without form. Robinson gives us a Bible that has no visible divine Word, a Bible that is all absence and void.

In biblical terms, this return to the void is explicitly apocalyptic, as when Jeremiah warns the Israelites of the coming wrath of God. "I beheld the earth," Jeremiah says, himself referencing the first verses of Genesis, "and indeed it was without form, and void; and the heavens, they had no light.[...] Yet I will not make a full end [...] because I have spoken." It is only this speaking, this divine Word, that keeps the world from a destruction so complete that it can only be compared to the state of formlessness that preexisted creation. Without the divine Word, there is no form. Formlessness and void is what comes both before the Word speaks creation and after that Word is withdrawn. And yet, although Robinson erases the text, keeping only the paratext of chapter and verse, form still remains. The numbering of chapter and verse imposes a structure of its own, and it also occupies a form on the page. It holds the space of the visibly absent text, maintaining the limits of the absent Word. Where the text once was, and where it might be once again, the paratext of chapter and verse keeps the contours of a divine Word that is now only present in a kind of absence, the shape of what once was or what might come to be, either memory or potentiality. When I see those numbers on the page, they're at once constrictive and unrestrictive. Visually they're a grid, but also free and floating. In this way, the paratextual elements call attention to the profoundly human and mundane forms that allow the divine Word to appear at all, from the obvious structures of chapter and verse, to the almost forgotten structures of the alphabet itself, of punctuation, of lineation, and, perhaps most relevant here, of space. These human interventions are not absence and void, but neither are they the divine Word itself. They are the almost unseen structures that nevertheless make space for the Word to appear.

This is most obvious in the fact that Robinson's poem does not reject the Word entirely. Rather it diligently keeps the space of the Word, accounting for it literally by chapter and verse, following its absent contours with the greatest precision, not so much erasing it even, but only changing its colour to make it indistinguishable from the page. The divine Word is neither present, but neither is it absent. It remains as the stuff around which the human paratext finds its shape. It remains as memory and as potential. Formed in this way, the Word, indistinguishable from the void except by the contours of the human paratext, denies certain kind of readings and demands others. It is no longer susceptible to what religious fundamentalists might call a literal reading, or to a reading that seeks to mobilize the text in support of some specific moral or political position. Instead, Robinson's intervention demands that the Word be read in terms of the space that it occupies, in terms of the human structures that condition its appearance, in terms of the essential unreadability of any text that might claim to be the Word. Religious experience is stereotypically about being open to the divine. But in order to approach the divine, we still need some kind of system. It still needs to be structured in a way. This unreadable and unknowable Word invites the reader not into the task of comprehension but into the space of reflection, not into an absolute void, but into the human attempt to allow the divine Word to appear. The invitation is not to understand a text, but to meditate on the spaces that are its conditions of possibility, to reflect on the human forms that provide the contours for the Word.

Jeremy Luke Hill is the publisher at Gordon Hill Press, a literary press based in Guelph, Ontario. He has written a collection of poetry, short prose, and photography called Island Pieces, and four chapbooks of poetry – Poetry of Thought, CanCon, Trumped, and These My Streets. He also writes a semi-regular column on chapbooks for The Town Crier. His writing has appeared in ARC Poetry, The Bull Calf, CNQ, CV2, EVENT Magazine, Filling Station, Free Fall, The Goose, HA&L, The Maynard, paperplates, The Puritan, Queen Mob’s Tea House, The Rusty Toque, The Town Crier, and The Windsor Review.

|