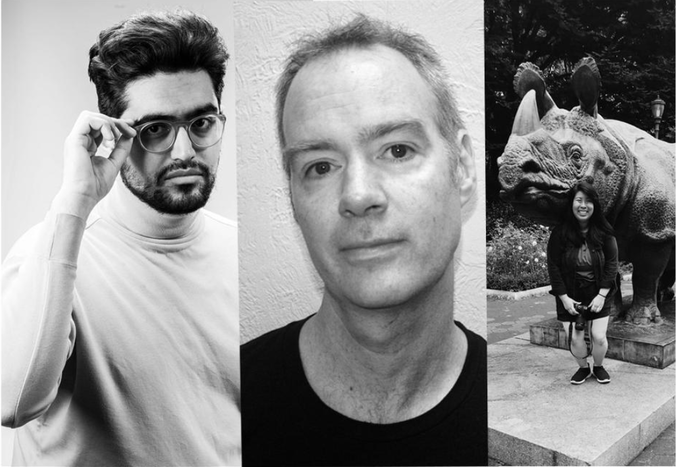

Interviews with Khashayar Mohammadi, John Wall Barger, and Tina DoInterviews conducted by Kevin Andrew Heslop and transcribed by Aidan Clark

|

|

A Djinneology of Rumi

By Khashayar Mohammadi for Christina Baillie “he knew that he was contending against a Deev, and he put forth all his strength, but the Deev was mightier than he, and overcame him, and crushed him under his hands.” - Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, translated by Helen Zimmern Rumi says to leave behind all earthly possessions to become Divaneh, to act like a Deev Deev from Da’eva through Avestan but Da’eva makes Devil through the indo-european connection neurodiversity fallen into predicament at the hands of etymology Divaneh now translated as crazy from old Swedish Krasa to crush, shatter jagged edges of a collective consciousness once prevalent now too sharp to fit into any rounded conversation but there’s a second etymology that says Deev through Deva Deva makes Divine Rumi says “Divaneh Sho” translated as “Become mad!” or is it to become Divine perhaps? to be touched transcendent gifted Deev now chiefly translated to Demon (through Greek Daemon) originally benevolent semi-holy dysphemised by history crazy when translated back to Persian becomes Majnun Possessed by a Djinn connected to Genius the Roman appropriation of Daemon e.g. Socrates had a Daemon Da Vinci had a Genius Djinns promised real by the Qur’an have become B-movie tropes now e.g. young girl moves to rural town her dorm room possessed by a Djinn a Djinn she can now carry like a venereal disease she can become Djinn-deh a “Prostitute” literally Djinn-giver but Majnun is synonymous with tragic obsession (Love) the Persian Romeo at the end of his wits driven to Poetry by love roaming the desert so long parents have given up hope Majnun possessed not functioning fragmented, but whole in eternal exile prone to ventriloquy {often called schizophrenia} wearing a thick layer of dusk as eye shadow and sailing the choppy waters of taxi window blinds staring at corporation names mowed into slanted, footlit grass staring out the window and into the mind the sheer effort of existence scratched onto the spine roaming the concrete deserts of indifference days dictated by pharmaceuticals now… ask me again about etymology: Deev <= Da’eva => Devil or Deev <= Deva => Divine Before we venture into your astonishing poem, “A Djinneology of Rumi,” published in issue ten of The /temz/ Review, I thought we might linger over its dedication “for Christina Baillie” and then its epigraph. We’ve spoken about the Baillie sisters before and the significance for you of Sister Language, an epistolary work which Gary Barwin has described as an “an ode to relationship, understanding, communication, love and trust as well as the possibilities and negotiations of disability, sisterhood and a life lived through language,” “a story of what happens,” writes Kyo Maclear, “when ‘everyday’ language mutinies and shatters, leaving a fragile chimaera of coherence.” I wonder whether you’d say a few words about why Sister Language is so dear a text to you and why you wished to dedicate this poem to one of its co-authors, Christina Baillie. I first met Martha Baillie in the Knife Fork Book Artscape location one day: this figure walked up the stairs--this lady with silver hair--who went straight to Kirby. They spoke in the corner and there was a very heavy, heavy atmosphere that, at first, I didn’t understand; but it later became apparent that it was very, very close after the suicide of Christina Baillie and Martha had shown up, spoken to Kirby and had left a couple copies of the book. This happened around 4 PM and she returned for an event at 7 PM the same night. In that three hour period between, there was miraculously no—absolutely no--foot traffic, which provided just enough time for me to read the book cover to cover. Mm. A book that was not for sale or anything--it was just a book left for Kirby. And I read it cover to cover. It provided me with so much new language to speak of all my experiences as a psychotic, which, I also have to say: none of it has been at all even close to what Christina has gone through. I don’t have a syndrome; I had an onset that curved very well and it never happened again--and I have had less than a half-dozen psychotic episodes in my life. But, basically, Martha came back at 7 PM for that reading and we spoke about Christina, we spoke about psychosis, about how much it meant to me, and thus began this sort of, you know, posthumous relationship between me and Christina. That book really unlocked a new path in my mind, in my vocabulary to express things that I never thought could be conveyed about such a linguistically-defying ailment. Mm. I think about the epistolary nature of that book and of your collaborative work with our beloved mutual friend Entity (labelled Roxanna Bennett) and the luminary Klara du Plessis, with whom you have, respectively, a forthcoming chapbook (Unbecoming Prophecy from Collusion Books in May) and a full-length collection (from Palimpsest Press next year, [2023]). And I wonder whether you would say a few words about those collaborations, perhaps in relation to the significance for you of Sister Language, of the madness/divinity etymology addressed in this poem, and epistolary collaboration in general. What has it meant to you to write those books of back-and-forth poems at each other? Well, the epistolary format for poetry is a very powerful format because you usually write—you, as in, the proverbial—the metaphorical—poet—writes a poem into this nebulous abyss that will inevitably form an audience or an other. You’re never sure who will hear this and who will like this, but when you write poems to someone, you already know who you’re speaking to, so it removes that layer of audience-speculation--at least, the primary audience-speculation. Of course, it will have a secondary audience that will later read it, but your primary audience is very clear, the ‘who’ you’re speaking to in that epistolary format. I’m not quite sure if I have anything to say about the relationship of the epistolary format to madness. I prefer to be introspective with my psychosis. Mm. And speak to myself. Mm. I mean, me and Roxanna have spoken about how—have written a lot of poems to each other; but, it has mostly been—even though it has very vaguely veiled through disability--we’re basically speaking about our daily lives. It’s considered like a prerequisite that we know this about each other and we’re just speaking to each other as, you