|

"Be who you are, even if it kills you"

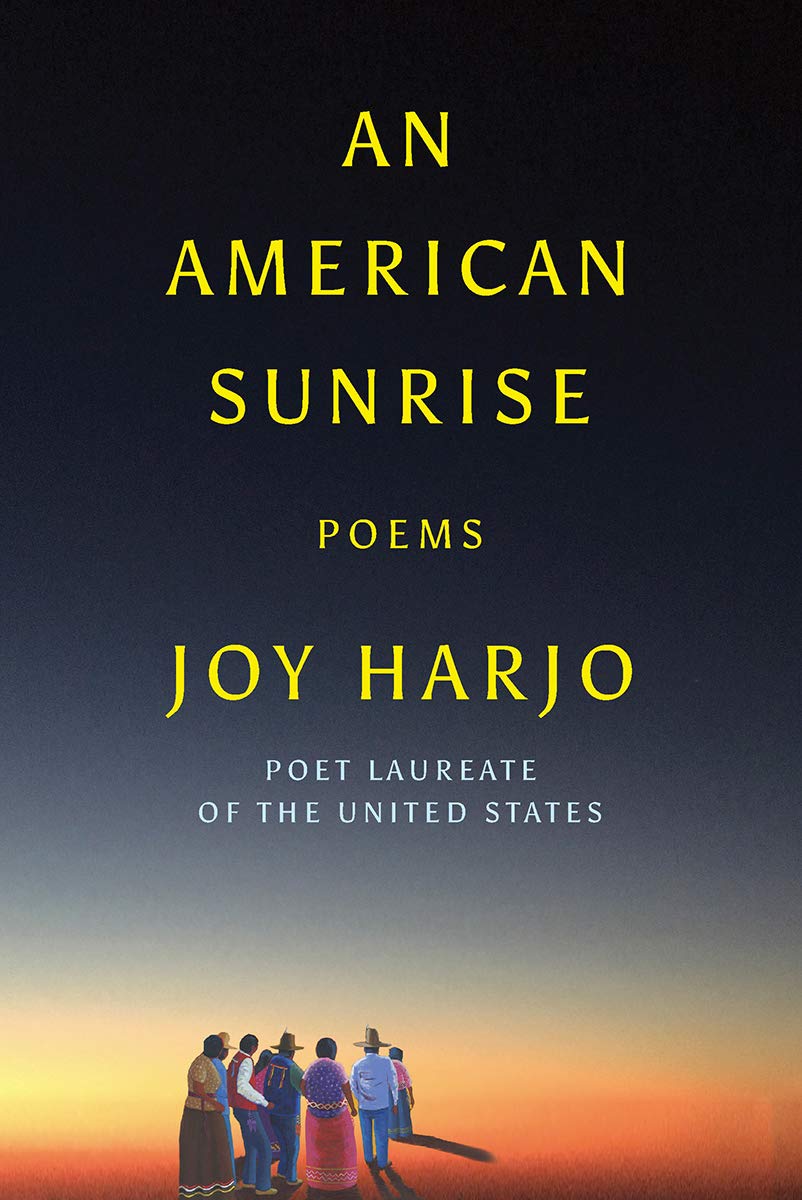

Joy Harjo A multiple award-winning poet and US poet laureate since June 2019, Joy Harjo has developed her career over more than five decades. Her first chapbook, The Last Song, was published in 1975 and was followed by her first collection, What Moon Drove Me To This? (1980). She has published nine poetry collections, two memoirs, an essay collection and a children’s book. She belongs to the Muskogee tribe, Creek Nation, and her work is centred on a search for freedom and for identity that is deeply rooted in the First Nations’ traditions, myths and legends. These myths, which are transmitted through oral storytelling, are the source of wisdom and belief that shape and underlie her narratives. Her writings also explore and express the connection with nature that Indigenous peoples have always nurtured. This concept implies a spiritual and physical involvement where human beings are strictly connected with natural elements, such as animals, rocks, rivers, plants, the earth and the sky. All these elements are linked in a relationship of mutual respect and reciprocal consideration. Harjo is also a saxophonist and vocalist and she plays the flute as well; she teaches creative writing too, mingling music with poetry in her readings. Her band, Poetic Justice, tours with Arrow Dynamics, with whom she has released four albums of music.

