Swing

|

|

Before she was able to wrap her mind around what she’d agreed to, Lillian had committed to attending a Wednesday night dance class with the new neighbour, Avery, who she immediately pegged as single; married women didn’t dance with strange men, and married men didn’t take their wives to a dance class.

They decided to carpool. Before the class, Avery came over and Lillian showed off her house. Her husband Kurt, thankfully, was out. “This is Baker,” she introduced Avery to her son. Their intrusion arrested him mid-slunk between the couch and the television. His reddened face made Lillian appraise Avery peripherally. She was good-looking. Younger than me, but not thinner, she thought gratefully. “Hi, Baker!” Avery said. “Hey,” he said. Lillian had thought having a child would be exciting, but the son was just a carbon copy of traits she’d grown sick of in herself and her husband, with an added learning disability. This year, they were trying homeschooling. She didn’t say any of this to Avery. Instead, she rolled her eyes and apologized. “Teenagers,” she said. She opened the other doors of the house so Avery could peek inside; Baker’s room, the bathroom, the linen closet, as if Avery might need to know where the blankets were, say, if Lillian were to die. “Oh, you have a dog?” Avery pointed to the large dog bed in the master bedroom. Lillian shook her head. “Not for a while.” “I’m sorry,” Avery said, and for a brief moment, reached out and took Lillian’s hand in her cold, smooth one. On the way to the church, Avery kept flicking down the passenger mirror of Lillian’s Subaru and grimacing at it, then flicking it back up again.