know, friends. Yup. As opposed to when I write, for example, “Djinneology of Rumi,” I am writing basically to someone who may not know what is happening here. Mm. There’s a layer of explanation that doesn’t really exist between me and Roxanna or between me and Klara because the whole exchange is centered around the searching and mutual understanding—in different scopes in each project, but--basically we don’t explain much to each other in those epistolary formats, while I feel like in certain poems that I write I think I’m explaining a lot. Mm. And there’s no value-judgements made here as to which is better. Both will find their own audiences. So, before we look at the poem proper, I wonder if you’d say a word about the significance of this quotation from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (via Helen Zimmern), which serves as the poem’s epigraph: “he knew that he was contending against a Deev, and he put forth all his strength, but the Deev was mightier than he, and overcame him, and crushed him under his hands.” I will be one-hundred-percent honest with you: that quotation is not a part of the Shahnameh that I immediately know or immediately knew. That was just to demonstrate a character of the Deev as a troll or a demon in Persian mythology. Mm. And it had nothing to do with how I connected to that piece. I basically looked for uses of the Deev as the demonic—As a mythological demon. It was just a simple showcasing of how it was historically used as opposed to how I personally connect to that. It was a simple search made to find a piece of the Shahnameh where the word Deev was used in that way, and not specifically a translation that used it the same way that I wanted to use it, which was as a pre-Islamic use of the word Deev in a negative connotation that did not exist in the prior version of the Farsi. This is, perhaps, one of the last uses of the word Deev and how it carried through contemporary Farsi-- Mhmm. —for the last eleven hundred years; and it is a use of the word Deev that is antithetical to how it was used in middle and ancient Persia. Excellent. So, to the poem itself, then: in broad strokes, we have a kind of etymology exploded, with stanzas sprung from cognates. And I wonder whether you’d tell me a little about how this poem came about, for you, and how you found your way to Rumi. Well, one of the most quoted lines from Rumi in the Farsi-speaking world is a line that goes: حيلت رها کن عاشقا ديوانه شو ديوانه شو و اندر دل آتش درآ پروانه شو پروانه شو [Leave away the deceits oh lovers become mad become mad Enter in the middle of fire become moth become moth] It basically says, Let go of this and that: become demonic. It has always been in my mind as crazy because that’s how it’s used in Farsi. A good friend of Christina Baillie was the first person who pointed me towards a very interesting etymology of Deev. I was speaking to Christina and Martha Baillie’s good friend, Ralph Collettee, and I was about to say Deev means—Deev comes from—and he interrupted me and said, Da’eva. That was his conception. I thought to myself, Oh, wait, wait--Da’eva: that is way too close for this to be a coincidence; so I went and looked into it. And, for me, Deev comes from Ancient Persian—an Indo-European language. But being an Indo-European language it must have a connection to Da’eva, which is originally Sanskrit. That conflicting etymology basically kickstarted this whole bifurcating etymology between divinity and a demonic power. Mm. Perhaps my favourite passage in the poem is the elaboration of the word Majnun with the phrase “prone to ventriloquy / [often called schizophrenia]”. And it’s here that the connection with the word ‘genius’ is made: I’m thinking of Michelangelo saying, My Lord, free my from myself so I can please you; and of the near ubiquity among artists of the sensation of the very best of the work they produce having come through them rather than from them. And I wonder if you’d say a word or two about genius, madness, ventriloquy—how these relate to schizophrenia and this bifurcated etymology that you track in the poem? There are some disputes on whether or not Djinn and Majnun are actually related to genius or not. Mm. It has very perfect parallels in English, because, you know, Shaitan in the Quran is a Djinn and Djinns are fire-animals—fire-demons, they consider themselves—that are emissaries, basically. And, in the Bible, there’s Lucifer, from lux, as in, he who transfers fire, or he who transfers lights. Shaitan was a Djinn. I’m getting a little lost here. Genius, ventriloquy, schizophrenia. It’s a very multi-faceted thing, the idea of becoming possessed. This literally comes from the word Djinn. The idea of becoming possessed, the idea of becoming crazy, the idea of becoming in love, and the idea of having faith—these are all words that are so intertwined in the Farsi language. A lot of the second meanings of these words comes from the Sufi uses of them. Mm. In contemporary Islamic society, an orthodox muslim will consider a person of Sufi faith an infidel, basically. Mm. They’re not considered muslims. There are these Persianate introductions of philosophy into Islamic philosophy that become very common in the entire SWANA-region, because of the Farsi—Persian—becoming a liturgical, legal, and trade-related language, and becoming very wide-spread. I think I’m explaining things that have nothing to do with what you asked. This poem itself is sort of implicitly tangential--by exploding an etymology, it refuses linear time--so you’re right on topic. I do have another question: I was reading this poem this morning with a friend who remarked on the tercet towards the end of the poem-- The what? The three-line stanza. Yes. Which goes “now … / ask me again / about etymology.” And this friend of mine remarked that it’s phrased as a kind of challenge. They were wondering about the significance of that tone--whether the poem was written in response response to a repetitive query. Well, it goes back to the cyclical nature of it, because the whole poem explains how it has gone and come back as something else. Mm. I mean, there are examples in English that—Perhaps they don’t span, like, thousands of years, but, for example, one of my favourite cyclical etymological changes in English is the word venereal. Mhmm? Used as all things related to Venus, then after being used so commonly with venereal disease that when astronomers began speaking about Venus, they started using ‘Venutian’, even though it is not technically correct: they started using ‘Venutian’ just to separate from the sexually transmitted disease part of the word venereal. Amazing. I think there’s a lot of elitism towards what words are used—what words truly mean, and, considering them as true, as the real meaning of a word and completely forgetting that the use of a word is as important as its intent, because that’s how meanings are made. Mm. A lot of people in linguistics tend to have this—not a lot of people in linguistics, a lot of people interested in linguistics tend to have this--zeal towards defining things based on historical context and forgetting about the intent of the use of vernacular and how it’s used on day-to-day basis. How we use it on a day-to-day basis is how it will be defined very soon after. Mm. That challenge is just to be aware of the flexibilities of language and, basically: keep an open mind about how language can develop. * * *

