Interview with Arleen Paré

Interview conducted by Kevin Heslop

|

|

So, to begin, when I’m thinking about your work, particularly First and Last—but also some of your recent collections, The Lake of Two Mountains and The Girls with Stone Faces—I’m thinking about dualities, and I’m wondering whether this is a place to begin.

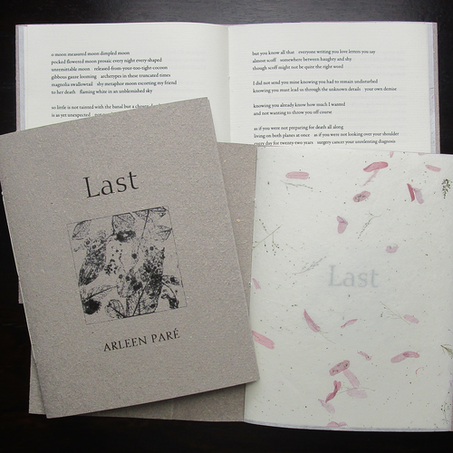

We have, this year, First, a full-length collection published by Brick Books and edited by Sue Chenette, and we have Last, a hand-sewn chapbook published by Baseline Press and edited by Annick MacAskill. And within First and Last, a contained diad, or call and echo, or opus and coda, the explicit dualities are several: we have life and death; we have childhood and maturation; we have Arleen Paré and Pat Hurdle; we have science and myth; we have the past and the present, the enemy and the friend. “All things come to an end. / No, they go on forever.” reads Ruth Stone’s epigraph to Last’s final section. And I often feel as if one could read The Lake and The Girls and these two new works as extended love letters full of music and longing and tenderness and curiosity. And I wonder whether you might free associate a little about the other, or the twin, or the relational energy or diad around which we construct our identities—and which feel, to me, to be thematically at the core of these books that you’ve written over the past decade or so. Um. Wow. That’s a great question. You could just leave it that way, Kevin—just the whole question is so beautiful that maybe I don’t need to say anything. *laughs* But no, I will reply, because a couple of things that you said prompted me. First, I don’t think I write anything without being in love with it. Mm. So that’s the way I start: I fall in love with what I’m paying attention to. So, for instance, The Girls with Stone Faces. When I first saw them at the National Art Gallery in Ottawa, I immediately fell in love with them, which was huge. I knew I had to write about them. Other things come to play, but that initial smittenness is the key. Mm. Those three books that you mention are love letters, because that is at the heart of almost everything I write; I don’t think I could write without it. And I call it love, but I feel energized when that happens—there’s an energy around whatever I’m focussed on, and suddenly I want only to pay attention to that. Right. The Girls was one example, and then Pat Hurdle, whom I had loved as a childhood friend, came back into my life, so that was delightfully easy to pay attention to. Then when she died—of course I wasn’t in love with her dying—I really wanted to write a memorial for her. Also, because—OK, I’m really free associating now—when she decided she wanted to die—she had this serious progressive motor-neuron condition, so severe that she couldn’t do things for herself at all—she couldn’t feed herself easily; she had to use a spoon and be very careful—and she was a fiercely independent woman, which was one of the things I loved about her; she was so much herself and enjoyed life as an independent person. When all her functions were so reduced, she was devastated. She had also been fighting cancer for 22 years. Mm. She was smart and independent and used the medical system when she needed to, but researched everything they told her to do. She was involved in her own health decisions. That’s the background; I wanted to honour that. As well, this was the first time I’d known anyone using MAiD, Medical-Assistance in Dying. It seemed like a huge paradigm shift. Mm. In terms of birth, we have been able to use cesarian section for decades. Now we can use MAiD. Suicide has always been available, of course, but it has its own taint. This seems like a huge change in the way my life would play out and the lives of many of the people I know would be playing out. And yet, I don’t even know how I feel about medically-assisted dying; I’m of two minds: I grew up Catholic, so I have a little anxiety about that—not for any real reasons but just because that’s the way my psyche was influenced—and I also have a Buddhist practice and they’re not that supportive about choosing to die either—doing anything, practically. *laughs* Yeah, actions are foolish, aren’t they. Well maybe they are. In any case, I have a small hesitation around it. Although when I saw Pat die—and I did see her die; this was the amazing thing; she was sitting there smiling at us—and she was smiling; she was so happy to get out of this veil—and I understand that; I’m not entirely in love with life all the time: it poses so many difficulties—and I don’t mean just when you fall down and hurt yourself; sometimes just getting up in the morning is a trick. Right. She was happy to leave and she was smiling and she had her two older adult sons sitting on each side—hard for them--and she had a group of friends—this was during CoViD—gathered on the balcony outside her bedroom facing a set of French doors. She could look out; we could look in. And then I saw her receive the injections and then she died, and it was stunning. You know, death is a mystery, and although I was right there, it was like watching TV. Right. It was very weird, and very powerful, intensely emotional to witness. And this was my first. You know, when radio first happened—when people listened to the first radio