Interview with Jaclyn DesforgesInterviewed by David Ly

|

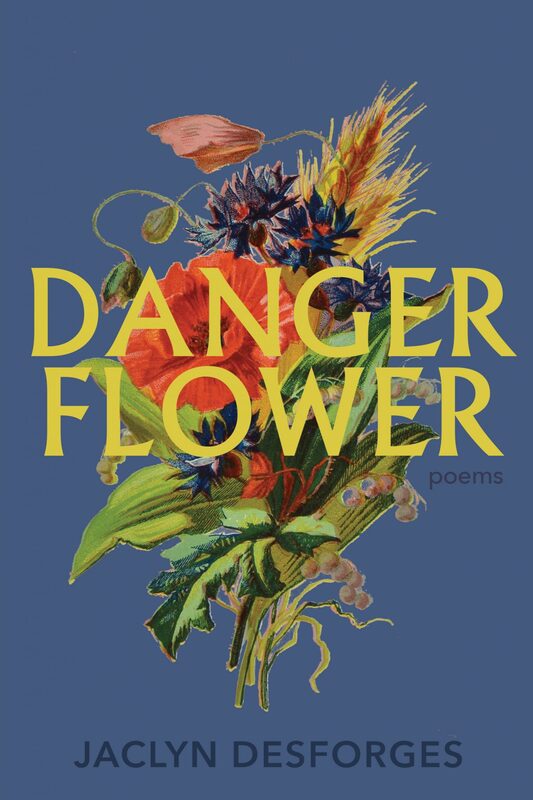

Navigating gender roles, sexual indiscretions, episodic depression, and mothering, Jaclyn Desforges’ poetry collection Danger Flower is a fantastic debut that delivers unexpected and delightful poems. What follows is an interview between Jaclyn and David Ly as they discuss the importance of the unconscious, how fairytales inspire Jaclyn’s writing, and how her chapbook grew into a full-length book.

Jaclyn Desforges is the author of a poetry collection, Danger Flower (Palimpsest Press, 2021) and a picture book, Why Are You So Quiet? (Annick Press, 2020). Jaclyn is the winner of the 2018 RBC/PEN Canada New Voices award, two Short Works Prizes, and a 2020 Hamilton Emerging Artist Award for Writing. She is the Poetry Review Editor at the Hamilton Review of Books, and her writing has been featured in literary magazines across Canada. She is an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia’s School of Creative Writing.

David Ly: I love how your collection opens with “Reverse-maid,” where, during a baby’s baptism, she turns into a reverse mermaid: with the head of a fish while the rest of her is human. It’s quite a surprising and memorable image with which to start the book. What made you decide to have this poem first and where did the idea for it come from?

