Interview with Tom CullInterview conducted by Kevin Heslop

This interview took place on July 13, 2018. It has been edited for length and clarity.

|

|

Kevin Heslop: So, let’s begin by acknowledging that the land on which we’re speaking is the traditional territory of the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, Wendat, Attawandaron, and Lenape Indigenous peoples. This territory is covered by the Upper Canada Treaties, including Treaty 6, the London Township Treaty.

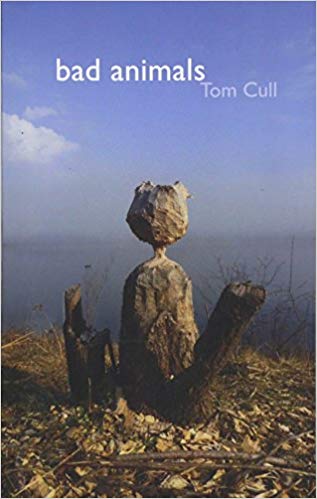

The opening lines of the first poem in Bad Animals are, “I’ve waded below the Hunt Weir / where the dam drops the river.” They seem to explain that the book will, in part, go on to identify human abnegation of responsibility for the world around us: we’ve “dropped the river” by means of the dam. Laurie Graham has it that the book “sings a natural world rendered absurd by human hands.” Tom Cull: Yeah. Yeah.

So, what in Nick Cote’s photograph “City Parks” were you responding to with your opening poem “After Rivers”; why did this feel to you to be the image of the book’s beginning; and what tone or tones did you want to activate with this opening poem?

So, this came out of a course I was teaching at Western, Writing 1000, the Writer’s Studio, and the writer-in-residence that year was Margaret Christakos, and she was doing some work around ekphrastics, and I thought: OK, this is a perfect opportunity to get my students involved. And I was teaching this course and she said do you want to get your students involved in this? Which just involved taking them to Art Lab? Yeah. And it was the collective show of the fourth-year students––their major works. Right. So, I brought my students, and Margaret invited other folks to come and we all kind of chose a painting or sculpture or something. Then, we had a night when we invited people and walked to the place where their art piece was hanging and then they recited their poems. It was just a great event. So, I really responded to Nick’s triptych––it’s a triptych of three photos of the river, an almost panoramic view in black and white, and they’re great because there’s no intent to try and capture pristine, untouched nature. Right. One of them is the photo of the construction on the west London dyke. That west London dyke was put there historically because of massive floods in 1937 that had Blackfriars underwater, right? Yeah. So there’s massive construction. I think there’s even Portapotties in the background. So I love the image of the Portapotties beside the river because I think about sewage and how much sewage goes into the river every year due to city infrastructure. It’s a portrayal of the river that I really responded to, because there’s a whole tradition in poetry and nature writing that’s sort of responding to a romantic, uh–– Pure nature. Pure nature, untouched, all of those kinds of things. Because where is it pristine? Where is it pristine? And nature’s always filtered through our cultural––nature is a discourse. Yeah. But, the other thing I really liked is that this photo of the Thames River, or Eshkani-ziibi––if I could puncture that gallery wall, I would have been looking at the river. Right? ‘Cause Western is bisected by the river––it goes right behind the gallery––so I liked that idea of, “This is not a river.” That line which is obviously an allusion to that line, “This is not a pipe.” Is it Magritte? Can’t say. Right, that famous painting of a pipe–– Oh, yeah, yeah yeah. Magritte. It’s a painting of a pipe; it’s not a pipe. It says, “This is not a pipe.” Which is about representation and all those kinds of things. And so I liked the representation of the river and the river being right there. And, you know, the river is contained within this photograph, or contained in the poem, but also this river that in this photograph is being contained by the west London dyke, and being held in. And so all these ideas were percolating, and then, also, the river is, for me––personally it’s kind of like a––I don’t know how to describe it, but I spend a lot of time at the river. I pay attention to the river with my environmental groups–– You’re invested in the river. It’s part of–– Yeah, so we spend––the river is the source, in a lot of ways. Our river clean-up group, we’re doing a clean-up–– Tomorrow. Tomorrow morning. So, I’m constantly at the river, thinking about the river. My partner Miriam, and our son, our relationship evolved at the river, so–– You started the Thames River Rally together, yeah? Yeah, we started the river rally together. At our first river rally, Emmet was about a year-and-a-half old, and I had just met them a couple months before. And so that’s kind of the beginning of our story as a family, is also about the river, and about London, and this journey we’ve been on. And anyway, all of this is bubbling along in “After Rivers” as well as all the ecological stuff––abandoned nature, dollar-store pottage, the current state of this very embattled river, as well as these tangled narratives, right? So, since you brought up the question of family and your personal relation to the river and how your relationships with your partner Miriam and son Emmet are sort of embedded, in a way, with your experience of the river––you have the poem, “At the Pinery”, which conveys the beautiful line “This is where I tell you about the boy:” Yeah. |