program—they might think Wow. This changes everything. And I do believe MAiD changes everything. It was such a big deal; I wanted to write Last for Pat. I couldn’t say everything in First. Right. So, back to the dualism: I don’t really subscribe much to dualism, but I should say the word twins--I love twins. I am wild for twins; I wish I had been a twin. That companionship forever just is such comfort for me. I do believe twins have it easier than the rest of us: they always have their person. Right. And mostly, I imagine, someone to agree with you all of the time. (Does this expose me as a narcissist?) I love that two people look perfectly alike. I’m mesmerized by that idea. I mean, there’s something supernatural or paranormal in the word "twin" in English. I’m not sure if the same aura of mystery hangs about it in other languages, but— How do you mean that—about the word “twin”? That we get some idea of the extra-normal, or—? Yeah, I think of it as a kind of rarity that has the sort of shimmer of something otherworldly about it. It is so rare: I don’t know very many, or maybe any, identical twins and it’s identical twins that I’m crazy for. I love the idea. You know, at the beginning of First, I wrote a poem about a twin dying in utero. I think this happens not infrequently, that there are two embryos and one of them dies before birth. People ask me if I think that was true for me, because I have such an interest in twins, but I don’t think so. I think it’s the companionship that I love. As well I love repetition, patterning, that kind of thing. Maybe that’s another of my attractions to twinship. It’s sort of everywhere in the work, especially in Last: I’m thinking of the refrain “What other side?” which you use as a sort of musical device. Do you mind if I ask you to free associate on the idea of refrain as musical device and what you feel before the refrain needs to recur in a poem? Does it feel like a handhold or a stabilizing or structural mechanism—or is there something related to prayer, perhaps, or to your religious upbringing? That may be true, having a religious upbringing and then falling away from it. I would not return to Catholicism. Not that I’m not fond of parts of Catholicism; I haven’t turned on it the way some do—but the ideas seem facile. Pat would say, leading up to her death: I’ll see you on the other side. And I would think— *sychronously* What other side? What other side? But at the same time, it’s a small comfort that many of us use, a pretense, you know? But the refrain is me questioning her: What are you talking about, Pat? That’s me kind of getting mad at her in a way—What other side? What? Mhmm. You’re leaving me. Of course, I understand how you must, but you’re leaving me on this side; wherever you’re going, I have no idea about that. Right.

But then she says, I’m going to be turning into a butterfly. You could do worse than a butterfly. Yes, you could: you could become a cockroach, for instance. *laughs* Although maybe from a cockroach’s point of view it’s not so bad, really. I mean, the world is full of food, I suppose, from a cockroach’s perspective. Full of food. And anyway, I think that refrain is me asking the question, What other side? But it’s also questioning why she’s doing what she’s doing: there are two parts: she needs to get out of this predicament and there’s no other way; and there’s me wanting her to stick around—and even as I’m saying this, I’m practically crying. I really did want her to stick around. Pat, in so many ways—because I think of friendships, and because of moving from Vancouver to Victoria—I left friends behind in Vancouver, not that I can’t see them, but—the whole idea of friendship is a conundrum. I love having people in the world. This seems like the appropriate moment—and I’d be remiss not—to ask about the Fiction Bitches and the Webbles. Yes. I wonder if you’d say a word about those two groups of your people in the world. The first group is called the Webbles. We named ourselves at my insistence. I had to have a name for the group; I know it’s silly. We thought of Webbles after Phyllis Webb. Mm. The names include the notion rebels, although none of us really are. We’ve been meeting for eighteen years; I really enjoy being with them, I admire their poetry, it’s important for me to see them. We spend half of the group saying hello and catching up and then each of us presents a poem or two for feedback. I think it’s useful to get this kind of immediate feedback—it’s how readers read poetry books: cold. There’s no scathing criticism. The feedback and suggestions are useful for shaping our poetry. It’s a companion group as well as a poetry group. With the Fiction Bitches, I haven’t been a member as long, but some of the Bitches are good friends as well. Both groups are really important. So, I imagine you in a writing workshop that you’ve been part of for a number of years and then things like the Governor General’s Award happen and these extraordinary collections happen and I wonder if that changes your comportment in the group, whether you’d intentionally do this or that to recreate and affirm the sense of familiarity and closeness and mutual interest. Did you find yourself interacting differently at any point as a result of the success as a writer that you’ve had in the context of getting together with