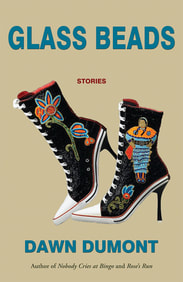

Dawn Dumont's Glass BeadsReviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

When Dawn Dumont was growing up on the Okanese Reserve, she imagined herself as Anne of Green Gables and, like Anne, renamed landmarks on reservation land. Anne reimagined an ordinary roadway as ‘The Avenue’ and Dawn renamed the garbage pit ‘The Mountain of Lost Dreams.’

Her girlhood Anne-phase allowed Dumont to view ordinary things in a different light, but it was tiring being someone else. Now an adult, she writes fiction which allows her and her readers to inhabit other perspectives. Writing can be tiring too, and Dumont acknowledges the “unfair pressure” on Indigenous artists whose existence is an act of resistance to begin with: she views her art as a way to “transform injustice into something larger than [her]self.’ This Nehewin (Cree) and Métis writer populates her fiction with a variety of characters from the Okanese Reserve, which appears in all three of her books: Nobody Cries at Bingo (2011), Rose’s Run (2014) and Glass Beads (2017). As a stand-up comic, she has a lot of experience writing short pieces; Rose’s Run is a novel, but the other books are linked stories. Survival stories. Set against a backdrop of cultural genocide. These are stories about ordinary Indigenous people living the legacy of the Sixties Scoop, Canada’s residential school system and other colonial systems designed with extermination in mind. The shared setting and the expansive cast suggest that perhaps these are stories told about a community rather than individuals, but every character matters: each part is essential for the whole to thrive. Dumont’s linked stories perfectly reflect a holistic worldview: interdependent narratives creating and sustaining a broader literary landscape. In Nobody Cries at Bingo, the main character is Dawn Dumont; she remains at the heart of the book throughout but time passes between the events chronicled in each story. In Rose’s Run, Rose’s work at the community centre offers readers a glimpse of many minor characters in the community who ultimately unite to combat an overarching threat. In Glass Beads, the focus shifts between four characters and unfolds across two decades, and here the spaces between stories are sometimes as important as the action in the stories. This pattern of connect-disconnect-reconnect, within and across Dumont’s books, is appropriate as Indigenous communities continue to heal a plethora of fractures in the wake of colonization. Whether they are dealing with individuals, families or communities, these stories are preoccupied with endurance and survival. Glass Beads opens with eight-year-old Julie fleeing the other children in her foster home on the reserve. She is impressed by Nellie’s matching red coat, hat and mittens when she meets her outdoors. Julie is inspired to introduce herself as ‘Angel’ and fantasizes about playing checkers and Nintendo as she follows Nellie into the kind of house where little girls wear clothes that match. The next story shifts to Nellie, who sits in a hallway outside a bar, on break from university in Saskatoon. The bus has dropped her off and she is waiting for family to fetch her, when Julie and another friend arrive at the bar. The girls haven’t hung around since elementary school, but spontaneously have drinks together. This is how it happens, how the connections loosen and loop around from another direction. The relationship between Julie and Nellie is at the core of Glass Beads, but their relationships with two young men are key too: Everett is also from the Okanese and Taz is from a northern reserve where his father is a prominent politician. There are alliances (and dalliances) between the four of them, but also tensions. And not only conflict, but pain. Even in quiet moments, the handles of plastic grocery bags are digging into a character’s fingers. And then, there’s addiction. Suicide. Abuse. And women and girls are particularly vulnerable. Julie tells Everett her mother’s story in such vague terms that readers quickly recognize how commonplace this kind of violence has become: “She went with this guy and he said she tried to rip him off and he beat her up. Then he dumped her in the woods.” In succinct summaries and in the gaps between stories, significant events unfold off-stage. In one memorable instance, a character’s black-out becomes a black-out for readers too, when the story told from his perspective stops unexpectedly. Understanding remains fragmented, incomplete. The refracted and reflected details are combined, and the slightly altered and damaged relationships on the other side of that binge offer some clues. This is one binge among many, however. Most occur out of sight and are arguably just as dramatic when they are not remarked on, when they unfold in the background, without commentary or a detailed description of their fallout. When readers are forced to consider what isn’t represented in a story, they are encouraged to place all that much more value on the aspects of the characters’ experiences that are represented. Yet, the unseen has substance too; it weights the characters, and, at times, its amorphous shape can become a burden. This is how history can load the present, how the legacy of the past can bear down on events in the present day. With Glass Beads, readers must assemble some of these characters’ history. This reflects an underlying narrative which also exists for many Indigenous youth who have this kind of assembly work to do when family members are unable to describe the trauma experienced as a result of the Canadian government’s genocidal practices and policies. For instance, some Indigenous survivors of Canada’s Indian Residential School (IRS) program spoke openly about their historical