Resurrection Fail By John Wall Barger I've heard people say that when we die we will surely have a heart-to-heart with Christ. Wouldn't that be nice? I'd ask him, Why let my grandpa, when his mind scattered in the winds, wander the Bronx in his pajamas that day, he who like a cat was most afraid of indignity? I'd ask, Is it a joke to yoke us one to another with love just to yank us apart, like parodies of the sacred? I'd definitely ask about Muhammad Niaz. Christ might try to interject but I'll be on a roll. You probably recall, Christ, I'd say, that "mystic" in Pakistan named Sabir, bored by the same old miracles, who told the crowd in a little square he could reanimate the dead. All he needed was a volunteer, someone who'd like to experience the afterlife and come back. Niaz stepped out. Niaz was perfect: forty, day laborer, wife, six kids. He didn't want to leave this world, at all. He believed. Sabir led Niaz to a table, tied his hands and legs with rope, and cut his throat. Christ might say, Is that a question? Christ, the corpse of Niaz is your corpse. We the children of Niaz no longer want you to come back. We have made a heaven of corpses here on earth. Hands clasped in reverence for what we see. Soaked in the rain of it. John, I wonder how the concept of “Resurrection Fail” came about for you, how it sort of germinated, and how you came to write a collection containing four different poems so-titled. The story I refer to in the first “Resurrection Fail” poem is true, and came from an article that I ran across. I think you’re this way, too, right? Poems end up coming from a lot of found things—a lot of articles and random things people say to me. We’re part of a literary or world conversation with all these people and all these great words we read. I’m trying to remember where I came across the phrase "resurrection fail" first, but I think it was in an article about Muhammed Niaz, his getting murdered by Sabir. I had been writing a lot of poems involving resurrection. Mm. I wrote a poem about Charlie Chaplin (which is not in this book). Do you know the word resurrectionist? Mm. A resurrectionist is—what do you call them?—a coffin thief, a graverobber. Right. Apparently Charlie Chaplin’s body was stolen, and the resurrectionist tried to extort the family of Charlie Chaplin for his body. So, I have a poem about this resurrectionist with “grog-blossoms on his cheek,” who is dancing with the corpse. I love the term resurrectionist and I love it when there’s an extreme balance of sacred and profane. And all the better when there’s humor in it. I admit that this is a “grand”—that is, somewhat humorless—title, Resurrection Fail. I have another poem called “Resurrection Pie,” which is a type of pie that’s made from other pies. *laughter* So, that first poem that you mentioned is a sort of reckoning with Christ: Why would you allow, the ostensibly autobiographical narrator asks, my grandpa, “his mind / scattered in the winds, [to] wander the Bronx"? And why would you give us loved ones only to take them away?And then the main of the poem focuses on this instance of a believer who lets himself be killed. I wonder if you’d say a few more words about feeling compelled to write particularly about this story of Muhamed Niaz and his sort of willing martyrdom in the context of this poem. I guess there’s a kind of a dramatic irony there. The speaker—who knows what happened, and can comment on the events from a great distance—is looking on it and Niaz. The world is full of believers and, to me, that’s a sympathetic kind of thing. I’m sympathetic to people who believe in things, even if those things seem superstitious to me personally. Maybe it’s a response to the Gen-X nihilism and godlessness I grew up around. I even begrudgingly admire the completely irrational anti-vaxxers here in the States. You’re American, aren’t you, or partly American? No, no, no. Oh. I thought you said so in the book at one point—or somewhere. I made all sorts of shit up in that book. *laughs* I’ve never been to Italy either, but— Oh, you haven’t? *chuckling* Oh, I was convinced by that one! Hm. Well. So I do feel sympathy for believers. Mhm. I feel sympathy for folks, especially here in the States. I’m not a Christian, and I find the anti-vaxxers kind of unappealing. But I feel like what gets them there, their belief system, is kind of admirable, or tragically noble. I wish that I had more of that myself. Mm. And I don’t mean that in a condescending way. I really admire it, though I can’t quite get there myself, if you know what I mean. Totally. I don’t know if this is a roundabout way of answering your question. This first “Resurrection Fail” poem came from a dive that I was doing for a few years into the Darwin Awards. I have a bunch of Darwin Award poems where I attempt to strike a more “funny” balance than I achieved in this poem. Right. This poem is not too funny but I think there are poems in this book where I strike a more humorous balance, I hope. This first poem, which is so self-serious, comes from my thinking about resurrection and religion and death through a lens that is less serious. Because there’s a godliness to humour, I guess--something divine about bellylaughs and involuntary urination. Sounds like rapture to me. Yeah, exactly! I think I get caught up maybe or a little self-conscious about how much loss and grief and how much suicide and things like that there are in my book. They’re not suicidal ideations on my part, but all these people who I know who have died in these various ways and all the loss in my life got collected in this book. I ran into a friend the other day who said, "John! I love Resurrection Fail and I’ve been showing it to all my friends. It’s your funniest book.” I was like, “Really!? Oh, wow! Okay. I didn’t really