friends, not all of whom may have achieved the kind of esteem or acclaim that you’ve received for your work? Well, they do make me wear a crown for the whole of the meeting. That’ll do it. So that establishes that. *laughs* It’s such an interesting question. I float around this all the time. I worked as a social worker for years and years; and the thing about being in a job that’s not in the art world is that there’s a job description; there are annual evaluations; you have a client base, or you have some tasks you’re supposed to attend to. Nobody says you’re a better social worker than your colleague Jane over here? Nobody’s comparing. Nobody’s comparing. Right. Sometimes a social worker will stand out, but apart from that, no. The comparison level is neutralized, it’s non-existent. When I became a poet, I thought, good god, there’s no job description; there’s no annual evaluation; I don’t get paid. Mhmm-hm. And there’s this hideous environment—I don’t know; maybe it’s just me—of comparison. It drives me nuts. I suppose I could stop it, but I don’t know how. I feel like we all just walk around with this horrible judgement and comparison and competitiveness—and I have to recognize it, of course. So—this is immodest of me but I feel like I’m a modest person—I just try to back off is what I do; and I try to do everything I can to mitigate the comparativeness. And yet at the same time—and maybe this is pathetic, but I want people to recognize the work. So, again there’s that duality: I want not to have to do anything, but I also want it to be known. So, yep. That’s my conundrum. Right. As if—I sometimes wish people would be familiar with a bit of what I do before I meet them or something—and I don’t need it to be talked about—but just for them to know who they’re speaking with; and I’d like to be able to reciprocate that. Exactly. Yes. Exactly. So, I’d like to ask you about the question of ego as it relates to writing, because this idea of competitiveness and of awards and the who-got-the-whatever-and-so-forth-this-year—it’s so antithetical to the experience of writing which, at its best, is really just about getting out of your own way. Yeah, yeah. And I wonder whether we could bring in what Buddhism has taught you about writing in the context of ego displacement or maneuvering around or circumambulating ego. So interesting. Well, I don’t call myself a Buddhist because there are some aspects I have some questions about, but I do have a meditation practice; I do go to Buddhist retreats; I read Buddhist material. So, yeah, that old ego thing. *chuckles softly* It’s very helpful to have this practice that slows me down, that tells me it doesn’t have to be all about me: it mitigates the competitiveness of the writing world which, as you say, is antithetical to what we’re trying to do. And it’s who gets awards, but it’s even who gets published. Mhmm. Mhmm. Like, there are people making decisions—judging—the whole way along. Right. It’s a weird mix. Just the fact that I got published at all was a miracle. And sometimes I fault the publishing world when it organizes things so mysteriously for writers. There are no policy manuals in publishing companies as far as I know. When I worked in social work, we had a policy that instructed workers to get back to people in 48 hours, no questions. And so I say to myself, Why can’t that happen in the publishing world? Right. But for so many writers, the suffering involved is beyond me. Sometimes I think I should just set up a publishing company and have my own policy manual, but I don’t. So, the meditation practice, Buddhism, helps to slow me down, to move me out of the primary picture. It helps my anxiety: so much of this is just anxiety. Anxiety based on whether we’re good enough. Mm. I don’t know. I don’t even know how to talk about it properly. But I do find meditation extremely useful. Sometimes if I’m meditating, I will have some lines of poetry or phrases popping around in my mind. I think, Oh no, please, just no. *chuckles softly* Do you have a Buddhist practice? I have been—yeah—meditating for about a year now. And it might sound pretentious or something, but I’m always just a little suspicious about nouns, in general— Yeah. Even “poet” I’m still a little uncomfortable with. Yeah. But I would prefer to say I have a practice. So I have been meditating; it’s been extremely helpful—absolutely essential, I think. So helpful. I know, I feel the same way. I don’t proselytize: people will find their own way to it if they need to. I think many people would benefit from it. Absolutely. Absolutely. So, I’m thinking about the twin-ness we were talking about earlier and, while Pat wasn’t a twin, she seems, at least when you met, to have been something of an equal. The lines “I eyed Pat and she eyed me back, unafraid. A good sign.” come up when you first meet. And a little later on, you say, “When Pat and I were on the phone sometimes we’d read each other magazine articles just to stay on the line lengthening the connection.” And I think about the importance of language in your friendship with Pat and that mutual desire for connection, and I wonder whether you’d say a few words about the development of that friendship, the sort of medial lacuna, that searching lacuna—where we have the appearance of Nancy Drew—and then its kismet refrain in 2011.

