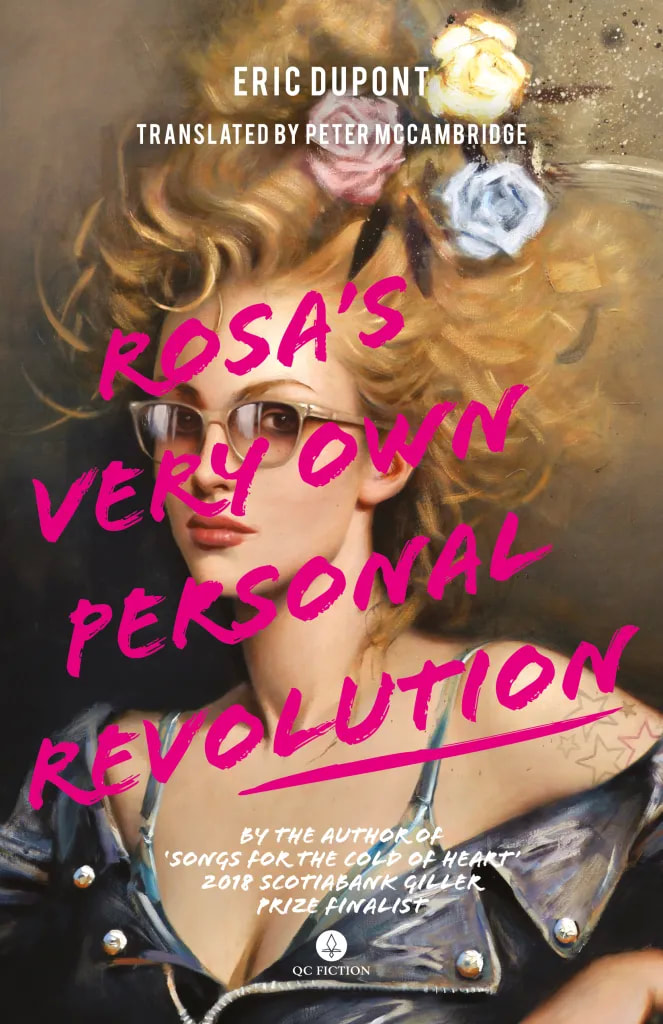

Rosa’s Very Own Personal Revolution

Reviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

“Twenty-six letters come up ridiculously short when you’re trying to bring across the full complexity of human relationships,” one character observes in Rosa’s Very Own Personal Revolution; Eric Dupont, however, drafts all twenty-six letters into service to create an unforgettable tall tale.

