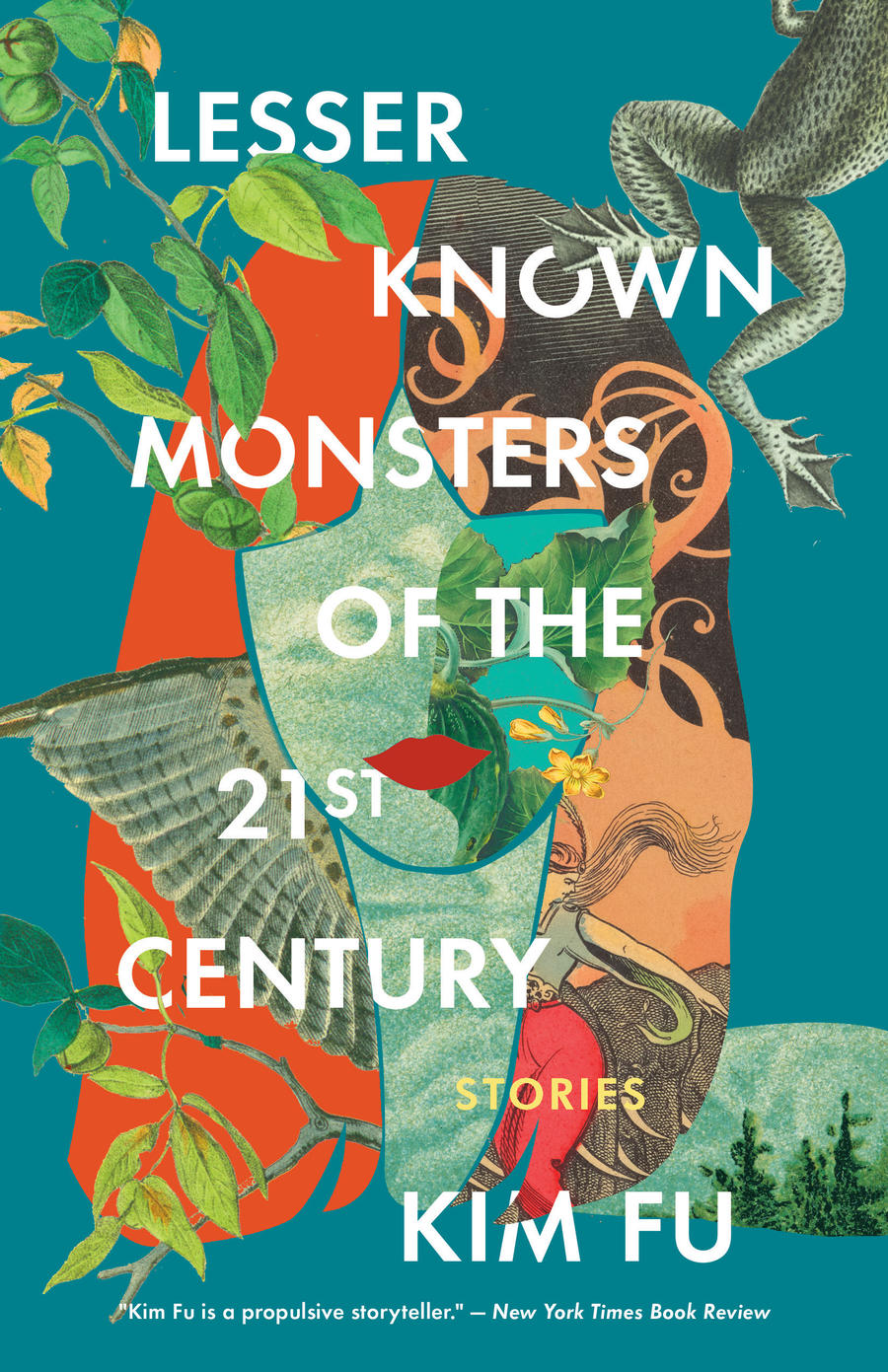

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century

Reviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

In Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century, Kim Fu examines the powerful precepts—love and loss, knowledge and belief—that simultaneously buoy and burden the stories’ protagonists, shaping and compelling their decision-making. Her fiction is nuanced and complex: a note of triumph can burst forth from chaos, a wisp of despair can tinge contentment, and memory can embellish reality.