It was sort of like when I saw the exhibit of the Girls at the National Gallery; it was that kind of thing; I knew right away this kid was meant for me and I was meant for her. And I think we tacitly both agreed on that. The other thing: this was a street in the 1950s in the suburbs just outside Montréal, swarming with kids; and Pat and I were the oldest kids on the street—like five and six. The others were all swarming around our feet: babies and younger sisters and all girls, as it turned out; I think there were three boys, those poor guys. *chuckling* So, we were the oldest on the street which meant we were in charge—again, the hierarchies in our lives—so we knew immediately that we were going to be friends, and the way that I go into the fact that she had blonde hair and blue eyes and the fact that I had brown hair and brown eyes meant that that was a difference that I had to overcome. But then I did, of course, because I just wanted to be with Pat. And then I think she felt the same about me, not that we ever admitted anything like that. You know, it was the ‘50s and nobody said anything like that—least of all kids; we wouldn’t have known how to say that. Right. When I had to go to a different school and then move away from the neighbourhood, we grew apart and we both made different friends; but that early start set the tone for me for friendships. It was a very close and steady friendship. I was very comfortable. I don’t think we ever fought, Kevin. That doesn’t happen so often in one’s life. It doesn’t, no. We were, at that time, very agreeable. I think about, in 2011, when you re-connect after this period of apart-ness in your lives, how you approach, as a storyteller, catching each other up: you’ve said that it took you both a couple years to catch each other up on what had happened in the interceding period. Yes. And I think about memory and I think about your approaching that as a storyteller and that two-year-long process of catching her up. You’ve got this rapt audience member, or rapt reader, say; and I wonder what that experience taught you as a storyteller, and maybe as a poet, and what it taught you specifically about memory and how memory functions as you were recalling your life. Pat initiated it: she had photo-albums, things that people don’t have any more. And we would go to each other’s homes and pour over each photo-album—decades of photos from early adulthood, our children, our husbands. We used these as a prompts for our stories, our memories. She herself had a spiritual practice, Yasodhara, a yogic, ashram-based practice. She invited me to a weekly meeting of her group, her sangha, to do some yogic practices. I used to call it yoga non yoga because there was little yoga, as I understood it, involved. *chuckles softly* And there would be discussion perhaps light, for instance. Someone would lead it, and after the discussion we would be encouraged to draw something that reminded us of the discussion we had just had or something that related to light in our lives. Pat asked if I wanted to go and yes I did because I wanted to know everything about her—not because I wanted to join her ashram, but because I wanted to be with her doing what she did. I joined her for a semester. Later I met her two sons and she met mine when they came over from Vancouver. And my son Jessie, who’s now 51—he would have been in his 40s then—said, Oh this is the Pat Hurdle we’ve heard about. We were beginning to think you weren’t a real person; we thought you were a unicorn or something. *laughs* So, obviously I had been talking about her a lot. I have a pretty steady memory, and I think Pat did too, which was a benefit, selective, of course, but vivid. Speaking of selectivity, over these past few months you’ve been giving readings from these two works and I wonder what you’ve discovered about these poems, about Pat, about yourself, that you were unaware of in the writing, if anything. Well, you know it’s so interesting when you have to give a reading and then select fifteen or twenty minutes-worth of the book to present—and of course you try to present something that’s representative, but is also the best work. It was interesting to go through and decide which, for me, were most representative, but also the fairest in the land, those that sounded best in a reading. When I’m writing, I’m adding poems and arranging them and I don’t know yet, of course, which poems will make it into a reading. But the ones that make it to the reading are the ones that have the most rhythm and that provide a sense of what the book is about. I don’t know that I really learned all that much. I learned that I am allergic to Zoom. And every book is like that: I find my best poems and I rarely deviate from that first or second selection, partly because it’s easier, but partly because I think those really are the best. What would I read otherwise? Right. I did a reading—this was interesting—with a local book club for Earle Street, which was the book just before First, about the street where I live. It was a neighbourhood book club on Zoom and the person organizing it was very organized and she asked me to read certain poems that she had selected, maybe eight poems that I had never read before. And I thought, Wow, that’s curious, someone else has an idea about which are the strongest poems to read; and so I did read those poems, and it was delightful. It made me