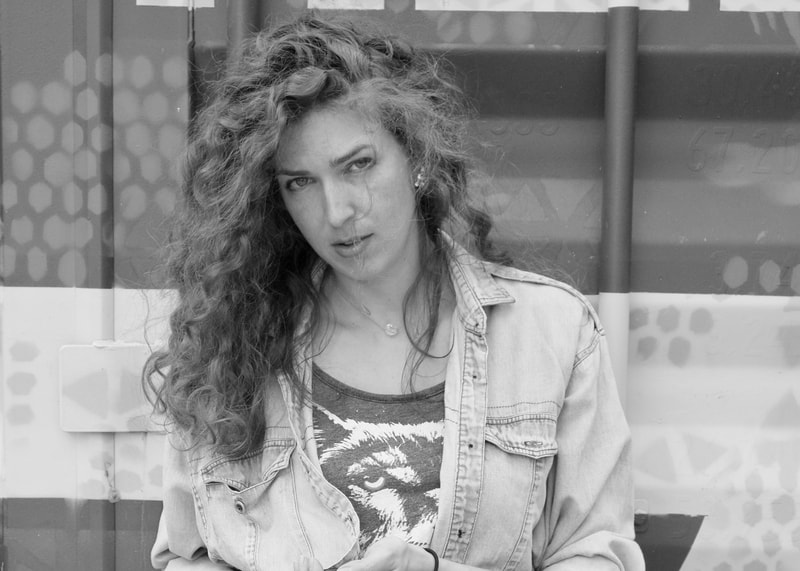

“I should have put some makeup on,” she said to Lillian. “I look disgusting.” Her husband rolled his eyes when he heard talk like this. “Females,” he would say. Lillian, too, said what she was supposed to. “No, you’re not,” she said. “Shut the fuck up, you’re so pretty. I wish I had your eyelashes.” Avery flicked the mirror down again, moaned. “I just lost track of time. I can’t believe everyone’s going to see me like this.” “Everyone” was two dozen people dotting the pale yellow basement of Emmanuel Presbyterian church like raisins in a loaf. Lillian had always thought that church basements were sad. All the glory happened upstairs. The basement was for things like AA meetings, support groups for the bereaved, bake sales where the crumbly cookies tasted like the plastic wrap they were smothered in. Low ceilings. Beginner’s Swing Class was well underway. There were more men than women, which she hadn’t expected. In rows, they practiced the basic step and were practicing it, heating up with physical activity, insecurity, a combination. Lillian could smell the places where their clothes touched their bodies. They were all trying not to watch their feet. The instructor, who had an arm span of such breadth that her every gesture blew eddies of stale wind over them all, kept up a ceaseless bawl of encouragement from the front of the room. Lillian was embarrassed being there, but every time Avery met her eye, she smiled open-mouthed as if she couldn’t believe how good a time she was having, down here in the mildewed basement of this church. Except for Lillian, all of the students knew each other. During the break, they hovered around the water cooler, which was mossed with condensation in response to the ambient temperature. They all glowed with exertion. One man pulled out a protein bar and chowed down, ravenous. Really? Lillian thought. “This is Stan,” Avery introduced them. “He’s a veteran.” Stan nodded. “This is my seventh cycle.” Lillian frowned. “You mean you just keep taking the beginner class? Over and over again?” “There’s only the beginner class,” he said, rolling the wrapper of his snack up like cigarette paper. She looked around at the others, sipping cones of icy water as if they were still thirsty, and felt sorry for them as a group, herself included. As she’d been stumbling over the basics, wondering at the sense and inherent vulnerability of learning something new at her age, she thought at least they might be a foundation on which to build. It seemed that wasn’t the case. They were doomed to be eternal greenhorns, never to matriculate. After the break, they did drills. Everyone moaned, and the instructor clapped her hands. “I know, I know, they’re hard. But remember, it’s great for weight loss!” While she tried to keep up, Lillian watched a woman two rows ahead of her working up a sweat. It amazed her, the lengths people would go to be socially acceptable. We do more to avoid pain than to achieve happiness. She’d read that somewhere, and that’s what she was thinking as she watched this woman sweat a ring around herself on the floor. Would she work that hard to have an orgasm? Lillian wondered. Probably not. But if it meant squeezing into a smaller size, for goddamn sure. Her husband was having an affair with a cashier at Foodland. Lillian knew her and knew about the affair, but let the fact that she knew remain secret from her husband. The care with which he tried to hide it from her told her that he still cared about their marriage.

But she knew. It was a small town, and she was reluctant to give up the ordered moments of human interaction she was allowed, one of which was making small talk with said cashier, whose name was Celine. Celine was as thin as the space formed between the teeth when saying her name. They already had a rapport; the only thing that changed was the topic of conversation while Celine ran her produce over the scanner. Lillian consulted her on Kurt’s moods, his misgivings. She found out that he complained about his lack of wealth and the shiftlessness of his son with both of them. She got Celine to tell her when they were having a date so she could schedule her nights accordingly and stock up on do-at-home face masks and flavoured vodka. She had tried them all. Cucumber was the best, in both. These nights usually ended with her trying to sense what her husband and Celine were up to. She knew him so well—better than anybody—that she thought if she kept her body perfectly still and her mind receptive, his actions and moods would be communicated to her over the distance. Sometimes it worked and she would look at him knowingly when he came home and for days after. That drove him absolutely batshit crazy. On the last Wednesday of every month, there was a social after class so that the students could practice what they’d learned by dancing with each other while the instructor played Motown and pointed out their progress. Some of the women got way into it and wore poodle skirts. Avery, Lillian noted with relief, was not one of them. Stan wore a suit that looked like it only came out of its dry cleaning bag for special occasions. Shiny and crisp, she could almost see the plastic still crackling around it.

“He’s been taking the classes for a year,” Avery fed her ear. “He flips houses,” she said, admiration blushing her cheeks like they were talking about someone who’d won a Nobel prize. She got tongue-tied when he asked her to dance. Lillian stayed rooted to the wall and watched them. Avery was light on her feet, the head of a rose being tumbled by a gust of wind. Stan led her, using advanced moves that Lillian hadn’t learned yet. Dancing, he gave off the impression of a very confident man, but when he came over to the table and spoke she could tell that he used to have a lisp and that it had been painstakingly curtailed. After he danced with Avery, it was unavoidably her turn. Stan bobbed back and forth in an effort to get her to try at least the basics. “You can do it,” he tried. “No I can’t,” Lillian insisted, standing stiff as a brick until he relented and they danced as haltingly as teenagers at prom. She could smell his breath and feel the sweat dampening his suit at the shoulder. He told her about renovating his kitchen, ruminating on the process like he had a quota to reach on the word “drywall” and he had to meet it by the end of the day. “And you do all that yourself?” she asked. “Yes,” he said. “That’s so impressive,” she said, losing her tongue in her teeth over the sibilance to see how he reacted. He didn’t. “You’re doing great, Lillian,” the instructor called to her, clapping her hands. Fuck you, Lillian thought. When she started home-schooling him, Lillian told her son that he would have to get a job. In her opinion, it was a better education than she would be giving him, and it would get him out of the house for about the same amount of hours that school had.

