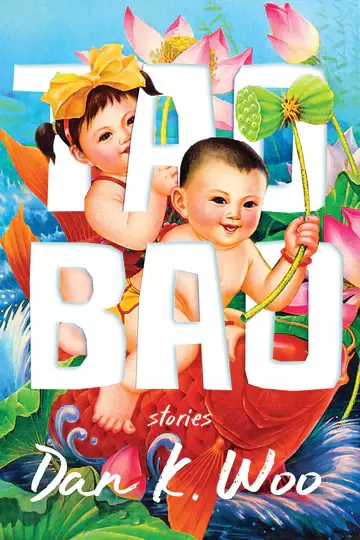

Taobao

|

|

Taobao, Dan K. Woo’s debut collection of stories, is by turns fanciful, tender, gritty, and discomforting. The stories are set in China, and feature a wide cast of characters, ranging from brides to students, a delivery man, an English teacher, and several iterations of the author himself. The settings are equally diverse, including large urban centers, smaller, sleepy cities which are remarkable only because of their marginalization in comparison to larger cities like Shanghai, and isolated villages. Regardless of the protagonist or the setting, the stories share a common affect: deflation, disappointment, at times ennui, at other times a painfully immediate sense of loss and failure. These are not stories that end well or easily. Even when characters get what they want, it doesn’t come with any satisfaction. It is as if the let down of an online purchase that turns out to be anything other what it appeared to be, that arrives as a shoddy facsimile of what you put in your shopping cart, that is a second-rate knockoff instead of the real thing, has been woven into the fabric of the characters’ lives, and, indeed, into the world of the book itself.

Regardless of the characters’ backgrounds, levels of education or worldliness (and these vary substantially), they are almost uniformly defined by a deep naivete: a female student thinks that she can seduce her much older English teacher into marriage; a teacher never expects his colleague to resent him for being promoted to principle. Time and again, characters appear clueless, unaware of the impacts of their actions, of the events that are unfolding around them, or of how those events will impacts them. This can be sinister. In “The Blonde Teacher,” an art student is completely unaware that his infatuation with a white English teacher is becoming dangerous and his behaviour is escalating to stalking. But, most of the time, the protagonists are hapless, as innocent as someone who believes in an online deal that’s’ too good to be true, and prey to the more savvy characters who surround them. Regardless of whether these innocents are sinister or well intentioned, their naivete always works to reveal a world that is both brutal and brutalizing. The student who schemes to seduce her English teacher into marriage succeeds in getting herself invited back to his apartment where it is quickly revealed that she is the gullible one: he charges her for a private lesson, and then convinces her to let him photograph her naked before having sex with her and sending her on her way. He posts the pictures online, she is expelled from the school, and he waves to her as she leaves the campus in defeat and humiliation, her life and her reputation ruined. The art student arranges a public proposal that involves his male friends surrounding the English teacher, trapping her in the middle of a mob and chanting at her to marry him. She recoils in fear and refuses, and he punches her in the face, beating her for rejecting him in the middle of the baying crowd. These stories play out in a world that is appropriately shabby, and rendered with an attention to the material details of decay that is one of the book’s strengths: everywhere characters turn, there is dirt and grime. The walls of a mud hut in which a prospective bride lives in a village are slowing flaking away, covering her face with mud as she sleeps. Metal is rusted. Restaurants are pungent with smoke from the diners’ cigarettes. And bathrooms smell pervasively of urine. The book itself smells a little at times, so powerfully does Woo evoke the sensory memories of filth. Escape is rare, and happiness is even rarer. When characters find it, it is fleeting, or, in its own way, perverse. A young woman in a village marries two brothers, tending their shared house and sleeping with them on alternate nights. Eventually, she has a threesome with them, and the story closes with her at breakfast, happily touching both brothers who seem unfazed by the night before, but will not meet each others eyes. At the end of another story, a character sticks his head through a hole in a brick wall to see a pastoral landscape that stands in stark contrast to the grime of the city in which he lives. He feels the wind on his face. But this is and can only be a momentary reprieve. It is barely real. It might be a dream, a vision, a sudden swerve into fantasy so emphatic is the story’s and the book’s portrait of a degraded and degrading world. The effect of the Taobao is striking. Woo’s stories make for difficult, often discomforting, but necessary reading. They linger, not always easily, but like the best writing should, long after the book is done. Aaron Schneider is a Founding Editor at The /tƐmz/ Review. His stories have appeared/are forthcoming in The Danforth Review, Filling Station, The Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Pro-Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, BULL, Long Con, The Malahat Review and The Windsor Review. His stories have been nominated for The Journey Prize and The Pushcart Prize. His novella, Grass-Fed, was published by Quattro Books in the fall of 2018. His collection of experimental short fiction, What We Think We Know (Gordon Hill Press) was published in the fall of 2021, and his novel, The Supply Chain (Crowsnest Books), is forthcoming.

|