3 Words,

Reviewed by Terry Trowbridge

|

|

Pandemics give us a lot of time to root through our bookshelves. Therein we rediscover chapbooks and zines. Some were bought in handfuls from zine fairs and book fairs. They contain loose stickers and vendor cards, receipts, pocket lint. Others were bought at poetry readings. They are signed by the authors or illustrators, personalized; maybe they are dated. After all, a chapbook bought from the writer might pay them more than royalties from a softcover book bought online. Buying a chapbook is worth a personalized message. That kind of remuneration and reciprocation was all that we expected.

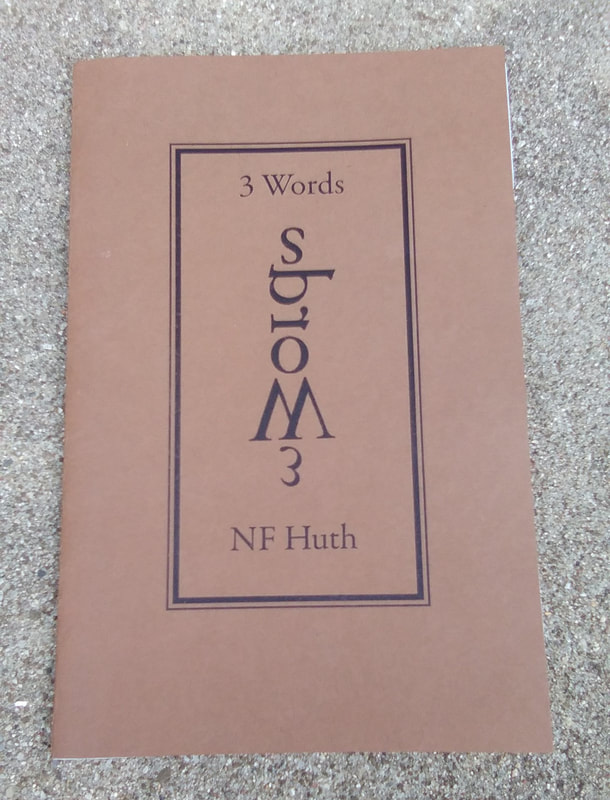

Before the pandemic, chapbooks and zines were momentary pleasures. Half of the chapbooks we brought home were read on the streetcar ride home that very night. Yet they still add to the character of our bookshelves. As bibliophiles they strike tiny flickers of subversive colour between the ordinary walls of entitled spines. Our chapbooks are little flags that signal to other bibliophiles, infovores, and bibliographers, that we are a certain kind of collector. A little more struck by magpie spirits, we stuff the crevices of our nests. A little less careful, we welcome unfinished versions of what might one day become books or might one day be rejected by trade paper editors. And we who collect chapbooks and zines make no assumptions about self-publishers, want students and teenagers to be part of literary life; we are disinterested in checking the eventual republication in more traditional books. Did a chapbook get absorbed into a book-book? Then our chapbook collection is errata by the standard of other kinds of bibliophile. Bibliographers probably reject our methods as the delusions of hoarders. You people might say we are not serious about literature. You people are probably right. I don’t know what the date is that NF Huth signed my copy of 3 Words, a chapbook published in 2011 by Hamilton poet Gary Barwin’s chapbook imprint, Serif of Nottingham. I do know that the Niagara Falls publisher Jordan Fry, of Cubicle Press and Grey Borders Books, ran a poetry reading at either The Merchant Ale House or The Fine Grind Café in St. Catharines, Ontario; and that was where we met. Huth lived (and might still) in Schenectady, New York. Her appearance in St. Catharines helped to boost the city’s scrabbling for an international literary scene. Serif of Nottingham extended the reach of the QEW from Hamilton to St. Catharines to Niagara Falls to Schenectady. NF Huth was lit. 3 Words contains 8 free verse poems with strong internal assonance and consonance, but that conspicuously avoid end rhymes. Each poem is structured around repetitions at the beginning of lines, usually with the effect of forming couplets. The first poem begins by using repetition to first signal a mind that is unsatisfied, “She throws out the dishwater that is still hot.” In the second line it signals dissatisfaction with a decision that can’t be undone, or maybe self-criticism, “She throws out the dishwater that is still hot enough to use.” The third line, “She uses cold instead.” is about how the protagonist experiences the water. The fourth line, “She washes the dishes in cold water” signals resignation, trapped in her decision and refocused for it. The rest of the poem is about the protagonist’s self-awareness. In this way, 3 Words is introduced to the reader as a meditative mood. 3 Words is more formal than simply using repetition. It is a study of the broad rhetorical device repetitio (Lanham, 1991, 130), or more specifically, conduplicatio (Lanham, 39), the repetition of words in succeeding clauses. Each of the eight poems demonstrates a distinct kind of awareness that repetitio can create in a text. The poems almost all establish couplets using the rhetorical device anaphora (Lanham, 11). The prevalence of repetition in each poem builds a kind of anaphoristic surge; a surge of what Richard Lanham calls Epanaphora, “intensive anaphora” (Ibid., 66-67). The beginning of sentences repeated, along with their internal rhymes, building ideas upon ideas and ideas upon rhymes. The second poem, “When Space Is” is about a suburb called Meco. There is a real-life hamlet called Meco in the rural outskirts of Jonestown, New York, which might be the place, although verifying Meco’s existence is currently difficult. Google Maps does not readily display Meco, opting instead for the Meco Corporation headquarters in the USA, and locations in Mexico and Spain.[1] We have to settle for NF Huth’s poetic Meco as the only English-language Meco worth mentioning in the whole world. “When Space Is” repeats words, sounds, sentences structures. It is not a poem about unique features. Repetitio describes the common features of a place. It establishes the character of the town through reiterated geography, prevalent lawns and lawn chairs, powerlines, driveways. What is visible in the poem that establishes Meco is what might make Meco invisible even to Google Maps. Even the water feature, a lake, is mundane:

Which is an understandable description. The water, if it is truly an exceptional destination, is reflective and clear. If it is reflective, the lake repeats the trees (and other scenery), surrounding it. Meco is hard to see, and so is the lake.

The protagonist is presented with multiple conflicts in this poem. In the first poem, she is self-aware, in conflict with her own internalized unease. In the second poem, “She knows she is not at home in Meco./She knows she does not sit in yellow lawn chairs at home.” Even though it is obvious she resides in Meco, she feels disconnected from the repeating features of houses and their lawn furniture. Repetitio, as a rhetorical device, is used by NF Huth as a way for the protagonist to know that she is in contrast with the character of her surroundings. The third and fourth poems are about staccato rhythms. In the third poem, a thunderstorm deluges Meco: “She taps the walls as she moves through the rooms./The walls are strong and sound./Summer is all percussion and crash.” A new reflection, one made by kinetic energy instead of by light, emerges from the geography, “A curtain of rain pocks the surface of the lake,” in the sixth line, and “She sees the sky for the lake” in the twenty first line. Repetitio establishes the contrast between anthropocentric architecture that stands firm, rigid, in the weather, unlike the synergistic natural textures of the thunderstorm. In the thunderstorm, the repeating sounds and textures resound across all the media of sky, lake, trees. The fourth poem elaborates the concept of staccato experiences by transferring the protagonist’s attention to her experience of time’s periodicity. “She was having a staccato afternoon of finger taps and statements./Finger taps show the period./Finger taps dot the notes.” Note music as notation. This poem specifically opens up the reader to two analyses that are facilitated by Repetitio. One analysis is that the meditative mood of the chapbook belonged to the reader, whereas the protagonist’s mood diverged because she is anxiously self-aware and disconnected. However, the protagonist’s mood converges now with the reader’s mood. Halfway through the poem, staccato is reversed by its antithesis, “She wonders porch and lake./Some questions are legato./From the porch her questions are smooth and without end.” According to experts like Alan Watts, meditation reaches mindfulness through an experience of monotonous repetitions (Watts, 1996, 19-32, 91; 1973, 63). The protagonist’s mood becomes an experience like Zen koans, “She moves a pair of shoes from here to there./This does not answer a question./Answers to some questions must be left blank.” In the earlier poems, Repetitio represented alienated and anxiety. In the fourth poem, then meditation and mindfulness, while maintaining the anaphora structure of all eight. The second analysis is an emphasis on the entire chapbook as an experiment in repetitio in the form of NF Huth’s meditation, and the reader’s involvement in experiencing those hypnogogic rhythms and rhymes. “Each room is full of blanks./Each room fills with blanks and slashes and periods./She voices this notation.” Although the reader is blindsided by that “voice” of “notations” which amounts to a list of punctuation marks. “She measures the signs that puncture the air” ends the poem by invoking the unvocalized punctuation marks in the ethereal air. The blanks, slashes, periods, are immaterial, like time. The fourth poem is possibly the most complicated in the book. It is especially complicated since classical rhetoric based on Aristotle and Cicero renders “period” as one of the most important and heavily analyzed concepts (Lanham, 112-114). Huth herself presents augmented periodic sentences (Ibid.), throughout 3 Words that play with the ideas of a complete thought, a complete sentence, the relationships between clauses, and their elasticity or minimalism. She essentially unifies time’s periodicity with periodic sentences. That the divergent moods of the protagonist and the reader become convergent moods when Huth’s poems shift focus from terrestrial geography to ethereal weather is probably intentional. The fifth poem is about the protagonist feeling her way through her own home when she is blind. During the first four poems, the protagonist relies heavily on her sense of sight. Huth contrasts what the protagonist touches with what she sees. What she touches often results in a moment of self-doubt (as in the first poem’s hot and cold water). What she sees often alienates her (she does not belong in the scenery of Meco). In the fifth poem, Huth interiorizes the sense of alienation through blind navigation of the protagonist’s home. Repetitive touches are necessary for her to travel around corners. “She can’t see around the corner so she gathers her things…She walks around the corner with her hands full” and “She feels the pointy part. She feels the pointy part of the corner with her fingers.” The poem proceeds to describe placing objects on a chair. She must touch everything multiple times to be sure of each object’s position. Without sight, her sense of place depends on repetitive tapping, “She hears the chair call” and “Her fingers tap these.” Furthermore, the poem offers a brief sense of aphasia that comes with walking in the dark, “She wonders the names of the brush and shoes and chair” and in wondering their names, she also makes a decision to put them away, “She moves them to make them clear./She puts them into holes.” The fifth poem uses repetitio as the required actions to move blindly. Repetitio also creates space. Without remembering nouns for each object, the protagonist relies on repetitive movements to organize herself and her place. The sixth poem almost recalls the title of 3 Words with its title, “When Three Is.” The sixth poem is about counting. The first sixteen lines are about finite numbers: four or fewer. The last eight lines, though, are first about sets of things, inclusion and exclusion from what counts as counted:

So, the protagonist experiences set theory in the breach of set theory. The architecture of her home fails in the weather. The weather makes “the out and the in” immanent and important. The weather breaches the screen door and in doing that, Huth makes obvious her epanaphora. Huth’s anaphora is intensive.

In the last lines of the sixth poem:

Huth seems to be circling around the idea that counting is one and one and one and one and one and onward, finite and infinite at once. And sometimes, Huth seems to write, onward until a puddle forms and all the ones are one.

So much for discrete items. Repetitio undoes number. The seventh poem is about music and phrases. The obviousness of Repetitio and music needs no explanation nor, for that matter, literary analysis. The seventh poem also uses smell and touch to expose the protagonist to the edge of that change. “The widest smell is the air that seeps to the edges./The edges are sometimes empty./The edges are sometimes frayed.” As a person, the protagonist can experience items, like the smells of outside air, that change shape. But her experience of those phenomena make sense in the aggregate. She must repeat her experience of smelling and touching, inside and outside, weather, the indoors, in order to know that they are inconstant; in order for her to know that there are edges to metaphorically fray, and sometimes no edges at all. The eighth poem is not unlike a lesson in a textbook for drawing. “It takes both hands to show empty./Hands are brackets that hold up nothing” invokes negative and positive space. Huth elaborates on what hands can do, “Two hands can form a V./All lines begin at percussive and punctuated points.” The eighth poem is a condensed description of how formalism makes sense of line and space. Regarding drawing and negative space, a reader of the eighth poem can turn to any page in Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (Klee, 1953), and use Huth to understand that random page of Klee. For Klee, lines are repeated from an origin point, in order to construct space. Lines have periodicity and that is the quality with which they express form. That is NF Huth’s eighth poem’s insight into the use of the rhetorical repetitio. You might disagree, but those of us who collect chapbooks can do it. We can even read Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook and turn to any stanza of Huth and understand that random stanza. NF Huth works both ways regardless of the screens on our doors. Repetitio is not synonymous with counting or with listing or with repeating; but rather contains them all That is, perhaps, why a collector of ephemera amasses it in staccato sheaves between otherwise neatly aligned, legato planes of text on book spines. All those vertical, rectangular bindings and yet between them are occasional flocked zines with their flimsy folded disorder. Of course, you can ask us if we are we learning anything new by reviewing old chapbooks during the pandemic? How many times will we repeat the same motions before lockdowns end? Staring at our bookshelves, we anxious fill bibliographic gaps that had, before the pandemic, been left behind. Perhaps what we (who read chapbooks and zines) ask of you, is whether we are making up for lost opportunities, or if we are creating new opportunities by retracing our steps, submitting, reopening. [1] Wikipedia saves the day by mentioning Meco exits as part of Jonestown’s municipality but other than appearing in a list, even Wikipedia cannot be bothered to describe it. NF Huth is the de facto Meconian voice. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnstown_(town),_New_York#Communities_and_locations_in_the_town

Terry Trowbridge is a PhD candidate in Socio-Legal Studies who is spending the pandemic isolated and vaccinated as a plum farmer on the shore of Lake Ontario. His chapbook reviews have appeared in Hamilton Arts & Letters, Studies in Social Justice, and Episteme.

|