think of it as funny." Resurrection Fail By John Wall Barger “The Moon over Auschwitz” was the original title of this poem. I stared at it so long I lost track of what that moon shone upon. I thought, I can’t write that, I’m not Jewish, I’ve never even been to Poland. I did not mean harm. Moon can mean sorrow: as in, I read how the dark side of the moon is actually turquoise which glows like ice over the barracks of Birkenau. Now you are googling me to confirm that I am, as you guessed, a white dude. You doubt that bad things have happened to me. I doubt it, too. So many bad poems are litanies of personal trauma peppered with trope, one would think stepping into daylight is enough to horrify us all, but isn’t it? How different is the Auschwitz moon from the moon over Philadelphia? Each drifts over us like a clod washed away by the sea. I did walk the Villa Medici in moonglow between goddess statues which like clouds have no face. Or is that La Dolce Vita, or The Tale of Zatoichi? Yes it’s the blind swordsman Zatoichi touching the lovely face of the sister of a yakuza. They are falling in love. Zatoichi’s fingers in the language of movies are aspects of the moon. Have you ever seen the moon on a sunny afternoon out of nowhere? Like a watermark in the desert, like a thin man I washed dishes with who kept taking breaks to read Phillis Wheatley. When you’re drowsy or stoned, when you’re really not looking–– then the moon comes, its kidskin grin, the Padre Pio cuts in each of its palms, while far below down here fire rises upwards water flows downwards love spirals outwards and hour after hour we carry our dead out of its light like ants. Mm. The only way to persist through grief, I guess, is humour. So to have both in the same book feels natural. Um, the second “Resurrection Fail,” with a gorgeous line “the dark / side of the moon / is actually turquoise / which glows like ice / over the barracks / of Birkenau,” meditates on the in/appropriateness of a white dude invoking Auschwitz. But then we get the reference to Donne: “How different / is the Auschwitz moon / from the moon over / Philadelphia? Each drifts over us / like a clod washed away / by the sea.” So, given that we live in the era of identity politics--which seems to me to mean a kind of fetishization of our differences rather than an admission of the profound density of our interconnectedness--I wonder whether you’d say a few words about this move, about this reference to Donne, its significance for you, and how you think about the possibility of innate human solidarity in the face of suffering regardless of cast or creed. Okay, first of all, there’s no answer which is gonna live up to that question. *chuckling* Too good of a question! I think that’s “No man is an island”? Right. “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” “It tolls for thee.” Is it a cop-out if I pull it up on my computer? Not at all. “If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less.” That’s it. That’s what I wanted to rub in there: “Each man’s death diminishes me, / For I am involved in mankind.” Mm. You’re not gonna trick me into interpreting my own poems, are you? I’m not capable of tricking you; you’re only capable of tricking yourself. You’re tricking me again! *chuckles* I’ll say this: I like the rub of the clod and the association with “Each man’s death diminishes me, / For I am involved in mankind.” And for good reason I couldn’t quote those later lines; but I wanted the smell of those lines from Donne to be associated with my moon poem. Why the hesitation to quote the latter line directly? Is that too on the nose? Yeah, too on the nose. And let me just say, I was quite self-conscious about mentioning Auschwitz and Birkenau. I really wondered about it to myself; and my editor gave it a pass. But I wondered to myself, as one should, I hope, why is it alright? And what I came to was that even during the worst horrendous things that have happened in this world, the moon is shining. The moon is shining on all of us. It was shining on the terrible Holocaust and it’s shining on us here in Philadelphia and it’s shining on London, Ontario. I meant it as a natural event that draws us together. Quite true. So, you’ve lived in Nova Scotia, Italy, Ireland, Finland, Hong Kong, India, and, now, Philadelphia; and I wonder: to what extent do you feel like travel and exposure to different ways of being from the one into which one is born has been necessary to develop the kind of empathy this “Resurrection Fail” poem proposes? Do you feel like travel has broadened you? I’m not positive how to apply that to my moon poem, but I can respond in a more general way. Sure. I was kind of a privileged fuck when I was twenty years old. I had very little sense of how lucky I was to not worry about money. I mean, we were very middle class; my parents were kind of educated hippies; I didn’t think too much about money. And, you know, being a white dude, too, doors open to you and you’re not even aware that they’re opening to you. Right. But I was aware that to be an artist--which I wanted to be--I needed to go through difficult stuff. Mm. So, one way that I did that—put myself through difficult stuff—was with relationships. I got into a lot of relationships with women and that put me through the wringer. I had a heartbreaking marriage in my twenties. And I had some relationships after that where I really suffered. And I found some experience through these relationships. Mm. And in a way that suffering from those relationships helped me develop as a person and to get some perspective, which I didn’t have as a young adult. The other thing I’ve done, to gather experience, is travel. Right. I mean, I’m not going to claim too much self-awareness. But, in gathering what little scant bits that I have, travel has helped. You are right that this poem does try to scan the world, and provide a big scope. And I was in Italy for a while, so that part is kind of true, and the part about washing dishes is a reference to a restaurant where I worked in Dublin, Ireland, so yeah the worldview that I’m trying for in this poem is informed by fragments of travel. Resurrection Fail By John Wall Barger At a street vendor in Hong Kong in the smoke of chestnuts came a vision: the very last time with Inge my erection a wound in the air in our tiny flat in Rome. Not having touched in months What are you doing, touching yourself? she asked. Maybe, I said. Well all right, she said. I kneeled between her legs and she who once saw a gentleness in me raised herself to my hips so I saw her again with all her faces at once like a village, the