Jaclyn Desforges: By putting it first I think I wanted to say: this is going to be a weird book! This isn’t going to be what you might expect. I wanted the poetic world I was building to feel a little bit unnerving right away. And I think that poem is really about rebirth and transformation, which are key elements of the collection. As to where that poem came from: I have a thing about mermaids—my website describes me as “poet, teacher, secret mermaid.” I have a mermaid tattoo on my right calf, and I’m planning to get a reverse mermaid on my left calf. I’m not sure why I’m obsessed with mermaids, reversed or otherwise. But all my poems begin really deep down, in my subconscious, and there are definitely mermaids swimming around in there. I think it maybe has something to do with how I see myself—interacting with the humans on land sometimes, but for the most part, spending my time navigating this other world, this imaginary one. It’s sort of the job description of a poet. DL: Navigating imaginary worlds is something I can definitely relate to in terms of writing poetry. Which brings me to the next question: I love the fairy tale-esque narratives you explore in your poems—especially in “Survival Strategies,” where it appears readers are introduced to a cast of characters who could have nuanced backstories. Do you feel fairy tales play a role in your writing, and if so, how? JD: I love fairy tales. Especially the very old ones where almost everybody dies. They’re often representations of the darkest elements of humanity and they also teach us—symbolically, psychologically at least—how to survive. They creep me out and I like that feeling. I was reading a lot of old fairy tales at the time I was writing Danger Flower, so I’m not surprised some of the poems have been infused with that energy. My favourite fairy tale is Thumbelina—it’s the story I most connected with as a kid. And like Danger Flower, it’s filled with rebirth and transformation. Fairy tales, dreams, and the unconscious mind all play a really important role in my writing because that’s where I get my material from. I find my unconscious to be a lot more interesting than my conscious mind. My conscious mind is usually fretting over something and distracted. DL: Well it definitely helped you to tap into your unconscious for this book—which, by the way, is so beautifully titled. I love how suggestive and intriguing it is. Even the four sections of your book are titled after flowers. Where did the idea of using flowers come from, and did you settle on the collection’s title early on in its creation? JD: The working title of this book was Herbal Remedies For The End of the World, which I came up with on a writing retreat in February of 2020. That ended up feeling way too on-the-nose when the pandemic hit. I still wanted something to do with plants—so much of this collection is about death and rebirth and regeneration, which plants embody just by being themselves. And I wanted reading the book to feel like walking through a spooky, overgrown garden. My (our!) editor Jim Johnstone ended up suggesting Danger Flower for the title—it’s also the title of one of the poems. He’s a fantastic title picker. He also chose Hello Nice Man for my chapbook, which came out in 2019. DL: Which is one of my favourite chapbooks, by the way. It’s nice to see that a few poems from that chapbook make it into Danger Flower, such as “Home Address” and “It’s the Small Things That Save Us.” In what ways did you want to explore poetry that you didn’t do in Hello Nice Man? JD: When I was writing poetry early on, it felt like a process of translation; I would have a thought or an idea, and then I would feel the need to translate that thought or idea into a kind of poem language that was different from my own voice. I had to wrestle with those early poems, I had to figure out how to say what I was trying to say. But part way into writing Danger Flower, I realized that my voice had its own kind of music. I learned that I could be looser in my writing, that I could begin to trust the natural musicality of my own voice, my own thoughts. And I could begin to trust the images that were coming up from my unconscious, even if they didn’t make sense right away. I no longer needed to be in control of the poems in the same way. So you’ll see that some of the poems in Danger Flower are a bit looser, a bit freer, and those poems are my favourites. I think early on, I was trying to write things that other people, people smarter and more worldly than me, would interpret as poems. I think that once I got free of that idea, my work got a lot stronger. So that’s been a major shift in my poetic practice. These days, I’m working on my short story collection, and I can see the same thoughts spinning around in my head—is this a story? Does this count as a story? So I think it’s all part of the process. It’s hard to shake off that uncertainty, that imposter syndrome, especially when working in a new genre. DL: A few favourite poems of mine in Danger Flower are “I’d Rather be Drab,” “Pillow Talk,” and “Survival Strategies”—they are deceptively simple in their construction, yet speak to your book’s themes on such intimate levels. What are some of the poems you absolutely had to have in this collection? JD: There is a suite of poems I wrote during a very difficult depression. Those poems are “Birth,” “Episodic Depression,” “Ventilation,” and “Trauma Panorama.” They’re strange, they’re not logical, they’re dreamlike, and they’re my favourite poems from this collection. I think they express the illogic of the experience of depression, that kind of upside-downness that happens when your life looks fine on the outside but feels immensely painful on the inside. “Episodic Depression” expresses that feeling through the disjointed lines and imagery—time doesn’t operate normally anymore when you’re depressed. The things that used to make you happy are still there but they’re empty, like cicada shells at the end of summer. It’s a terrible feeling. It feels weird to treasure these poems so deeply, the ones I wrote when I was looking into that void. But I do. I never want to go back there, but I’m so happy to have these relics from that time. DL: I’m glad you were able to create these relics for the book too. Now that it’s out in the world, what are you hoping readers take away from Danger Flower? JD: I hope they love it! I hope they enjoy reading it. I hope they read it out loud and keep thinking about it for a long time after and talk about it with people who also read it. That would be a dream. It’s always hard to tell what will resonate most with readers—I guess my truest hope is that readers take something from this book that I hadn’t thought of, consciously. I made these poems, but I only have my own perspective—I think there are meanings inside each of them that I don’t fully understand yet. I can’t wait to hear what other people think. Photo by Erin Flegg Photography

David Ly is the author of Mythical Man, which was shortlisted for a 2021 ReLit Poetry Award. David also wrote the chapbook Stubble Burn. His sophomore poetry collection, Dream of Me as Water, is forthcoming with Palimpsest Press/Anstruther Books in 2022. David is the Poetry Editor of This Magazine, part of the Anstruther Press Editorial Collective, and a Poetry Manuscript Consultant at SFU’s The Writers’ Studio.

|