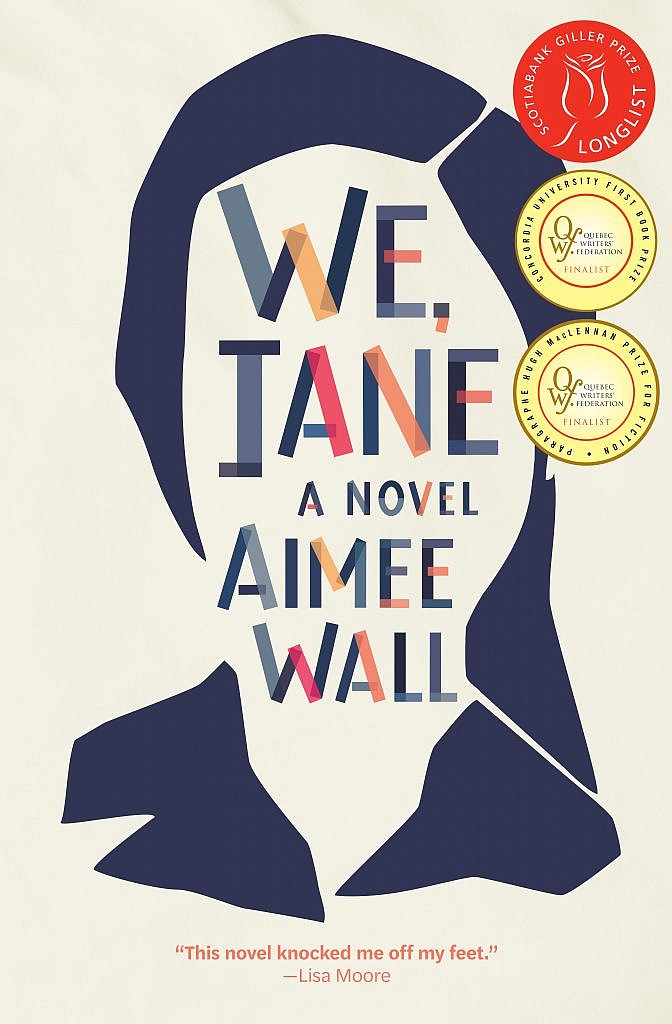

We, Jane

|

|

Invoking the 1960s Chicago Jane collective in both name and spirit, We, Jane by Aimee Wall re-imagines the underground abortion movement in present-day Newfoundland. The novel follows Marthe as, single and aimless in Montreal, she finds herself in a perpetual state of aspiration. Reflecting on her own abortion years earlier, Marthe attends a midwifery meeting in the hopes of finding a grassroots abortion rights group to ally herself with, but instead meets a woman she calls Jane who, like Marthe, is originally from Newfoundland. As Jane—later Ruth—tells Marthe about the Newfoundland Janes, Marthe, desperate for a cause, turns her aspirations homeward.

From early in the novel, Marthe’s “sharp longing” for nothing and everything—her desire simply “to be obliged”—is shown in the way she recasts interactions to make them seem more favourable. A text from her recurring booty call is “reconfigured” to “sound better.” Ruth tells Marthe her real name from the outset, but Marthe wilfully forgets it, “recolouring all her memories” until Ruth becomes Jane. When Marthe realizes, some months later, that Ruth is in fact Ruth, Marthe avoids facing up to the consequences of this aspirational reconfiguring by committing the same act again: she “tried to consider her situation, she tried to adjust the story.” Desire is a beloved theme in novels about gendered experiences, and We, Jane is no exception. Again and again, Marthe prioritizes desire over the world’s insistence on specifics and facts. Her revisions become the book’s narrative realities, supported by the stream-of-consciousness format. We as readers don’t learn Ruth’s name until Trish, an interloper, finally calls her by it, breaking Marthe’s curated illusion. This narrative unreliability is among the novel’s biggest strengths. From the very first pages, Marthe frames herself as a writer trying to pen “the Great Canadian Abortion Novel.” She describes herself as an artist facing “so much raw material,” and notes that Ruth, too, “operated under the assumption that Marthe was an artist still percolating a first great work.” At other times, Marthe conceives of herself as a performer. The problem with her past relationships with men, she reflects, is that they “didn’t leave much room for her own little performance, her work, her own thing.” Despite this observation, her grasp on what “her work, her own thing” might be remains tenuous. Her vague, repeated catchphrases—“her own thing,“ “to be obliged”—are the only glimpses we see into the true locus of Marthe’s desire. Comparatively, Marthe ascribes to Ruth the quality of already having lived. Ruth “made herself some good stories, and now she was inviting Marthe along to create a new one.” It’s this that attracts Marthe to Ruth—who manages, in Marthe’s esteem, even to cast Newfoundland in a more perfect light than Marthe remembers it. If Marthe conceives of herself as a novelist in the making, she sees Ruth as the self-possessed artist. The central question of the novel is what Marthe desires—not only in the present moment, but also for her future. In Ruth, Marthe sees not only the woman she wishes she was but hopes someday to become. At the book’s outset, Marthe has few strong friendships, no partner, and no professional ambitions. It’s as though she fails to see a future for herself—until she sees it in Ruth. It is only after Ruth’s sheen wears thin and Marthe is immersed in the environment of the Jane collective that her sense of her own future becomes more developed. As her desires sharpen, Marthe’s aimless ambition—the book’s narrative engine—finally begins to settle. Throughout the book, Marthe draws on experiences of her own embodiment to ground her in her aimlessness. Her attendance at the midwifery group where she initially meets Ruth stems out of the experience of her own abortion—a subject on which Marthe is uncharacteristically passionate. Much of Marthe’s longing stems from having had an abortion—not because she regrets it, but in fact because she doesn’t. She makes clear she isn’t sure she ever wants a child, or even a family in the traditional sense—though she does note that, in the absence of both, she also lacks a focus for her longing. Marthe finally recounts to Ruth that she used to imagine for herself a cozy rural life in Labrador with a family, where she might have grown potatoes. Marthe never wavers that her abortion was the right choice, but the fact of the abortion replaces both the family she once longed for and the desire for a family she no longer feels. What is left is the abortion itself, focusing that longing: to spread this gift, of an honest and self-determined connection to her body, to those for whom access is limited. Marthe’s return to Newfoundland allows her a different type of embodiment, which also settles her aimlessness. Restless with the Janes in their nameless village, Marthe finally returns to St. John’s after years away. There she meets with old friends, following familiar patterns: she hears the same gossip, goes to the same bars, hooks up with the guy she always hooks up with. The next morning, when Marthe concludes that this life could never be what it was, her nostalgia is sated. As with the rural family she no longer wants, her desire does not reside here anymore. In immersing herself bodily in the city’s new patterns, she is finally able to put paid to the past and begin considering her future. In a remarkable choice by Wall, only then does the work of Jane really begin. Only in the book’s final pages—when Marthe has finally turned her focus to her own honest, self-determined future—are we are finally exposed to practicalities, to what the Jane collective physically does, to the political repercussions of being underground abortion providers. Much is made throughout the book about who in the Newfoundland Jane collective is and is not a “doer”; Marthe becomes a “doer” at last when the aimless act of aspiration no longer stands in her way. In the book’s final lines, Marthe is able to embody the previously unattainable notion of Jane: “a locus of control in a world that was hurtling…. a great, shifting, multitudenous thing.” Leighton Lowry is an academic editor and genre fiction writer based in Montreal. They completed a Masters in Canadian History in 2017, have previously published on The Toast, and currently work as one half of Copper Spines, a speculative fiction mixed media duo.

|