think my own poem-selection may not be perfect, but. Right. So, speaking of rhythm and performativity, I think Gertrude Stein’s influence is unavoidable in the context of conversation about your work—especially palpable in The Girls with Stone Faces, if only because Frances and Florence, lovers and near-contemporaries of Stein, were making the salon-like atmosphere in Toronto that Stein was making in Paris at that time; and her rhythms are everywhere in that book—but also in First: I’m thinking, for instance, of the unpunctuated sentence “This new girl had blue very blue eyes.” where the narrator catches the image and redoubles its intensity within the flight of the statement’s syntax and this has Stein’s and your agility and vigour and dispassionate attitude towards punctuation. Mhmm. Mhmm. And we have Fred Wah’s words on the back cover, “Arleen Paré’s First is an intriguing Gertrude Stein as Nancy Drew mystery.” *laughs* So, I wonder: what did the planet of Gertrude Stein bring to the galaxy of you, Arleen? Well, I think I have always been a bit of a dilettante regarding grammar. I use it sometimes; I don’t use it sometimes; sometimes I mash everything together; sometimes I use spacings instead; sometimes I use no grammar in lineated poetry, sometimes in prose poetry. From the start, which was in about 1995, I was allowed the freedom to choose for the poem’s sake. I do want the poem to make sense, so that the reader doesn’t have to suffer, but I felt that there were other ways that a reader could be guided, that a reader could take her breath. Mm. Stein is like that too––a maverick. I’ve only learned recently that that is considered unusual. You know Hoa Nguyen who teaches out of Toronto from time to time, the poet? Mhmm. I have taken a few of her courses and found them very productive, being deeply exposed to various poets. She taught a course on Gertrude Stein and Emily Dickinson together. Wow. Yeah, it was kind of wow. I read a lot of Gertrude Stein when I was taking that course and exposed myself to her work, to whatever experiment Gertrude Stein was doing— *chortling* I had never appreciated Gertrude Stein before; she always seemed too obscure. But I enjoyed her poetry when I started paying attention, when I started using her slings, so that I had to pay way more attention. And it seems on the face of it so simple, almost childlike, the way she operates on the page, but when I attempted to mimic her I found it was so much more complicated than I had ever anticipated. Right. And because I was writing First around the same time that I was studying Stein, I realized that her form could be useful for First. The repetition, because it seems, on the surface, a little childlike—and I was writing about childhood--so it just seemed ideal. Mm. So, on the topic of grammar and not feeling bound—as I don’t think any of us should feel bound—by syntax or punctuation, in some of the prose poems I notice that you use this technique that feels like you’re tracing the, like, inter-dendritic movement of one micro-volt of electricity as it moves through the associative tapestry of your mind and memory reminiscent of the state of trance one can induce if you slightly cross your eyes for long enough. *laughs* I’m thinking of the lines from “A woman gathers questions”:

And you get the sensation of early morning, of just having woken, the involuntary hyperconnective place just this side of dreaming; there’s something meditative about it; and so I wonder if you’d talk a little bit about the state of mind required for you to affect that style and that techinque, whether you can induce it at will, and how that neural transparency informs your thinking about what poetry can do and how memory works. It is very semi-conscious, also associative. I feel so fortunate when that happens. I think I could do it at will; I’m not opposed to doing it that way, but generally I’m more in a trance-like state—not exactly in a trance—I am just coming up with phrasings, words, as they line up in my brain. Mm. And, you know, as poets, I guess we could say, we love language, words; and then when they spring into other words and line up together—I love puns; that’s the other thing. I love humour. I think humour is one of the highest callings. I think, levity, we need it. Yeah. And so sometimes just the ironies of life line up for me, and sometimes words line up, and the rhythm and rhyming of words line up and I feel so blessed that I’m allowed to put them on the page that way. I get away with it; for me it feels more natural than anything else. On the topic of humour, I have sometimes felt that any statement uttered which doesn’t end with a punchline is a discourtesy. *laughs* Right. It’s almost an insult if you say something without a laugh at the end of it. Yeah, yeah. No, people just aren’t trying hard enough. So, I’ve got a couple more questions for you. The influence of science on your thinking: it’s everywhere in First, which is sort of woven with one’s origin myths and the origins of the universe and there’s astronomenclature and the language of cosmic origins everywhere in the book. We have the second section’s title “A Brief History of Childhood”, reminiscent of Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time; and one gets the sense that, beginning in your childhood, you’ve been enraptured with astronomy and the great grand scales that come with it. And I wonder