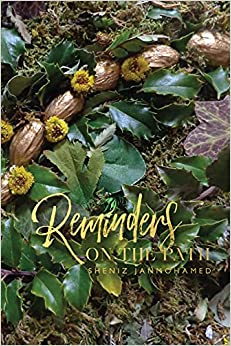

Reminders on the Path

|

|

In Sheniz Janmohamed’s third poetry collection Reminders on the Path, the narrator is a tender guide through the obstacles and hurdles life brings. The poems pass through current and ancestral homes, speak to ancestors who are both blood-related and chosen, and even morph the narrator from being on the path to being the path. By the end of the collection, the speaker reaches the end of the journey they have undertaken. This end is not a final end, but rather a pause in a journey that will continue beyond the pages of the book. Janmohamed writes in free verse and ghazals, and each poem reflects and engages with Sufi poetic traditions.

The collection opens with an author’s note about Janmohamed’s ancestry, giving context to the people and places who make up her path. She writes: “this collection of poems honours this sense of unknowing and seeks to explore the relationship between the journeys of my ancestors and my own journey as a settler and third culture kid” (x). Interspersed throughout the book’s four sections are illustrations by Janmohamed that depict doorways and stone swirls, which act as visual motifs for where the narrator is on the path at any given moment. The first section “Inheritances” opens with a poem titled “Ancestors” that sets the tone for the path’s origins and the direction in which the path leads. “I am clay / moulding itself over and / over again / the folds of decades / and decades / behind me / before me / within me” (6-7), writes Janmohamed. Despite the path being about moving forward through life, the narrator is formed by ancestors, and is always accompanied by ancestors. In “Salt,” Janmohamed echoes this sentiment of accompaniment as she writes: “What use is a map? // your heartbeat is the compass” (10). The active act of reaching out to ancestors is necessary in the aftermath of colonial rupture and the double and triple displacements that follow it. The poems are full of a desire to remember, and this is where some of the guiding elements of Jamohamed’s poetics shine brightest. She crafts lines that come across as affirmative for those grappling with ancestries that have been partially lost because of colonialism. For example, in “Blood Memory,” she writes:

History is collected in more than memory. In Janmohamed’s poems, history is etched into the body and into the land. Through imagery such as this, she connects body and self to land, which opens the collection up into the later section “Re-turn,” where she writes “I am the path.”

A sense of grief is another prominent theme in the collection, as Jamohamed writes “an unbroken lineage of ache” (32) in the poem “Like this.” She turns back to ancestry for answers, writing: “How do I walk into the sun / of who I’ve become / without searching the shadows / of who I was” (32). Over and over again, there is no way to move forward without looking to the past. The past Janmohamed writes of is one that extends beyond the individual self. Each poem echoes with the accompaniment of many voices. The poem “Khizr” is dedicated to Elder O’Puck, as Janmohamed writes in the acknowledgement. In this poem, the narrator asks “where have you been all this time” and receives the response, “when did I leave?” (46). The poem “I Am My Own Beloved” echoes Sufi language for the figure of the Beloved. She writes: “The skill of your memory is sand the wind has already blown, beloved. / how many lifetimes will it take to remember? this body is a loan, beloved” (43). Not only does the self become akin to the earth, but it also aligns with the divine. In a context where the narrator is grappling with physical distance and national boundaries, borders dissolve along the path of the poems. Alongside the motif of the path, the doorway and mirror imagery feature prominently throughout the collection. “Mirror Gate” is a ghazal that depicts both of these through fantastical language: “A clearing in this old growth forest reveals the mirror gate. / Shimmering in and out of this world, there is no clearer gate. // If you walk a thousand steps in the opposite direction, you’ll / discover many ways to enter. But why forsake the nearer gate?” (16). But in this poem’s last couplet, instead of ending the poem with “nearer gate” as the poem’s radif indicates, Janmohamed writes “your heart the dearer gate.” In this collection, boundaries are constantly removed, revealing connections to both the self and the spirit. Reminders on the Path is a collection that comes in waves of tenderness and loss. The path is never easy to walk on, but in the embrace of ancestral guidance, it becomes possible to walk. Against a backdrop of national boundaries and displacement, Janmohamed writes of a unity between the self, the earth, and the divine. Manahil Bandukwala is a writer & visual artist. She is currently Coordinating Editor for Arc Poetry Magazine, & Digital Content Editor for Canthius. She is a member of Ottawa-based writing collective VII. Her collaborative chapbook with Conyer Clayton, Sprawl | the time it took us to forget (Collusion, 2020), was shortlisted for the bpNichol Award. Her debut collection, MO |