villagers walking out to the night forest bearing the beloved in their arms the one who would die that night. They circled the beloved singing the oldest songs with full hearts and when at last those eyes fluttered shut, the sun came bearing the slightest warmth. The third Resurrection Fail poem, beginning with “At a street vendor in Hong Kong / in the smoke of chestnuts / came a vision:" puts one in mind of Vijay Seshadri who writes that your poems “begin easily in comfort and quotidian intimacy’ and end just as easily in surprise and wonder and amazement.” This reminds me of Billy Collins’ statement that poems begin in Kansas and end in Oz. Does this structure from Kansas to Oz--or, in a maybe more Whitmanian sense of looking at the saltshaker on the table, say, until it becomes full of stars--resonate with your sense of your own work as a poet? I wonder whether you’d say a word about what we might think of as your poetics, about beginnings and about discovery. Well, I find narrative poems hard to write. I write a lot of very banal narrative drafts of poems. I walked to school today down Walnut Street here in Philadelphia, and there’s a Michael Jackson impersonator at Rittenhouse Square who dances. But if I write a poem about walking down Walnut and seeing a Michael Jackson impersonator, is that a poem? It feels like something is happening but not enough. You know that feeling, right? It’s a stanza. Yeah! So maybe I’m a narrative thinker. I’ll write a poem that’s very narrative and then I realize something has to happen here. Part of my process is that I have this boneyard of just endless--mostly detritus from other poems, or fragments from books I like--lines to possibly use in poems. Gold, in other words, like ‘a clod be washed away by the sea.’ Just stuff that I found. Everything by Cormac McCarthy is in there—back up the dump truck. And phrases: De Profundus—what a great phrase! Throw that in there! Mm. So, I have the Michael Jackson impersonator and me walking and De Profundus and something by Comac McCarthy and then I’ll come in with my little screwdriver and I’m like, How does that and that hinge together? Do you ever have this experience? We’re are making these leaps in our poems: some fall flat, and some of them are like magic. For me, sometimes they connect and I don’t know how they connect, but they do. Mm. And nine out of ten do not work, in my case. But then sometimes I ask myself, What is the connection between being in Hong Kong and the chestnuts and then this allegorical village? I have a narrative poem, essentially, but something's got to happen. Like you said: Oz. And then I just keep pecking at it until I’m satisfied--until it’s weird enough. I just keep pecking and pecking and pecking and pecking. So, on this point of palpable connections between things that seem too disparate on their faces to be connected, I was listening to a reading and sort of Q&A with Randy Lundy a few days ago and he was like, Metaphor doesn’t make connections; it reveals connections: metaphor reveals the density of interconnectedness of reality and it is a reminder—sometimes a startling reminder--of how densely interconnected everything is. Amazing. Which resonates, yeah? Yes. But who is Randy Lundy? Yeah: Cree, Irish, Norwegian poet; Barren Lands First Nation; he’s gotta be in his mid-fifties; University of Regina Press put out his most recent collection, Field Notes for the Self. Superb. I ordered a copy and it made me want to ask him—as I want to ask you now--about your sense of the relationship between poetry and dreams and how the immediacy of metaphor connecting things that seem completely separate in dreams makes sense? There’s something about these poems where, maybe as a result of the screwdriver you bring to the poem, it feels believable in the same way that one might say, It made sense in the dream. So, how do you think about dreaming and metaphor and their relation to your practice as a poet, John? What I want to do--and this is gonna sound, perhaps, super-ostentatious, but here goes--what I really wanna do is introduce a spiritual component to my poems, I think. We’re all trying to wake up in some way and especially in our corporate society. It seems ridiculous to say so but I think that’s what we’re all trying to do. That’s what we would like to do. And we don’t have language for it in this world. There are places where what I think of as spirituality and trying to become more immediate in our consciousness overlaps with my poetics. And I think one of them is what you’re talking about, what you’re hitting on, which is almost like a Zen koan. Zen koans have this kind of *snaps fingers* which makes this logical jump which is meant to surprise the listener into a kind of quick, heightened, awakened moment. And to me, that’s the same thing that happens with the kind of surprise—the leap--metaphors make. You know, the word metaphor means a jump: it’s a jumping-across. And that jump across is the same as monks who put sandals on their heads in Zen koans, which “awakens” the student-monk. So, for me, it’s a process of inviting the reader into the ecosystem of the poem. It’s like taking somebody's hand and pulling them into the foliage, which, like you say, is this liminal, dreamlike state. And the way, I think, our minds work--the way dream works--is one of the triggers which allows us to go there. So in my poems I try to create these elaborate entryways, which, I hope, are kind of inviting. It’s like--did you say Omaha and Oz? Kansas. Kansas. I feel like the Kansas of my poems are very, I hope, inviting. Maybe it’s a carnival entryway and the vibe is like, Come on in! It’s fine the air is great in here and everything’s great! And then once you’re in there it’s like, Holy fuck, there are mirrors and you’re all sideways and the reader is disoriented. The reader thinks, I thought this was gonna be fun. You promised me I’d be in Kansas. *laughs* So, once we poets are in this poem space, then the possibility of taking the reader into some kind of place where we can surprise them and they’re included is possible. But it’s a different mindset--which hopefully encourages us all to go through something, either to release something or, cathartically, to have a shared experience. I go through it and you, my reader, can be my proxy. There’s no invitation, then, without your having gone through the carnival yourself first, right? Exactly. Yeah: I’ve gotta see it: I’ve gotta see it all for the reader to see it. Resurrection Fail By John Wall Barger Strangers, I like how our fingers brush handing coins to and fro at the market. That