Interview with Jen Sookfong LeeInterviewed by David Ly

|

First off, congratulations on your first-ever book of poems! How long has the idea of a poetry book been brewing for you, and how did the first few poems come to be?

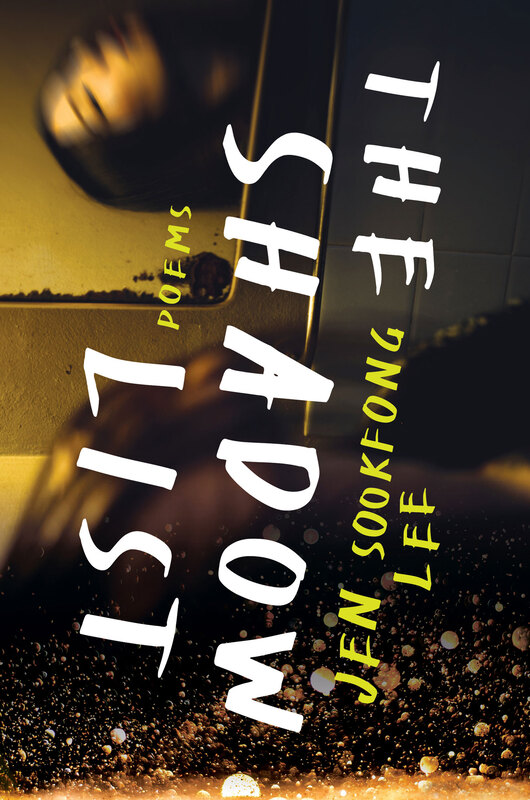

The collection had been building for six years or so. I hadn’t written poetry for 15 years, but I found myself resisting the idea of another novel, the writing of which can be exhausting and too immersive for comfort. Words are always leaking out of me, and it seemed like an organic step to try to write poetry again, just to see, and also so I could avoid another novel--haha. The first poems were really long and unwieldy, kind of like prose, but they also felt just right. And then I just kept writing. All of the poems in The Shadow List are written using the second-person point of view. Whether it was a conscious decision or not, what do you think the significance of this is for you? How is point of view for you different between writing fiction and poetry? As a fiction writer, I am used to writing about myself in ways that are obscured, or at least writing about experiences I am familiar with and padding them with fictional elements. As it turns out, with poetry, the way I manufacture that same distance is by using the second person. I am deeply uncomfortable with anyone knowing anything about me! What was the most difficult obstacle that you didn’t expect, but overcame, while creating your first poetry book? Honestly, and I will sound like a dingus, but line breaks almost destroyed me! I am terrible at line breaks and organization in poetry in general. The irony is that when I write or edit fiction, I am a master at structure! But put a poem in front of me and ask me to restructure it, and I swear my brain turns to glue. If it weren’t for Paul Vermeersch gently guiding me along, and showing me what was possible, my poems would all exist as word-filled blobs. How did you arrive at the title “The Shadow List”; what did you want it to encapsulate and convey? It’s from a line in one of the poems, “Wishes,” in which my narrator talks about what she most wants, and how she compiles a secret, or shadow, list of desires. I have always thought this book is about the urges women, especially racialized women with children, don’t ever express or indulge, and what happens when someone lets the gates open wide, and does everything she wants. The shadow list every woman keeps can be honest or bad or shocking or physical or anything. I wanted my readers to know that I see them and their obscured inner desires. Do you have any advice for fiction writers who want to try and write poetry? I know that I have an inferiority complex when it comes to poetry, meaning that I naturally write in ways that could be considered more prosaic, or that have a definite sense of narrative about them. I’m not someone who plays with the idea of poetics with a capital P! So I think, for fiction writers, just write poetry in the way you need to, in the way your voice chooses manipulates language. Don’t judge it by the standard of the most brilliant poet you love because comparison will paralyze you with fear. Just write it. Will there be more poetry books from you? If so, what do you think you’d want to explore through poetry? I think I will write another one, sometime in the future, although it probably won’t be for a while. I would really like to write a book of love poems, especially ones that are grounded in the settings I know so well around Vancouver. I have written a couple of sweet poems like that, but they didn’t belong in this deeply sad book! The last poem in the book, “Stigmata”, is such a perfect piece to close on: the narration of an experience with a palm reader. I read it as a “what is next?” for the narrator that we’ve been with throughout the book. In that vein, at the closing of this book, having journeyed with the narrator, what do you imagine happens for them after this book? My narrator struggles so viscerally with what she secretly wants and how she feels like she is supposed to perform. I would like to think that, afterward, she feels less divided, and that who she is in secret is one and the same with who she is in public. We talk about hybrid identities and genres all the live long day in literature, but what we forget is that hybridity suggests division and fractures, when in truth people and writing are whole beings and the only reason we describe them as polyglot is because the language fails. Diversity or multiplicity is a faulty concept. We just are, and our books just are. I would really love for my narrator to understand this and apply it to herself. Photo by Erin Flegg Photography

David Ly is the author of Mythical Man, which was shortlisted for a 2021 ReLit Poetry Award. David also wrote the chapbook Stubble Burn. His sophomore poetry collection, Dream of Me as Water, is forthcoming with Palimpsest Press/Anstruther Books in 2022. David is the Poetry Editor of This Magazine, part of the Anstruther Press Editorial Collective, and a Poetry Manuscript Consultant at SFU’s The Writers’ Studio.

|