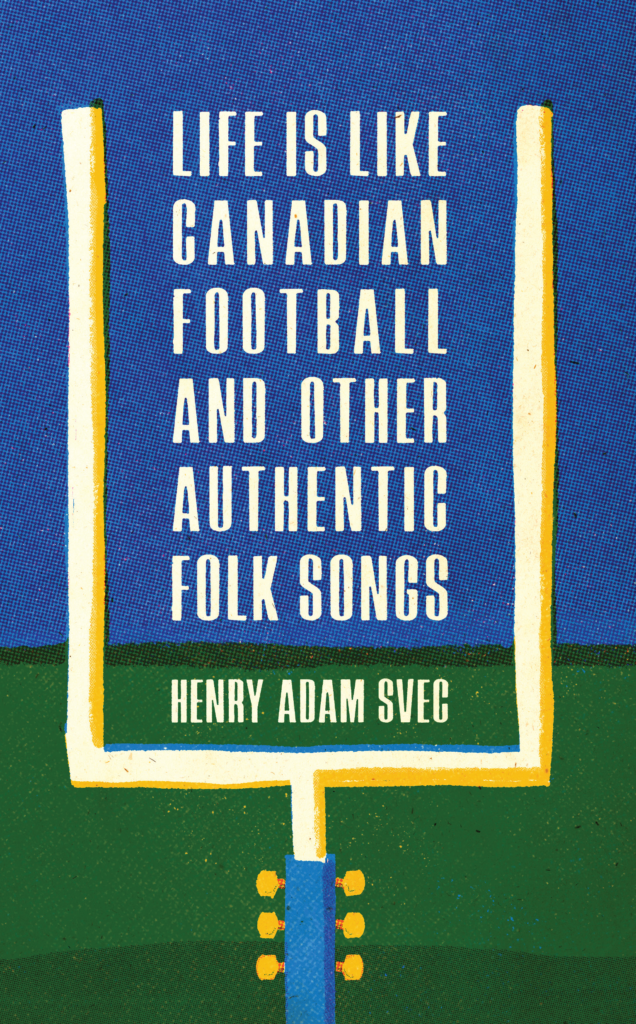

Life is Like Canadian Football and Other

Reviewed by Aaron Scneider

|

|

Henry Adam Svec’s debut “novel” is one of the rare books that merits the quotation marks around novel. Life is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Folk Songs tracks the career of an itinerant researcher and folk song collector whose journey begins, if it has a beginning, with the discovery of a collection of recordings of Canadian folk songs from the 1970s in the basement of Library and Archives Canada, and follows him through “an episodically structured Volkskunderoman, across which the development of [his] philosophy of song collection, and the development of [his] self, are chronicled.” The book is a wild curatorial picaresque with stop-offs in the academy, a basement apartment in London Ontario, a music festival, and to write an AI that itself writes folk songs. The chapters are intercut with folk songs whose lyrics run the gamut from kitschy Canadiana to one written by the AI that ends in handful of unsingable Xs arranged in such a way as to suggests several different shapes without settling on a definite one and a song that has been passed through Google translate several times to avoid copyright infringement. The chapters themselves are larded with academic jargon and spend as much time digressing on the nature of collection, folk songs, culture, etc. as they do delivering conventional plot. The text of both the chapters, and the songs bristles with footnotes that are sometimes confessional in nature, but more often academic, and the bibliography at the end of the book is as important as the acknowledgements section it follows. At this point, I suspect that you have made a decision about the book: it’s either a book you want to read, or one that you don’t. And I also suspect that most people will decide that they don’t want to read this book. It is not a book that is easy to describe in a way that makes it accessible, but its strangeness, its oddity, its refusal to fit easily into any category are exactly what make Life is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Fold Songs such a delightfully off-kilter and entirely unique reading experience, and one that more readers should be open to.