Her commitment to exposing and exploring the hardships and persecutions Indigenous peoples suffered after the arrival of Europeans develops at a historical, political and social level in her work. The search for social justice is constantly contradicted by past and present events that threaten the survival of Indigenous people to the point of extinction. Writing is a way to remember and therefore to survive, to give a voice to marginalised people. In her work there is a wider need for social justice that involves not only discriminated groups such as Indigenous people and Black people but also women, in a feminist perspective. Writing poetry is therefore a way to resist and oppose the mainstream mentality that tries to homogenise and silence diversity. Resilience and survival are keywords in Harjo’s poetry, and her journey points to a search for wholeness through fragmentation and healing. Beauty is embedded in this world as well in a harmonious vision where fair and foul coexist and are acknowledged as such:

In this perspective, compassion alternates with anger in a hopeful view that aims at renewal but does not exclude abuse. Her vision is powerful and humble at the same time; she is aware of the temporary quality of our knowledge, but her wise view is also timeless and open to further explorations. The spiritual and physical or contingent sides therefore merge and interact in this vision. Eventually there is acceptance of the hardships and sufferance that arise from grief and the memory of the genocide against the Native peoples. Their exile and displacement are tied to the ancestors, whose lives and stories are always present and need to be recollected. The ancestors and their stories are therefore a source of survival that guarantees the transmission of Indigenous culture from one generation to the next. Thus, she wishes to affirm and reiterate the importance of Indigenous culture, its contribution to the culture of the countries Indigenous peoples inhabit, and the fact that they are still alive despite having been threatened to near extinction. There used to be a risk of disappearing because of starvation, for example this was one of the consequences of exile during the long march from Alabama to Oklahoma, when thousands of people died; the menace of cultural effacement can also destroy communities. Even today, Indigenous peoples are not a visible part of society. However, they are resilient and maintain their traditions, which in Harjo’s poems develop in a spiritual awakening and in activism:

Hence, Harjo’s stories draw from Indigenous peoples’ myths and folklore, her ancestors, historical events and also from her personal experiences, which involve both individual happenings and visionary or spiritual occurrences. They are a celebration of Native cultural traditions that are looked at through the lens of past and present hardships and that allow a comprehensive complex view which is seemingly contradictory at times but always incisive and proud of their legacy. This attitude culminates in a prayer for the enemies who can become friends and, despite their cruelty, share their humanity with their victims.

Human weakness as well as the violence and beauty of our world are therefore acknowledged as part of the reality in which we live in a cycle of life and death, where survival is not just a physical matter but implies transcendence too. The cruelty of the white settlers, especially during the 19th century, is also linked in this collection to the present situation of migrants, who cross borders looking for a better life. Displacement and exile are therefore recurring situations in human history that characterise and shape who we are. Remembering the past through tribal and personal memories is not only a way to keep traditions alive and shape identity but also a way to strengthen beliefs and confirm the presence and voice of the poet’s people. This concept is often expressed in the form of repetitions that emphasise and reinforce concepts and keywords, developing new meanings. The dots at the beginning of some of the poems in place of a title express openness to the reader’s interpretation as well. Therefore, writing becomes a source of belief, a new beginning where personal and universal traumas are in part overcome. This hopeful and compassionate vision springs from vulnerability and heals, restoring what has been lost and leading towards a way home despite the darkness that surrounds First Nations’ history. The dialogue with the ancestors never breaks off – her grandfather Monahwee is a recurring figure – and is a connection that does not stop with death but expands even more. In this ‘trail of tears’ Harjo traces all these connections in a vision of a sun that rises but never sets; it mends what is broken and has been destroyed within us and others. The ‘circle of destruction’ becomes ‘the circle of creation’ in a poetic view where First Nations peoples ‘are still America.’ Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She obtained her Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing with Merit at Lancaster University in October 2012. Her pamphlet Negotiating Caponata was recently published by Dempsey & Windle (2020); she has also self-published a poetry pamphlet, A Winding Road (2011). She has published her work in various anthologies and magazines, and she has recently completed a PhD on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading. In 2016, she and Keith Lander won first prize in the Dryden Translation Competition with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems. She writes in English as a second language.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us