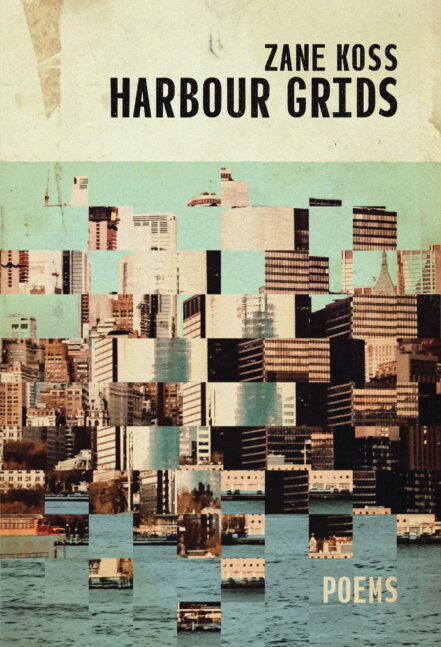

Harbour Grids,

|

|

This—poem? book? ensemble?—by Zane Koss is a sequence of grids. Four rows by four columns of the letter s, forming an evenly spaced square within the usual margins of a book. On most pages, only a few words hang on to an internal s. These words overlay the regularity, the silence of the sequence. The way words arrive is comparable to sounds arising, noises emerging, objects moving across the field of vision, against repetitive elements. Waves breaking, roofs laid out, buildings repeating their square elements.

Koss references Sunset Park once and mentions it directly in the acknowledgments. This Brooklyn neighbourhood, which boasts a view of the bay and a harbour on the bay, is the setting for these grids. The visual and sound grid is a medium for what is sudden as much as for what also regularly appears – birds and vehicles, for the most part. The prevalence of soft and hard s’s makes the whole at once obsessively consonant and occasionally broken as sh’s and sw’s just slightly interrupt the flow, a modulation of the repetition. The whole, read in one sitting, gives an impression of calm and weightlessness, a selflessness through abandon to the solidity, to the reliability of the grid. But the words hanging on by their s’s on one grid are not always coherent—any more than objects in a field of vision. We get incomplete images, the opposite of exhaustive description, and something else than minimalism. With his grids, Zane Koss offers an original form that allows for a meditative reading (and, I would assume, writing), similar to the haiku, but without its unity. Such a form allows both writer and reader to let their perceptions and verbal questions be, to notice them, to make note of them. Part I of the book offers straightforward images related to the harbour. Fog, water, ships, soil appear in variations. The agency is within the surroundings, perception an imperfect and tentative recording: “gazing, guessing // no sense // of this space / as worked” (30); “the visible // partially observed // distorts.” (32) The observer, active in their interrogation of the surroundings, shifts their attention between layers of depth, from surface to element to cosmos. This focus on the sensory continues, more explicitly, in the second part of the book, where observation gives way to bodily movement through the neighbourhood. Here there are people rather than masses of materials, the vehicles are inhabited, there are birds. New difficulties arise, as the observer is already caught within communication: “could speak // and answer / in gestures // neither of us // understand each other’s.” (58) More grids continue the previous ones – in one instance, music from a moving vehicle is introduced on the left page and “suffuses // the street” (63) on the right page, the car’s movement uniting the two grids. While Part II of the book show Part one’s observer return to an engaged involvement with their surroundings, Part III expands this involvement and questioning to history. It is fitting then that Spanish is introduced in Part II and continues to be present in Part III alongside a few words in Indigenous languages. Here a few grids are translingual, although no one speaks the words, which rather seem to occur to the speaker in isolation. Settlement, theft of land, ecocide, immigration enforcement appear between the speaker’s clearer presence, their surprises, their thoughts. Distance is maintained, without direct interaction, an indication of co-habitation of the same neighbourhood, of a life on the same land, but not of coexistence. There is only an abstract co-presence, in a space created through abstraction by the history and layout of the city: “distance // squared the blocks // to be sold as // abstract space.” (83) We begin to get a sense of an organization of reality, of obstructions, and of an experience of the limits of the position of the speaker and of his grids. The last, fourth, part, instead of taking us toward others as the movement of the three previous sections might have suggested, brings us back to the speaker, this time to their inner life. “I wish to contain, // // to be enclosed / by otherness, // saturated,” (118) we read, the position of subject being at once too much and insufficient to be a being of pure sensory matter. Koss develops this internal play of desire and impossibility of selflessness to the point of understanding and perceiving relationality—but not of living it. Relationality is named, but is volatized by this return to the self. The isolation of the speaker is not so much to be criticized as it is to be surpassed. After all, states and cities have been built to enforce segregation, to allow for the ongoing genocide of Indigenous peoples and the exclusion of migrant people—to allow for the appropriation of land and labour all the while forbidding or foreclosing the possibility of mingling, of becoming related and so accountable to one another. Discovering and naming this isolation and segregation, giving them to the readers so they may also perceive it, is already a task in itself. Throughout Harbour Grids, Koss lets the reader feel a sense of selflessness as an effect of the strength of the grids and its mesh, its open space for any possible apparition. This sense, diffuse through the form of the poem(s) appears explicitly toward the end of the book, an explicitation that defeats it by naming its impossibility, by pointing out its refusal of reality. I wonder then whether there is a follow-up to this book, new grids, with other letters, less slippery perhaps, allowing for the relations that cannot be seen or placed on grids, but can move through them, especially with a sense of depth. Jérôme Melançon writes, teaches, and lives in oskana kâ-asastêki / Regina, SK. His most recent poetry collection is En d’sous d’la langue (Prise de parole, 2021). He is also the author of a bilingual chapbook with above/ground press, Coup (2020), and of two books of poetry with Éditions des Plaines, one book of political philosophy, La politique dans l’adversité (Metispresses, 2018), as well as articles on political movements and dissent. He’s on Twitter and Instagram at @lethejerome and sometimes there’s poetry happening on the latter.

|