He got a job moving boxes around in the warehouse of a furniture store. “Put some muscle on ya,” her husband said when he heard. The boy shrugged, but Lillian liked this image of her son, brawny and tough, carrying a girl on each arm. Someday, not now. But soon. He always made a hasty getaway when Avery came over. He never used to do that with her other friends, or other acquaintances, she should say, that she brought over to the house. Avery dropped in once or twice without calling first and then she did it all the time. She brought over the ingredients for sugar cookies and they baked together in Lillian’s unrenovated kitchen. At the end of the day, Avery divided up the cookies on two plates. “That’s ok. You take them all,” Lillian said. “You don’t want to keep some for your son?” “No.” The main topic of conversation was Stan. “He wants me to come over and practice.” Avery didn’t put air quotes around the word “practice,” but they were implied. “So? Go,” Lillian said. “I don’t want to go alone,” she hedged. “Why? What do you think will happen?” “Nothing. Stan’s a really nice guy,” Avery said. “I’d go if more people were going. Will you go?” Lillian shook her head. “I can’t,” and gestured around her, raking in the prior commitments of family, motherhood, homemaking. She’d had a best friend, once. Emily. In college. They ate cheesy popcorn together and licked the powder off of each other’s fingers. They walked around campus reciting poetry aloud. They bathed each other’s eyes in saline drops the morning after margarita night.

When Emily suggested they get matching tattoos, Lillian went, bared her ankle gamely, her hisses of pain and questions about why they were doing this muzzled by love. It was a square with a circle inside it. She still doesn’t know what it means. Then Emily got into a program that took her on exchange to Hong Kong. Lillian didn’t even know she’d applied; if she had, she would have applied with her. She sent an email, asking how it was going. Emily never wrote her back. Her life was an hourglass that all the sand had drained out of, except the two grains of her husband and her son. Now there were two new things, Avery and the dance class. She didn’t care about swing, but that wouldn’t stop her from using it to her advantage. She checked that Avery’s car was still in the driveway before she left. Stan’s house was in a part of town that she rarely bothered with, the more desirable part, close to the lake where the sand from the beach sifted itself into the lawns.

He looked surprised to see her, but he’d clearly been expecting somebody; the house was ablaze with light, there were drink selections and a bowl of chips set out on the coffee table. Amiably, he showed her around. He was wearing a suit again. The fabric was slippery; whenever he raised an arm to highlight a feature of the house, his shirt came untucked. She didn’t avert her eyes when he tucked it back in. When there was no more house left to see, they practiced. Stan streamed videos onto his television showing new moves Lillian tried to imitate. He was relentlessly patient with her. As she suspected, dancing meant more to him than just dancing. In the space between songs, he bent his head, almost as an afterthought, in order to kiss her. She pulled away, but not completely. “I don’t want to have an affair,” she told him. “I just want my husband to think I’m having an affair.” He thought about it. “I need a practice partner,” he said. “Fine.” She handed him a slip of paper with a number written on it. “Call the house once in a while. If he answers, hang up.” She stopped doing quizzes in magazines a long time ago, but sometimes in the checkout line at the grocery store while she was steeling herself to talk to Celine, she would glance at them. What is the most important quality in a lover? one of them asked. Is it a) the ability to listen, b) a willingness to experiment, or c) a rocking hot bod? None of these answers were satisfying to her.