In particular, Fu navigates the ever-shifting balance between vulnerability and power with finesse. She engages readers in the process of interrogating that relationship, via narratives that spiral around innocence and experience, scenes pierced by brutality and tenderness. Her first novel, When I Was a Boy (2014), opens with two boys armed with pieces of long, wild grass that leave welts on tender skin when whipped. One boy leaves the shape of an asterisk on the other boy’s skin, a crisscross pattern of pain. The main character, observing, takes note of the imprint on flesh, memorizing other patterns of masculinity and femininity alongside. That’s Peter, who thinks of his “body as a machine, a robot”, a thing apart, “nothing to do with [Peter].” In The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore (2018) Nita’s “body could do one task while her mind did several others” and she longs to “outsource eating and sleeping.” The visceral and instinctive are intertwined with the robotic and automatic: “A torrent of thought, of insight, was trapped inside the mechanical bend of bones, snap of tendons, fragile and unreliable and always, always slow.” Even an ordinary situation is constructed to cast a light on questions of agency, as when Isabel is described sitting near the door at a party: “Tiny, invisible, at risk of being trampled.” In Fu’s hands, the coming-of-age narrative slants towards a becoming-of-self story. As in Leone Ross’ Popisho (2021) and Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (2007; Trans. Deborah Smith, 2015), the natural world plays a pivotal role in self-discovery; as forested and watery borders ebb and flow, characters’ identities take shape, and when Fu queries broader concepts—like technology and progress—her intelligence and empathy are rooted in both character and story. There is room for wonder and awe in her short fiction; like Heather O’Neill, Anar Ali, and Nalo Hopkinson, Fu’s short-form and long-form writing embraces the ordinary and presses it into new patterns and arcs. Her characters’ lives are both banal and strange, monotonous and surprising. The settings in Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century are both familiar and fantastic; as in the linked stories in Christiane Vadnais’ Fauna (2018; Trans. Pablo Strauss, 2020) and novels like Thea Lim’s An Ocean of Minutes (2018) and Larissa Lai's The Tiger Flu (2018), Fu's worlds are recognizable and bizarre, gritty and shiny, metallic and plastic—both enduring and evolving. Whether at a funeral or on a hike, whether in a domestic or imagined space (a yard or a garage, with a simulation or with a sea monster), human responses are at the heart of these short stories: sometimes gentle, other times monstrous. These narratives refract off binaries but primarily unfold in the between spaces, both literally and metaphorically: “She let the lid settle over her. It didn’t close completely—a thin edge of light was visible in the space between the two halves.” This glimpse of light serves to balance the grime and torment, as in a story originally published in Room, for instance: “The realm of pretend had only just closed its doors to us, and light still leaked through around the edges. Everything was baffling and secretive then, especially our own bodies, sprouting all kinds of outgrowths that were meant to be hidden, desperately ignored and not discussed, hairs and lumps that could be weaponized against us.” Fu flings open the doors to the realm of pretend and invites readers to consider ways of exerting agency over what could be wielded against us. Wings might be the tools of flight, but they are also “noticeably stained by the lighter-coloured earth.” People are both amazed and damaged. A woman’s lips can be “crusted violet from the wine.” Leaves can begin “to wilt and droop, shrivelling, to ribbons.” A motel room’s ceiling can be damaged with “a long curl of paint splitting away from its home.” The past can obliterate the present “like a parasite bursting from its host.” But someone can be “appealing to look at, like a glazed cake.” Or they can care for their “appearance tenderly, with small, vain touches, like grace notes on a sheet of music.” Where there are limitations, there are possibilities too. Fu’s characters often stretch to build connections, discover and explore their inner selves and relationships, but more often they survive collisions and severances. The emphasis on plot is immediately engaging, but the collection’s success relies on an underpinning of characterization, always consistent and occasionally thrumming with a curious intensity; these are not only entertaining fictions, but demanding and rewarding. Mark this title on your TBR and put an asterisk beside it: it’s a smart collection and it smarts a little too. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|