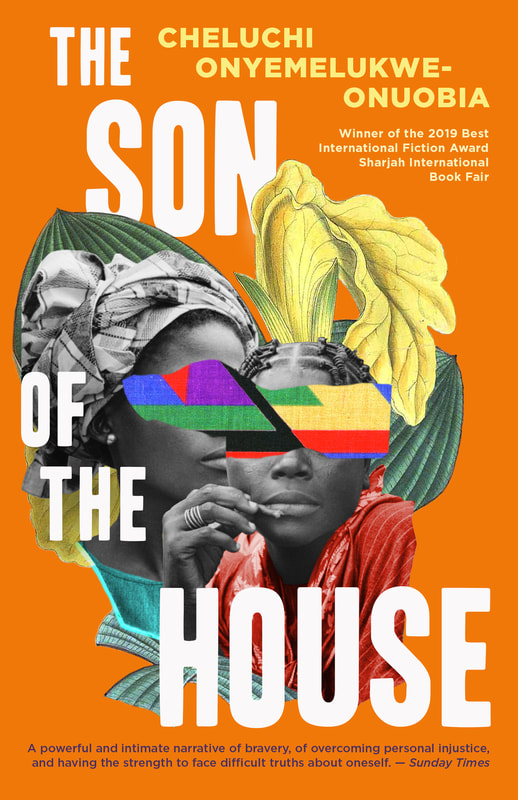

The Son of the House,

Reviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

When Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s debut novel opens with a kidnapping, readers are held captive from the start. Originally published by Penguin Random House South Africa in 2019, The Son of the House focuses on two women who await ransom payment in 2011 Nigeria; when they share their stories, they discover they are bound together beyond their restraints.

Nwabulu begins her story in 1972. After her mother dies during childbirth, her father’s remarriage is the first in a sequence of devastating events “that told me that love was not just food and shelter.” Her childhood comprises the bulk of her narrative, but she continues to face dramatic challenges as she approaches womanhood. Julie—a “brilliant girl,” the first from her village to attend university—begins her chronicle in 1973, but focuses more on complications that arise for her as a young woman. Her brother’s experiences in the army in 1968, from the age of 24, cast a particularly long shadow across her life: “He was not the only one who went to war. We all had scars from it.” Vulnerability unites them, as literal and figurative losses unfurl. Nwabulu, as a young girl, and Julie, as a young woman, travel paths with increasingly narrowed choices. Other people’s needs take precedence over theirs, and child-bearing is intended to comprise the core of their existence. Even Nwabulu, for whom child-bearing is twinned with death in her personal experience, accepts this:

Expectations of Julie are similarly clear: “My mother had…never really said anything beyond the fact that a woman must have children to be called a woman.”

Nwabulu and Julie both embody the concept that womanhood is synonymous with motherhood but their divergent individual life experiences afford readers the opportunity to compare and contrast the development of girls and women. “You are somebody’s child until you become somebody’s wife.” Julie’s mother says. For about half the narrative, readers observe a child and, for the other half, a wife. Both situations contain disappointments and sorrows. In one: “I dared tell no one that the night had become my enemy, just as it used to be a friend longed for amid the day’s endless chores.” And, in the other: “Helpless against his drinking, his determination to self-destruct.” Perhaps because these characters struggle, there is a weight to the prose; attention-to-detail and observations of daily life build credibility but demand patience. Each narrative, however, also features a dependable, committed female friendship. Plot and story reign, but their success reside in characterization, and these friendships significantly impact readers’ investment. These fragile but enduring support systems benefit both characters and readers; even readers who grow impatient with specificity and quotidian detail will be buoyed by these secondary characters, every bit as credible as the protagonists. When Nwabulu works as a housegirl for the Obidiegwu family in Enugu, she meets Chidinma, who is working for the Aniagolu family. They share jokes and confidences and, ultimately, their acquaintance affords Nwabulu options that she wouldn’t have had otherwise. Julie met her friend Obiageli when they were at Girls’ High School Aba and she, too, creates opportunities for Julie and encourages her to take risks that alter her future. The class differences introduced via these characters are fascinating, as is the contrast between rural and urban life, which becomes even more pronounced as the girls’ experiences of the world broaden. Older women in the narrative offer glimpses of how circumstances alter cases. For instance, Mama Nathan’s remark to Mama Nkemdilim: “When my husband lived, he beat me until my people threatened to beat him up. Yet, when he died, I knew that life was more difficult for a widow than a woman, even a woman who had married a man who beat her.” The persistent fractures in Nwabulu and Julie’s lives are similar. This observation belongs to one narrative, but underscores a reality that affects both women fundamentally and lastingly: “There was an unfamiliar dishonesty in him. I think it was this, more than anything, that I disliked—this obstinate refusal to acknowledge that something was wrong, this determination to speak less than truth.” After each woman shares a substantial part of her life story, Nwabulu and Julie recognize reverberations, and the novel’s final chapters alternate as they relay their present-day—2011—realities. The kidnapping itself does not occupy the heart of the story. Unlike Roxane Gay’s An Untamed State, which considers the experience and after-effects of trauma in a Haitian kidnapping, and Edna O’Brien’s Girl, which fictionalizes the experience of a girl who escaped from Boko Haram kidnappers in Nigeria, the focus is backstory. Concentrating on Nwabulu’s and Julie’s lives in The Son of the House, readers witness the interplay between tradition and colonialism, recognizable to readers of Nigerian classic fiction like Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood, Chinua Achebe’s African Trilogy, or Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters. Nwabulu observes, for instance: “Everyone agreed that, as much as English law had come with the colonial masters, and Christianity had come with the missionaries, these institutions did not interfere with certain accepted and ancient traditions.” Some aspects of Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s story will resonate with readers of contemporary Nigerian stories too: Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀’s Stay With Me, Lole Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives, and Yejide Kilanko’s Daughters Who Walk This Path also consider violence and female vulnerability, motherhood and infertility, marriage and class. Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s The Son of the House is solidly engaging and was shortlisted for the 2021 Giller Prize and won the 2020/2021 Nigeria Prize for Literature. It’s a story about choices: “The choice was clear between bringing a child into the world with no name and bringing a child into the world with a father.” It’s a story about the absence of choices. It’s a story about the inherent contradictions and interconnections that proliferate in the lives of girls and women. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|