experiences for the first time in recent statements to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the summary is available online); such shared truths filled in the blanks for many younger family members who had inherited a permutation of older generations’ pain. The spaces within and between stories take different forms. Taz walks for a mile before he realizes that he forgot to share a central piece of news with Everett; readers wonder what was circling around Taz’s mind throughout that mile, what was bigger than that important detail that he forgot to relay. Nellie ignites a car’s ignition as Everett opens the passenger door to interrupt her departure, and readers must imagine what was said, because the next story abruptly moves into Taz’s perspective. Readers long to eavesdrop on an unheard conversation between Nellie and Julie, after one of them announces that they need to leave for the hospital and the other says “not -- yet”. Words in the Nehewin language are not relegated to italics (which represent characters’ thoughts) but are incorporated seamlessly into the narrative. Even off the reserve, a smattering of Native language connects these characters to their heritage. And their figurative speech reflects their upbringing: Nellie’s mouth is “as dry as month old baked bannock,” her heart gets snapped “like a hollow piece of firewood,” and a reference to the Zapatistas sparks a memory of seeing women and men stand together against Canadian soldiers at Oka. Off the reservation, Nellie is distinct, different. White people ask not-so-subtle questions designed to suss out her ethnicity (like “What’s your family’s background?”) because she “wasn’t dark enough to fit their idea of what a Native was but her skin had enough colour that they knew she didn’t belong to them”. But Nellie’s experiences beyond the reserve also become a barrier when she returns home: “Nellie stopped talking like she’d been unplugged. She should know better than to talk long about stuff like picking her classes.” Working with young missionaries in Mexico, she might be judged for not looking Native “enough,” and back on the reserve, she also might be judged for not being Native “enough.” Nellie inhabits an in-between space in the apartment she shares with Julie and in her experiences with other young Indigenous people living in Saskatoon. These characters experience challenges in unique ways, but the challenges themselves are experienced universally. Poverty, for instance: “And when you do well, you can’t have poor friends. Not because you don’t want to but because they don’t call you up anymore.” And racism, which impacts all of them, even the few Indigenous characters who profit from colonial systems. When Taz speaks dismissively about his work for the government, for instance, Julie questions his commitment to his co-workers: “They don’t give a shit. As long as I show up for meetings with a brown face. And that I got. In spades.” Taz appears to be thriving in the confines of this system, but he, too, is merely surviving. His addiction is an ineffective coping mechanism and his rage affects everyone around him. The humour in these stories, however, is vitally important. Much of it revolves around identity and relationships. There are no extended comic scenes, but there are pointed observations: “Julie wore a pair of sneakers, jeans and a KISS T-shirt. Nellie wanted to change – her clothes, her hair, her genetic destiny.” Nellie’s self-deprecating wit is also evident in the characters in Dumont’s other books, in Dawn (in Nobody Cries at Bingo) and in Rose (in Rose’s Run). Dawn had “a healthy appetite for a ten-year-old girl, healthy even for a thirty-year-old construction worker,” and Rose “was pretty sure that other than in her closet, the only other place you could still find acid-washed jeans was in a few eastern European countries.” These young women are drawing and re-drawing boundaries in their relationships. Nellie, like Dawn and Rose, has an idea of what she wants, but reality disappoints her and she wonders how much she must adjust her expectations. She tries, for instance, “not to read too many serial killer books because after a while she started seeing everyone as a possible murderer – like her roommate, for instance, who was secretive and manipulative,” although she was “also a real slob and serial killers tended to be anal and neat [and] … would probably make decent roommates.” “If you can laugh then you can survive until the solution arrives,” Dumont explains. So when it comes to the intergenerational effects of residential school, racist education policy, poverty, colonialism and discrimination, laughter is an essential tool in the work of survival. Dumont grew up reading Bible stories in doctors’ waiting rooms and W.P. Kinsella stories (on the advice of a librarian who wanted to connect young Dumont with some Indigenous characters in the absence of Indigenous writers in the library’s collection). Later, she discovered the work of writers like Richard van Camp and Thomas King. She knows the power of humour: in storytelling, in living. She also knows what it’s like to be on one side of a pane of glass, whether looking in or looking out or looking back. Because whether it’s a window or a mirror, glass adjusts our perspective. Glass transmits, reflects and refracts: it alters the world on either side. And one glass bead after the next makes a beautiful object, but the sequence can also disorient the admirer. Glass Beads is a pattern of stories, a kaleidoscopic reading experience, each facet bending the reader’s view of the world between its pages. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - including the Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg and the Wendat - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|