On their first date, her husband took her to a very expensive restaurant. They were still in college. This was after she no longer had Emily. She dressed up, ordered the cheapest plates, sipped her wine demurely, and thought, overall, that she performed very well, but still got the sense that he was disappointed. Halfway through the meal, he started manhandling his utensils like a doctor about to do surgery on his worst enemy. He ate and smiled without showing his teeth. When they left the restaurant he hailed her a cab but didn’t get in it with her. She hung out the door, frustrated, and demanded to know what she had done wrong. His gaze was ice as he looked at her. “What kind of lady wipes her hand with her mouth, instead of using a napkin?” She was shocked speechless and let him close the cab door without another word, riding home in silence. She stared at the offending hand on which she must have wiped her mouth, but couldn’t even remember doing it. They still had dinner together, Lillian insisted on it. No eating transfixed in front to the television or scarfing meals over the stove or leaving plates covered in the fridge. The family unit needed a minimum of maintenance, in her mind, and family dinners were part of it. So they could catch up on each other’s lives.

“Maybe you could take me to the classes,” Baker said when she mentioned them. He probably didn’t mean it, was just sucking up, but still, Lillian froze. Her son messing with the cogs of her machinations, that was the last thing she needed. “You don’t want to do that,” her husband said. “That kind of dancing’s for sissies.” As he said it, he stared at her, chewing, oblivious to how he’d just saved her. My hero, she thought. The phone rang, and her husband rose to get it. He said hello, a few seconds passed, and then he hung up. Lillian didn’t ask who it was, which earned her a long glare across the table. Then he turned his attention to the boy. “Why don’t you eat?” he barked. Baker twitched but didn’t answer. He’d come home from a few shifts, now, with his pupils needled, skin sheened with sweat despite their underperforming furnace. Cocaine, Lillian figured. He probably didn’t think his boring old mom knew the signs. Thoughts of the men who worked in the warehouse, corrupting him, kept her up at night. What was the most important quality in a lover? She mused, fiddling with her corn and peas. Vulgarity, she decided. What was the most important quality in a husband? Forgiveness. It took her a while before she realized that she should go over to Avery’s house and be shown around. She went, and found out that Avery had a hobby. Basket weaving. The baskets, stacked in cylindrical piles all over the room, were church-basement sad, but Lillian, who empathized with the inexplicable necessity of trying on hobbies like patchwork quilting and needle felting, praised them through the roof.

“What do you do with all of them?” “Give them away,” Avery said, pulling a few out of a pile, her “favourites,” so Lillian could see them. Then: “He asked me to come over and practice again.” “Who?” “Stan.” Lillian sucked in her lips, lifted her eyebrows. “What? You don’t think I should go?” “You don’t want to seem too forward. This is a small town. People talk.” She picked up one of the baskets, tulip-shaped, the spokes of whatever natural material it was made from sticking out dangerously all over the top. “Who taught you how to do this?” she asked. “My ex,” Avery said. “He was from Peru. He had this long, silky black hair that he kept in a braid down his back.” “What happened with that?” “I didn’t want to get married, and he lost interest.” “You think he was just using you to get his green card?” “Why would you say that?” “They’re all using us for something.” She waited to see if Avery would agree with her. Probing for darkness. “I hope that’s not true,” Avery said. She pointed to the basket in Lillian’s hands. “You can have that one.” Lillian clutched it to her chest as if it was all she’d ever wanted. Despite herself, she became quite a good dancer, the practices with Stan paying off in un-looked-for dividends.

“You’re getting better,” he told her after one session. He kept a roll of paper towels on hand to wipe the sweat from his face, his neck, the back of his hands. He produced a lot of sweat. “See what I said about your centre of gravity? You want to raise it up, makes you lighter on your feet.” He made a motion like he was lifting breasts. To legitimize their arrangement, Lillian took all his advice and tried to be a good dance partner, but she didn’t think she had any control over her centre of gravity, nor could she feel this elusive anchor that resided within. She hoped he was right, nonetheless; that her weight was rising, would continue to rise until it went through the top of her head and staying on the earth was a matter of choice. It’s a small town, and people talk.

