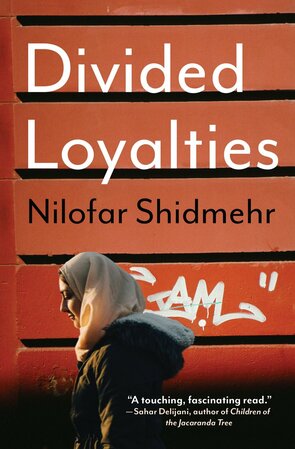

Nilofar Shidmehr’s Divided LoyaltiesReviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

Neither a camel nor a barbarian to be seen: Nilofar Shidmehr’s stories correct what Lila Azam Zanganeh identifies as “endless misconceptions about Iran, some humorous (think camels), others less so (uncouth, Indiana Jones-caliber barbarians).”*

Actually, a single camel: only one, in a proverb recited by a young girl. From a class-aware Cinderella to a self-aware mother, these stories are populated by revolutionary women. Divided Loyalties reflects decades of Iranian women’s experiences, spanning from 1978 – through and beyond the 1979 revolution – to 2008. These nine stories highlight aspects of women’s lives which are often overlooked, and they subvert traditional expectations in both small and large ways. In “Butterflies on the Bus,” readers travel with a young sister into spaces that are traditionally hidden and follow her through a series of events that redraw the lines between agency and resistance. Another writer might have written the story of her brother, but, here, he remains off-stage; instead, readers consider how women possess and wield power in positions where they could be perceived as powerless, and how their emotional state can create or abdicate a position of power. Each story challenges conventional roles of perpetrator and victim. Sometimes, the symbolism is clear, as in the sister’s story, with her name Parvaaneh (‘butterfly’). Sometimes, statements are direct, as in “Let Go of My Hair, Sir!”: “I, Sima Ghafoorzadeh, am not a victim – a ghorbaani.” Sometimes, characters outwardly challenge social norms, like Pari in “The Gordian Knot,” who contradicts a female neighbour who advises her to accept a pending marriage proposal. More often, however, there is no outward demonstration, only a silent and subversive decision. Nilofar Shidmehr dedicates this volume of stories to her daughter, Saaghar, “with new hope for unification.” Shidmehr views “Iranian women as being “at the forefront of struggle for social and legal change, individual and public freedom, and democracy.”** In their personal decision-making processes, her characters strive for self-expression that will lead to broader change. These women acknowledge their own needs and often manage to prioritize them, not only over political and religious systems, but also over the needs of friends and family. In “Divided Loyalties,” for instance, Maana has been living and working as a realtor in British Columbia, when she returns to Iran: “I’m sure if I told people that the reason for my immigration to Canada was to escape my family, no one would believe me.” Maana’s decision to live apart from her family is a quiet but revolutionary act. Even more remarkable, in “Family Reunion in the Mirror,” is Homa’s decision to divorce and emigrate to Canada, leaving her ex-husband in Iraq to raise their daughter: “The myth of what makes a good mother was made by men.” Mostly, these women experience difficulties that are expressed directly, but occasionally a figurative flourish adds to the tension, with images of repression or trapped energy, such as steam rising from hot asphalt or heat built up behind a closed apartment door that “jumps at her like an armed enemy.” Voices crackle and anger boils, but Shidmehr’s prose is clean and her language is matter-of-fact. Some structural decisions do, however, add a degree of complexity to the storytelling. In one story, there is a clock on a wall, which outwardly measures time as it moves toward a scheduled event, while the action in the story circles between memories and impossible futures as time passes. In another instance, a character waits in line for a transaction and experiences a small epiphany before the transaction concludes. In another, a character listens to a message left via telephone and makes a decision while the recording plays. “Butterflies on the Bus” begins and ends with a bus ride, and, in “Yellow Light,” a character reaches a conclusion while crossing an intersection and moving through a streetscape. These measured timelines allow the author to control the pace at which readers receive information and, thus, their engagement with the stories. In her 2008 memoir, Things I've Been Silent About, Azar Nafisi (best known for her memoir Reading Lolita in Tehran, which described her work with female students who persisted in studying Western classics forbidden under growing Islamic fundamentalist rule) writes about the things in Iran that her parents concealed, even from their children: |