This is Dupont’s second novel, Peter McCambridge’s translation of 2006’s La logeuse—the book Dupont cites as his favourite. “I don’t think I’ve ever written as freely since,” he says of Rosa’s story, which won Radio-Canada’s “Combat des livres” in 2008. https://quebecreads.medium.com/interview-with-author-eric-dupont-e22ccd9c2f2a Rosa’s story is quintessentially Canadian and as much an eruption as a creation, the prose thrumming so persistently as to appear organic, a sure indicator of the attention-to-detail beneath the novel’s surface. “Canadians love stories. If they didn’t tell them, there wouldn’t be a Canada today” a character notes in Dupont’s 2019-Giller-Prize-winning novel Songs for the Cold of Heart (also translated by McCambridge). In some ways, it’s hard to imagine Rosa’s story being published internationally—it’s more Canadian than poutine with maple syrup; in other ways, it’s a story about reaching beyond familiar borders. Although it opens in Notre-Dame-du-Cachalot, a “hamlet at the end of the world, a tiny village forgotten by God and all of humankind” on the Gaspé Peninsula, Rosa has a “long life ahead of her, a very long life indeed”, and her vistas broaden. In just a few chapters, she will “absorb every detail of Boulevard Saint-Laurent, her eyes like Champollion’s deciphering the dust-covered inscriptions of the Rosetta Stone.” Dupont describes Montréal’s Saint-Laurent as “a swarming, bustling museum of every luxury and hardship, every language and colour, every sorrow and enchantment”, evoking Canadian writer Gabrielle Roy’s 1983 autobiography La Detresse et l'enchantement—translated into English as Sorrow and Enchantment by Patricia Claxton. Roy is sometimes presented as a Québécoise author for her renowned depictions of Montreal, sometimes presented as a Manitoban author because she was born in St. Boniface (now part of Winnipeg). Two characters in Rosa’s Very Own Personal Revolution discuss whether to represent a particular woman as “an Ontarian or Manitoban who married a Québécois” and debate the merits of descriptors like ‘French-Canadian’ and ‘Québécois’ (deemed preferable). One woman adopts a “CBC accent” to represent an English-Canadian perspective on the “allegory of Canada’s two solitudes” and advice on “reappropriating an insult with a postmodern twist.” Just as Rosa’s world expands in Montreal, so does her palate. The $500 monthly rent for her room includes “two balanced meals that Jeanne prepared herself, drawing on Canada’s Food Guide and Enjoying the Art of Canadian Cooking by Jehane Benoit.” Madame Benoit brought French-Canadian (ahem, Québécois) recipes onto the tables of English Canadians nationwide, and Rosa’s response is profound: “It was the most exquisite meal of her life. And she would spend the rest of her days trying to repeat the experience.” In the expanse of Rosa’s life, however, Eric Dupont focuses on her youthful discoveries, possibilities, and transformations—a quiet revolution (Révolution tranquille being a term used to describe the rapid cultural change in Quebec in the 1960s). With music, for instance, she “wondered how the same song could pass from the sun to the moon from one mouth to the next, how the same words, robbed of all meaning, could either light up or devour the soul. Something in the voices touched her in a place where she hadn’t been touched often enough.” This story of personal revolution is political, too, which is true of Dupont’s fiction generally: playfully but persistently. Life in the Court of Matane (McCambridge’s translation of Dupont’s 2008 novel, Bestiaire) opens with a young character named Eric marvelling at Nadia Comăneci’s Olympic performance. Her “grace and beauty” and, later a dance recital by Laotian performers, leads him to wonder: “Did communism make people more graceful? The idea seemed to have some merit.” Rosa’s mother is “a fair-to-middling trade unionist, a socialist, and a first-rate Scrabble player,” so Rosa’s inheritance is political from the moment of her birth, words studiously arranged for maximum scores. Questions of ideology and identity riddle the novel, but they do not offer simple solutions: “When a girl from the Gaspé Peninsula realizes that she no longer even understands how snow falls, all she can do is cry. Because at that point, she no longer understands anything. Not a thing.” The female characters in Dupont’s fiction are fully realised, as complex as the elements that flavour Rosa’s landlady’s cooking. Even serious subjects are consistently entertaining in the context of Rosa’s story. Dupont’s humour is full-hearted and sharp-tongued; if the Leacock Awards didn’t favour short books, he’d’ve snagged one in every year he’s published. A scholar, for instance, might speak of tensions between rural and urban spheres in Canada, but Dupont writes: “In the village, pronouncing one’s Ks was associated with Montreal, and therefore with treachery and perdition. Though the odd little habit gave the villagers a sense of belonging to the bleak and hostile Gaspé Peninsula, more than anything it left others wondering why they seemed to have a permanent cold.” The comic potential in the melodramatic phrase “treachery and perdition” that describes this “odd little habit” might provoke a gentle smile. Dupont, however, channels the disdain of the habitually offended and creates rich scenes that culminate in sentences like this: “Here in Gguebegg, we dry the dishes. We don’t leave them to dry on the ggounter, ligge they do in Ontario!” (I do, in fact, leave my dishes to dry on the counter; I am chagrined.) Dupont’s books do invite soft chuckles, but they also provoke real laughter. (And they have encouraged me to, occasionally, towel dry a dish.) Coming-of-age and self-discovery, belonging and community: these themes dance on the page of Dupont’s novel like tiny gymnasts. When two Russian girls are chatting in Rosa’s Very Own Personal Revolution, one says: “I can’t alter the future any more than you can swap the last page of a book for another because you don’t like the ending.” But Dupont? He alters their futures, and he alters the course of French-Canadian and Québecois and English-Canadian and Ontarian and Manitoban and flat-out Canadian literature too. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|