Avery found out, somehow, that Lillian had been seeing Stan. “Been seeing,” that was how she put it when she showed up angry on a wet, grey afternoon. If that’s what people were saying, then Lillian knew her plan had worked. Rumours were the only grist left in an old mill town where the mills were no longer running. The success of her plan didn’t surprise her, but Avery’s hurt feelings did. She was taken aback that Stan’s boring bathroom stories and sketchy hairline were capable of bewitching someone so; but then again, look what she had married. “You told me not to go,” Avery said. Instead of sounding like an accusation, it came out like an appeal, as if Lillian could undo what had been done. She found the application of that power to herself terrifying. “Why would you do something that someone you just met told you to do?” she asked Avery sternly from the safety of her house. Avery’s eyelashes, the eyelashes that Lillian had said she wanted, shone black with ugly tears. When she leaned in, they pierced the screen door like thorns, and her breath came in a hot cloud in Lillian’s face. “I want my fucking basket back.” She went to the next dance class, knowing Avery wouldn’t be there since her car hadn’t left the drive all day. Stan wasn’t there, either. The others avoided her, and the instructor didn’t tell her that she was doing great. She left with the satisfaction that probably, by now, the whole town was talking about it. She made one more stop, just to be sure.

At the Foodland, Celine gave her a dirty look and dropped her receipt on the muddy floor instead of handing it to her. Lillian smiled at her regardless. If Celine knew, then her husband knew, and it was only a matter of time. Dinner was dead quiet. Lillian caught her son staring out the darkened windows toward Avery’s house. He poked at his dinner. She hoped he would lose his virginity with someone like Avery. She was kind, expressive, and would forgive him all his faults.

Her husband ignored her so deliberately that she had to hide her amusement. He went straight to their bedroom after finishing his meal. Lillian lingered on the dishes, flicked through the stations on the radio until she found a song she could swing to, if she wanted. She didn’t. Her son, oblivious as always to the dynamics of the household, wished her goodnight, sweetly. She had a physical urge to tuck him in, but she resisted. He was too old. The bedroom was dark when she went in, and she undressed and got into bed, leaving plenty of space between herself and the stiff silence next to her. She watched her phone on the night table for a long time and considered picking it up, now or in the morning, and sending an apologetic missive to Avery. She would explain that she and Stan had only been practicing, that she’d been too self-conscious to have Avery there since Avery was so good at dancing. She could share details about Stan that Avery might appreciate, if she was still interested in pursuing him. She was sure they could work it out, but only if she made the next move. It was up to her, now, the future of this friendship. Whether it was their first fight, or their last. She was nearly asleep when he shoved her in the back, waking her and nearly pushing her to the floor. When she turned, his face wasn’t his. It hung stony over her, and prickles of sweat salted her flanks. “You sleep over there,” he said. He pointed to the dog bed. “Kurt, I’m tired,” she said, reaching for the cover to pull it back over her. He wrenched it away, exposing her nakedness to the dense air of the bedroom. He pointed again with a fist full of cotton. “That’s your bed.” She peeled herself off of the cold sheets and felt her way in the dark to the large padded bed on the floor, got to her knees, and tracked circles within it like he’d shown her during their courtship. She could feel his eyes on her back, his fist thumping the duvet as he jerked himself off. Lying down on the familiar bed, she curled into the fetal position, mouth open to accommodate quick breaths, cunt walls drawn up in anticipation. It might not happen tonight, but it would happen. What was the most important quality in a mother? She recited. Knowing when to leave well enough alone. What was the most important quality in a wife? Knowing when to take it lying down, and more importantly, when not to. Jen Batler is a writer and editor from rural Ontario. Her words have appeared in Puritan Magazine, The New Quarterly, and elsewhere. In 2019, she was selected to read as part of the Emerging Writers Reading Series in Toronto, and she was recently awarded a Canada Council of the Arts grant for her memoir-in-progress.

|