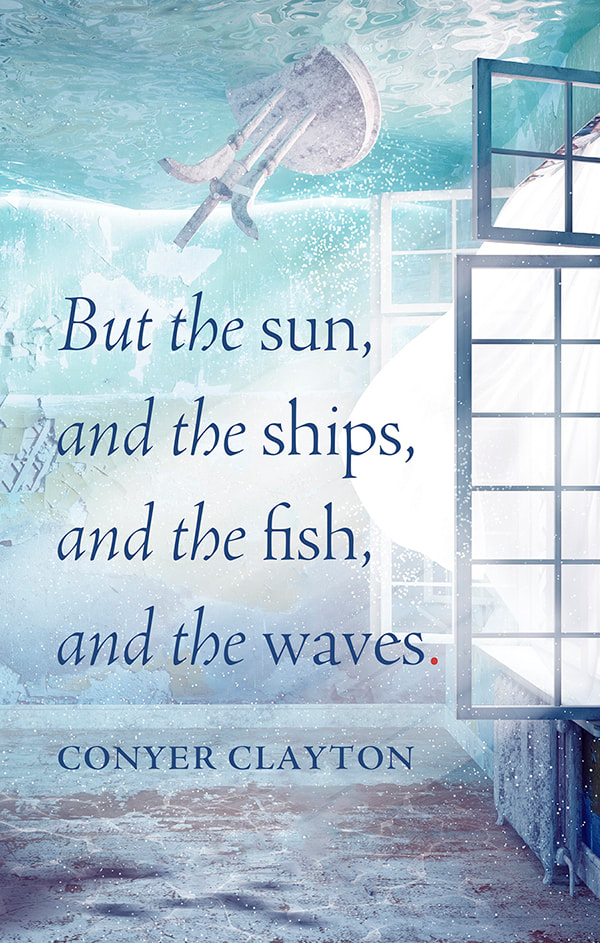

But the sun, and the ships, and the fish,

Reviewed by Carla Scarano D'Antonio

|

|

After her award-winning debut collection We Shed Our Skin Like Dynamite (2020), Conyer Clayton surprises us again with her collection of prose poems: But the Sun, and the Ships, and the Fish, and the Waves. Her pieces investigate what we feel and experience through the kaleidoscopic and unsettling view of dreams. The unconscious is at the fore and, from a surrealistic perspective, la vraie vie (true life) that relies on the subconscious and on dreams is more reliable than la vie réelle (real life), which is based on rational thought and social conventions, as André Breton claims in his Manifeste du Surréalisme (1924). Indeed, Clayton trusts her imagination and creates new unexpected settings and imageries that take the reader aback but also open them up to alternative ways of investigating past memories, relationships and roles in society.

Clayton has also published nine chapbooks, is a contributing editor to Arc Poetry Magazine and a freelance editor. She released a collaborative album with Nathanael Larochette in which poetry and music merge with fascinating results. She is interested in the intersection of music and poetry and her work consequently resounds with her multifaceted interests and commitments that encompass simple sounds, pieces of music, both instrumental and vocal, and words. Her vast production reflects her talents and diverse passions, and her work is widely published as well as publicised on her website, https://www.conyerclayton.com/ The title of her latest collection was inspired by the cover image, where water invades a room in a world suspended between experience and imagination, reality and dreams, and it is also the final line of ‘The Break’:

The repetitions emphasise the sense of mystery that is resolved in the dazzling final vision. What is experienced is a surreal reality in which the protagonist floats around while trying to find a route that is never certain, attempting to discover a more authentic vision and make sense of what has happened in her life or what is currently happening. The form of the prose poem has been defined by Clayton as ‘like a box’; it holds the pieces at the centre of the page. It looks tight and precise in a control of sorts that nevertheless allows openness at the sides of the page and freedom in the absence of line breaks and in the profusion of extraordinary images. Clayton has also remarked in one of her interviews that some of the pieces deal with CPTSD, complex post-traumatic stress disorder, that is, with memories of fear, abuse, assault, violence and loss. The aquatic settings therefore create an ambiance in which the protagonist navigates in the hope of making sense of and validating memories in a reconstruction of a self that has been disillusioned and probably damaged because of ill-treatment.

The storytelling is sometimes dark—the dreams look like nightmares experienced at the edge of insanity—but there is humour too and hope at times. The protagonist therefore faces a cruel, incomprehensible world; her female body, which is so vulnerable, flexible and solid, resists and survives in a transformation of sorts:

Various questions enter the mind. Is what we experience true? Are our memories reliable? Are dreams the essence of our being? Will we decipher what is happening around us eventually? The poems question the inner self and reveal provisional answers that do not solve problems but suggest different possible visions. The memories range from bereavement, a sense of loss due to disillusionment, failures in relationships, illnesses, death, childhood and traumatic memories of a girlhood in which desire and fears mingle in a complicity that leads to a route of self-discovery. Working through trauma and using writing as therapy is a way to read how the body reacts to different situations and is also a way to understand what occurs around us in relation to others. As Clayton remarks in one of her essays, she wishes to make soft something that is perceived as sharp. Therefore, the poet seems to suggest that what was once hard to experience and accept is now revisited in memories and poetry, transforming this circumstance into something milder and tolerable. It is a process that validates the individual and confirms their importance in a personal and unique way. It is a fulfilment that is never complete and is at the edge of the real and unreal, but nevertheless conveys understanding and authenticity.

Some lines are crossed out, such as ‘it was my fault’, ‘My dry bleached brain/held over a white bucket’ or ‘no one believes me’, as if to remind the reader of self-deprecating thoughts that enter the mind and victimise the self. Being a creative non-victim is what the poet strives for in an endless struggle in which the protagonist is a survivor. In this surviving process, the protagonist is located between the inside and the outside; she is committed to experiencing reality but is also attentive to her inner reactions:

The collection delves into a journey of self-discovery through the unconscious that implies dark memories but also hopeful moments expressed in rich imageries that open up the reader to mysterious and alternative realities. The protagonist is absorbed in a meandering tour that validates personal thoughts and inner feelings and where familiar and uncanny settings interweave. Poetry is the gateway through which to voice such an enthralling vision.

Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She obtained her Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing with Merit at Lancaster University in October 2012. Her pamphlet Negotiating Caponata was recently published by Dempsey & Windle (2020); she has also self-published a poetry pamphlet, A Winding Road (2011). She has published her work in various anthologies and magazines, and she has recently completed a PhD on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading. In 2016, she and Keith Lander won first prize in the Dryden Translation Competition with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems. She writes in English as a second language.

|