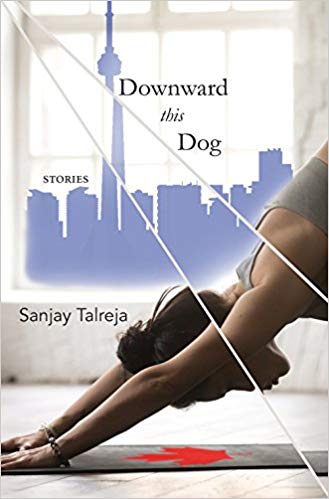

Sanjay Talreja's Downward This Dog!Reviewed by Amy Mitchell

|

|

Sanjay Talreja’s Downward This Dog! is a wonderful collection of loosely-linked stories about immigrants from the subcontinent and their experiences in Toronto. These stories are expansive and perceptive; they are recognizably grounded in the world we live in right now, and all of the characters, even minor ones, are alive. The collection is, in turns, fun, angry, gentle, and complicated, and Talreja isn’t afraid to examine difficult issues, such as the impact of 9/11 on non-white communities and on the radicalization of individuals living in North America. Downward This Dog! provides the reader with both a great read and a lot of insightful material to reflect on afterwards. I very highly recommend it.

One tendency that I dislike in stories is authors’ decisions to hold their narratives at one remove from the material problems of life in the twenty-first century. The day-to-day challenges and complexities that we all face or at least know of get elided in favor of simply focusing on characterization and plot, with the result that the story could take place in a somewhat-detached (although usually first-world) Anywhere. I was delighted to see that Talreja very adamantly does not do this. Even if they are not directly affected by these issues (and they often are), his characters are very aware of problems such as the miseries of contract-based work for young adults, the failings in Canada’s vision of itself as truly multicultural, the lack of support that immigrants receive once they arrive, and the exploitation of international students. Consider the statistics that Baby, a young graduate with a Masters in Economics from the University of Toronto (“main campus,” as her proud father likes to point out), knows about immigrants in Canada: |