communion. On this spot in the schoolyard during recess I walloped Bruce Church in the gut. I draw a slow smile from the tough old bird in a raincoat at the bus stop. I sit on a park bench in new moon dark. A crow in a black feather boa in streetlight shadows flirts with a dash of string. Bruce, I’m sorry. I was trying to impress a girl. I have more rage than I seem to. I doubt my heart. Love seems impossible, Bruce. Though we exist in its ripples. Like the anatomy student I once met who slid the sheet off a corpse and there was his childhood crush. Approaching a conclusion here—with great gratitude for your time—the fourth “Resurrection Fail” includes an apologetic recollection of having “walloped Bruce Church / in the gut,” and goes on to address Bruce directly. And this puts me in mind of another interesting moment in the poem “I Received a Bitter Email from a Good-Hearted Man,” which begins, “So twenty years of friendship / ended in a small gesture / like a door sliding shut …” And I think about Karl Ove Knausgaard and I think about autobiography and, presuming an autobiographical narrator in both cases, I think about how the published rendering of moments of one’s life takes on a kind of sacrosanctity, elevating memory to an authoritative account of a personal, sometimes shared, experience. And I wonder how you think about memory, especially about authority, as it relates to your work as a poet. Can I ask what sense you mean by authority? So, if we went to lunch and spoke for an hour and then both wrote poems about that experience, the poems would be significantly different. But because most of the people we encounter aren’t also writing a poem about it afterwards, there’s a way that what you’ve written and published becomes a definitive account. And so when I’m thinking of Knausgaard publishing these autobiographical novels, my understanding is that he was approached by members of his family, members of his community, people who were frustrated with his rendering of the story, because they’d say, That’s not how it happened and now it’s published and there are millions of people reading it. So I wonder about how you think about authority and an authoritative rendering, especially if those experiences have been shared with other people. I find, to begin with, that I use my poems to remember. It’s almost like having a photograph of something. There’s a picture of me with a frog when I was, like, two, and I can’t remember that frog in reality, but I remember it through the picture. You know what I mean? The picture becomes the memory. Mm. And I find that writing poems about particular events—like my ex-wife and I singing Tom Waits in the car, which is in my Resurrection Fail book—I worked on that poem so much that the neural pathway of the original memory has been preempted. Whatever that estuary was has become a river and the poem has taken over that memory. Mm. Mm. The poem about the friend sending me the letter, that’s a real friend break-up that I had. And, in a way—maybe I’m onto what you're saying, and maybe I’m not—I’m kind of claiming that break-up, by creating new neural pathways through the poem. I’m telling it in a kind of public way and taking that authority as my own. Mm. The poem is its own thing, right? The poem is not reality. The poem is happening in the theatre of the mind of the reader. It might be based on a neural pathway of mine or a photograph or something but the real, immediate action of a poem is in the theatre of the mind of the reader. That’s where the immediate, present-tense verb, the mercurial truth of it is happening. It’s not a description of some other event: that doesn’t matter. It’s just now in the mind of the reader. For me, everything I’m doing in a poem is trying to accentuate the experience—the immediate experience—of the reader, and to remove all of the reported information and distance of the original experience. I want to clear all that away and make it direct. I don’t know if that means borrowing a certain authority but it certainly means bending the truth a lot. In the same way that the estuary has to bend in order to give way to the river. Yeah. Amazing. Can I ask you a question? Yeah, please. I’d love to know your response to the authority issue. When writing’s going well it doesn’t feel so much like I’m generating the text but rather that the text is almost generating itself and I’m discovering it. It’s revealing itself to me. I think it’s probably not unlike the experience that painters have, for instance, if they’re possessed by some sort of inspiration. I don’t think of poets’ authority as being contained with individual circumference; I think it’s much more diffuse. And it has to do with all of your sense-impressions, all of your experiences, all of the events that have happened in your life, the way that your memory works, your hangups, the language itself freighted with all sorts of associations and all of that, like, blends. And so, in that sense, one is speaking on behalf of all their experiences, all of their communities, all the people that they’ve ever met; and, in that sense, authority is not anything like the distilled person-wearing-a-suit-and-tie; it’s vastly more diffuse. I love that. A lot of the poems in the correct fury are made up: I guess I draw bits from everywhere like everybody does—sometimes from film, sometimes other peoples’ experiences, sometimes conversation—and so authority doesn’t really have much to do with that. This next book that I’ve just finished is almost entirely comprised of dreams that I dictated in the middle of the night and then, the following day, sat down and typed and then, to the extent that I exerted any authority over the text, sequenced and sectioned. Probably over ninety percent, maybe ninety-four percent, of the text was transcribed verbatim. So, in that instance, wherein authority? And I suppose dreams, like poems, are that same kind of amalgam of everything that one has ever seen or felt or thought or heard. The authority ends up getting circumvented. I mean, Leonard Cohen said something like that when he was given an award for songwriting. He said, It’s great because we, who write these songs, we writers, don’t feel like the writing comes from us, but we’re glad that you think it does. *laughs loudly* But, it doesn’t. We don’t feel like it does. * * *