As well as inhabiting a grey area between multiple genres, the book exists in an indeterminate space between documentary fact and the fabrications of fiction. The songs are variably attributed to invented sources and real, existing musicians. For example, the song “Maggie Howie” is noted as being written by Olenka Krakus, the lead for the band Olenka and the Autumn Lovers, and, for close to a decade, a very real and tangible member of the London, Ontario music scene. Fittingly, the book further notes that the song was recorded in London, Ontario. But this is more than a weaving together out of which it is possible to tease distinct strands of truth and fabrication. Staunton R. Livingston, the collector who recorded the songs the narrator finds in the archives, is a fiction, but the Livingston AI is a very real program created by Svec and a Czech programmer—a little Googling will take you to songs it has produced on Discogs or bandcamp. And, then, consider this sentence: Like a spiritualist séance facilitator or alchemical spinner of gold, Livingston produced recordings of folk songs with his magnetic tape machine at the same time that he erased himself, not as a creative being, but rather as an individual proprietor of creativity, from the equation. The sentence is footnoted with several sentences from Henry Adam Svec’s “Dissertation Proposal Defense” from the University of Western Ontario where Svec did, indeed, do a PhD., whose proposal he presumably defended. The fictional collector erases himself. The fictionality of the collector is erased by the reality of the real Svec. The real Svec superimposes himself over the fictional narrator only to simultaneously have his reality called into question by the inclusion of the fictional (but perhaps slightly more real because of this inclusion) Livingston in his dissertation proposal. Or, really, all of the above, and more, within the complex interplay of invention, erasure and reinvention that animates not only this sentence, but the book as a whole.

One of the specifc and very real pleasures of Life is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Folk Songs is how firmly and recognizably it is grounded in London, Ontario, where the narrator does his graduate work. He lives in a basement apartment in a building that anyone who has spent time in the city will recognize. He is supervised by a professor who is similarly and uncomfortably recognizable to anyone familiar with the university. London, as many long-time residents like to observe, was a vibrant cultural centre in the sixties and seventies, but fell fallow for close to forty years during which the best that the city could boast was the clumsy propaganda that Penn Kemp, the city’s first poet laureate, tries to pass off as poetry. There has recently been a creative resurgence in the region, with genuinely strong books from the likes of David White, Sile Englert, and Kevin Heslop. Svec’s book should be read alongside them as a contribution to a re-emergent literary scene. As I began by observing, this might not, at first glance, look like a book for everyone. With its tongue firmly in its cheek and its feet just as firmly planted in the academy, it might look like the sort of super erudite post-modern serious-unseriousness that appeals to a very limited subset of readers—think, the people who finished David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, and then immediately followed that up with his history of infinity. I say “might,” and mean “could,” but really mean “shouldn’t.” Canadian reading culture remains decidedly middle brow, characterized by an understanding of books as readily consumable products (short stories that stay assiduously within the narrow limits of domestic realism and novels still largely defined by the long echo of lyrical realism) whose purpose is to reinforce their reader’s sense of self rather than to test, stretch, or unsettle it. It is an approach to reading that can be (and often is) inimical to books that don’t fit quite as easily as others into the tidy slots of literary commodity culture. And literary commodity culture is decidedly a culture of consumption rather than of critique, so books that don’t fit are ignored rather than addressed. This is the first review of Life is Like Canadian Football and Other Authentic Folk Songs to come out since the book was published about six months ago. The book ends on the hopeful note that reader will, themselves, pick up and run with the ball of folk song collecting, continuing and expanding the narrator’s project into a “listening together in the always and evermore abundant fields of folk song,” and I want to end this review on a similar note: this is a clever, delightful, perplexing (in the best way) and wholly original “novel.” It is my hope that a few readers of this review will pick up and run with the ball of this book, passing it on, recommending it to friends, carrying it in whatever way they can to an audience who might not know where to place it, but will, if they let themselves, definitely enjoy reading it. Aaron Schneider is a Founding Editor at The /tƐmz/ Review. His stories have appeared/are forthcoming in The Danforth Review, Filling Station, The Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Pro-Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, BULL, Long Con, The Malahat Review and The Windsor Review. His stories have been nominated for The Journey Prize and The Pushcart Prize. His novella, Grass-Fed, was published by Quattro Books in the fall of 2018. His collection of experimental short fiction, What We Think We Know (Gordon Hill Press) was published in the fall of 2021, and his novel, The Supply Chain (Crowsnest Books), is forthcoming in Spring 2022.

|