if you’d say a few words about your cultivation of curiosity for the cosmos and how scientific thinking informs your work—and perhaps, too, whether that contributes to a sense of duality in the mind, of the scientific-brain and the poet-brain, or whether that duality, like so many, is a myth, that rather they inform and infuse one another. I do think that is a little bit of a myth, unfortunately, and that they do in fact infuse one another. And as people of the poem, I think we are not as familiar with science as behooves us. Mhmm. And also because, for me, for the longest time—and all the other questions are useful and fun and lead to cures for cancer, but—for me the big, big question is, how did this thing—we call it the cosmos, but it’s broader than that—come into being. Into being. Mhmm. People will say, Well, there was nothing and then there was something. And I think, What. Are. We. Talking about here? *laughs* What kind of an answer is that? It’s not an answer for me. I am so curious about that—almost to a point of vexation. My sister in Ottawa has the same irritation about it: Why can’t we know this? I have thought that the reason human beings are generally so anxious and irritable is because we don’t know this: we’re suspended in unknowing. And the unknowing about how a leaf works is one thing; but the unknowing—this significant unknowing—about where we came from— Mm. Mhm. Mm. You know, some people in the world perform long genealogies of—Like in the Bible, So-and-so begat so-and-so—you know, that kind of begattinghood— *laughs* Right. —That goes right back to the beginning. I think it’s in place of—We don’t know where we come from; how we come from; what—anything. We are beings infected with time. Fine. But why? I need a plain answer. Not a forty page equation because I don’t speak that language. Can somebody just tell me? I understand the desire to believe in origin myths, but that’s not satisfying: no, we can’t go there. I have been anxious about that for a long time. And when I started writing about Pat Hurdle, I thought, This is my opportunity to think about the big question, to pop it in there and explore it. So I read a whole bunch of information—Well, a few books, lay books. And I find them interesting. Astrophysics—not so much mathematics, but—there are scientists who write so that a lay person can understand it. I think I noticed Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Astrophysics for People in a Hurry in the Notes section. That’s one of the ones, yep. He writes very clearly, plainly. And then there are histories of science where you get to know who’s discovering what when. And a book about Schrödinger’s cat. Richard Feynman too. Right.

So that’s me just touching the surface. I don’t think I have the right kind of mind to delve more deeply. But I do think it’s been useful for me to have read the books. And in First, I wanted to write a poem in praise of all the curious scientists—Einstein, Planck—you know, all those who brought us to this place. I don’t know if I said this in the book but we now know—scientists now know—the origin of the cosmos is understood back to the first three minutes. Mm. Three minutes. Wow. That’s amazing to me. I never did write the praise poem and I’m sorry. I go to these Buddhist retreats; I say to the teacher in private one-to-one discussions that I want to know about origins—because there’s this whole idea of unconditioned origins in Buddhism—and I really want to know how we came to be. And the teacher almost invariably—not always—would say, That is one of the questions that the Buddha advises us not to persue. And I think, Oh. Come. On. *laughs* I may be misinterpreting, but that was the feeling I got when I was asking the questions. They didn’t ask, have you read deGrasse Tyson’s book? No. Don’t trouble yourself with that question. Not to speak ill of the wonderful teachers, but. Mm. It is a vexatious question, but I really am curious, I want to know. So I wanted to write a praise poem about these scientists who had enough sense of wonder and curiosity to just carry on in spite of impossibilities. I wonder whether there’s something about Buddhism that is not perfectly complementary with science in the sense that at the core of science is longing and the desire for more knowledge and Buddhism aligns more with the avoidance of needing to be anywhere other than just where you are. Yeah, I guess that’s a little bit true, but when I think about—I mean, the Buddha; what do I know about the Buddha? But anyway— *laughing* —The idea that he has said that you just need to study your own body, your own mind to have awareness. And there are/were giant libraries in Tibet, massive amounts of information, so it’s hard to say that they’re opposed to study. I don’t know what to say about that; that’s a whole study I’d like to make. That would take a lifetime. Well, if the Buddhists are right and you’re reincarnated again, then you’ll have another lifetime to study it. Oh, no, actually, Kevin I have requested no reincarnation, no return. This means you’re at your apotheosis? There is a little check box which you can check, and I have checked it; I don’t want to come back. And you can just check that box too. Make sure you check it if that’s what you prefer. To whom do you direct that letter, Arleen? Ah. Yes, well, I am counting on telepathy here. Ah. Exactly how and where to, I don’t know. |