i tell my mother everything By Tina Do which is to say: I only tell her about the things that are safe-- yes mom, I got an A in English, no mom, I don’t look at boys, only textbooks of course, the haircut you gave me in front of the bathroom sink is fine I understand—I won’t go to the sleepover yes, it’s ok to sell the piano so we can pay rent-- mom, let me explain the movie-- this character lives, this one dies, this is how everything ends. or rather, this is how it begins: hey mom, I got a C+ in math to the surprise of my peers and loved a boy whose name was the same as a crowbar until he laughed in my face and called me ugly I wish we hadn’t sold the piano-- the one I cherished with all my fingers until I was 16 with a crack in the middle C key because I dropped the metronome on it trying to cheat the kitchen timer you set for two hours—but I was never going to be a concert pianist at least not the one you rented out to aunts and uncles who were never mine except in ways that didn’t matter paid in nothing but gummy smiles, sore cheeks, no boundaries and thêm một bài hát con-- I have never held a cigarette, but I want to know what it’s like to be a proper rebel—leather jacket, army boots, fishnets, and piercings, hold smoke in my lungs like I have something to prove. I shoplifted as a teenager because you couldn’t afford to buy yourself new underwear and pay for our groceries, so I stuffed panties into my coat sleeves and put them in your drawer. I guess I am saying I don’t know how to live like I’ve been loved my entire life that I only watch movies in short bursts pause after every twenty-minute interval pause yes, I’ll take you to the store / the doctor / the dentist / the post office pause knives is spelt with k / oh, it means the same as dao rewind mom, this is the story that bà nôi told me about you: a girl brings up four brothers for a mother that is there but not really leaves one continent for another to settle in uncertainty sews tapestries for a history that has chosen to write—her out— about the men who thought warfare was between a woman’s legs, then went home to their wives and loved their families-- all this to say: my mother doesn’t tell me about the dangerous things, that she ran with knives before she could spell them in English cut her hand on blades before she knew how to say blood, tries to cook bún bò huế with a half-formed tongue which is to say: this is how we live and die. this is how everything ends—lingchi Tina, I wonder whether you would say a word about two of the immediately apprehensible formal choices in the poem, namely, the smoothness of the transition from the title to the first stanza—"I tell my mother everything / which is to say:"--and the choice to use lower-case letters when beginning sentences throughout.

I wanted this poem to feel like a conversation, something akin to two people whispering secrets beneath blankets, or spoken in hushed tones in the dark. The transition from the title to the first stanza was sort of meant to mimic the beginning of a conversation, with the speaker getting straight into what it is they have to say. It mirrors the ways that I often speak to my parents, or rather, learned to speak to my parents—get to the point, say what you have to say and go from there. Logistically speaking, I also couldn’t imagine another title. I really like poems that use the title as the de facto first line, so that was also something that may have played a hand in that formal choice. As for the lower-case letters: a lot of the things that the speaker admits are things I haven’t said aloud, or imagine someone would not say aloud. For some reason, I think upper-case letters give off a firm and boisterous appearance (sometimes), so the choice to use lower-case letters was meant to quiet the piece down, make it feel a little more informal. I wonder whether you’d say a few words about the significance of the couplet-form and its relationality in the context of the poem’s subject matter. “I tell my mother everything” was actually the very first poem I wrote in this couplet form. In the earliest version of it, I think I put it into 3 or 4 stanzas. But I didn’t like the way it looked on the page; the poem didn’t really breathe the way I wanted it to. Couplets, to me, feel like two halves of one whole. They’re in an intimate relationship with one another —one line relies on another to sort of complete it. The poem, which revolves around this relationship between a mother and a daughter, is informed by my relationship with my mother, plays off this idea that one is incomplete without the other. There’s a co-dependency there, and I thought couplets was a fitting way to work through that relationship in the poem. Obviously, many of the lines do not end when the couplet is completed. So that enjambment, the ways in which certain things carry forward even when the line has technically and visually ended plays with that idea of us constantly holding the people that matter to us close by as we move through and navigate different situations in life. Another question on form: the em-dash is a favoured punctuation mark of yours--at least judging from this poem alone--and you also make use of indentation within lines. I wonder whether you’d say a few words about those two formal choices, what they afford. Em-dashes are just so visually stunning. I like that they can be used to mean nothing or mean everything. They add emphasis when you need them to, cause interruptions, can help expand a train of thought, can be deployed to work for you spatially, emotionally, to include something—or exclude something. You’re definitely right when you say it is a favoured punctuation mark of mine. I like the flexibility it affords and ways it can be used to say things in ways that matter and ways that don’t. Indenting within lines is really fun. Part of what made my degree so enjoyable was getting into the nitty gritty of a poem’s form—what the writer deployed from their arsenal to get their message across. I like the use of indents because they offer visual pause or breath to my writing. Sometimes it’s easier to breathe when there’s a very apparent reminder that you need to pause and stop. I notice the infinite sweetness of the eighth couplet ... with the crack in the middle C key because I dropped the metronome on it trying to cheat the kitchen timer // you set for two hours … … and the tenderness of this (presumably autobiographical) narrator towards the narrator’s mother. I wonder whether you would say a word or two about emotional force--and how poetry might serve as a craft by which to express that felt force--which might not be expressible in lived, daily life. Poetry has that ability to affect people. That line is definitely autobiographical. My mom used to set a kitchen timer to make me and my sister practice piano. She’d set it for like 90 minutes and we would have to plant ourselves on the bench and play until the timer went off. As we grew older, we realized that we could kind of “cheat” time by turning it in small intervals when my mom wasn’t looking so we wouldn’t have to play the full time she wanted us to. But one time, in my efforts to cheat the timer a lot, I ended up dropping the darn thing and it actually fell so hard that it chipped the middle C key. The absolutely amazing thing about poetry is that people don’t need to know the story of those lines to take the words and make of them what they will. Not everyone has broken the middle C key of their piano dropping a hen-shaped timer on it, but maybe some people have tried to trick their parents into believing they did something when they haven’t, and that ability to unite people with different experiences and views, and for poems to find people when they’re in need of certain words is nothing short of magic to me. There’s something about these lines … I guess I am saying I don’t know how to live like I’ve been loved my entire life that I only watch movies in short bursts pause after every twenty-minute interval ... that reminded me of something my brother was wise enough to point out, which was that: even the apparently unpleasant moments of interaction with another person you love, in retrospect, take on a kind of radiant abundance of longing and warmth--and these lines seem to crystalize or make-amber that sensation, suggesting perhaps that the narrator, after the inevitable loss of her mother, might pause movies every twenty minutes just to be comforted by that presence of memory. I wonder whether you would say a few words about that and how poetry can change a memory’s emotional timbre. Your brother is very wise! The line about watching movies in intervals is another autobiographical detail. My mom is a very chaotic viewer. She either asks a lot of questions or will watch a bit of a film and then skip forward, because she can’t wait. She wants the beginning and the ending, so she knows who has died, and who has lived. And it used to be a habit that annoyed the life out of me; watching anything with her was never ever peaceful. But that meant it was also never boring. So now that I’m older and my mom watches movies on her phone or with my dad, I do miss that chaos, and this was a nod to that. I think, given enough time and distance from any sort of unpleasant moment with a family member, everything becomes tinged in this sort of air of fondness and, like your brother said, warmth and longing. Poetry is kind of like a document that freezes a particular moment in time. So it gives you something to look back on, to remember fondly, or warmly, and gives you something to long for. I just want to tip my hat to the craft involved in the fifth-to-last stanza: leaves one continent for another to settle in uncertainty sews tapestries for a history that has chosen to write—her out-- about the men who thought warfare was between a woman’s legs … The sophistication of the layered sentences that you’re working with here as they expand through the couplet form is really something to behold. To turn that into a question, though, I wonder whether you’d comment on the maximization of meaning and how you’re overlapping sentences, deftly arranging syntax in such a way as to mean two or three or sometimes four things in a single line. This poem deals a little with this ambiguous understanding of history, or rather, the daughter’s understanding of her mother’s history and where she has come from, what she carries with her as she moves through the day, and how that might affect their relationship. But it also speaks to the ways in which I have noticed my family, and a lot of other families who look like mine, do not speak of the traumas or pains they faced in coming to the west, and also to the Vietnam War. All of that is intertwined for me. My mother’s immigration from Vietnam is tied to the war that occurred there, to the awful things that happened there and continue to happen in wars across the world. Her story is also tied to a history in which women of colour are typically excluded from, or at least a history in which they are spoken for and not given voices. I guess in these lines, I wanted to make that overlap clear—or, at least, clear to the people that are looking. In these lines, I think I’m the most deliberate about form and function. I wanted the em-dashes to close out “her”–an act of isolation and exclusion in the forms of grammar given to me to use by the powers that colonized my mother’s home country. The enjambment between the line about sewing tapestries and “the men who thought warfare was between a woman’s legs” makes it easier for the “her out” to be missed, or rushed through, because all we’re trying to do as readers is get to the main part of the line or sentence. I wonder whether you’d say a few words about the significance, for you, of the inclusion of what look to me like Vietnamese words throughout the poem, perhaps in the context of assimilating a poetic identity and what poetic identity in the context of bilingualism means for you, and how that synthesis has happened for you in your work as a poet over time. Part of my struggle in writing is that I always feel like I’m between two worlds. Like I’m straddling a line between two places that I cannot call my own, languages I should know and don’t, and languages I do know but shouldn’t. I felt guilty early on for excluding my native languages from my writing, but I also felt ashamed that for the most part, I cannot read or write in Vietnamese (which I typically speak with both of my parents), and Hokkien (which is what I speak to my mom in). When I began to include words from my mother tongue into my poetry, I would italicize them, and then add notes for translation at the end because I thought that was what you had to do as a writer; you make sure you leave the doors and windows open for your readers. They need to see everything and understand everything you’re doing. But I realized that that’s not really a sustainable thing. I can’t people-please my way through writing (as much as I want to try). I cried reading Ocean Vuong’s poetry because it was the first time I saw myself represented on the page. That mix of English and Vietnamese, and the tension between having to work through two languages to say what it was I wanted to say. So for me, being able to include parts of the languages I speak in my poems is me being honest with myself, and hopefully being honest with the people that come across whatever it is I have out there. I hope it helps them, like I was helped by others. |