Interview with Angie QuickInterview conducted by Kevin Heslop

|

|

This conversation took place on January 17th in Angie’s studio, on the second floor of The ARTS Project in London, Ontario.

Well, maybe we could start by talking about the current exhibition, then we can weave poetry-talk in a little bit. So: the impetus of your current exhibition, how you’ve felt about its reception or its participation.

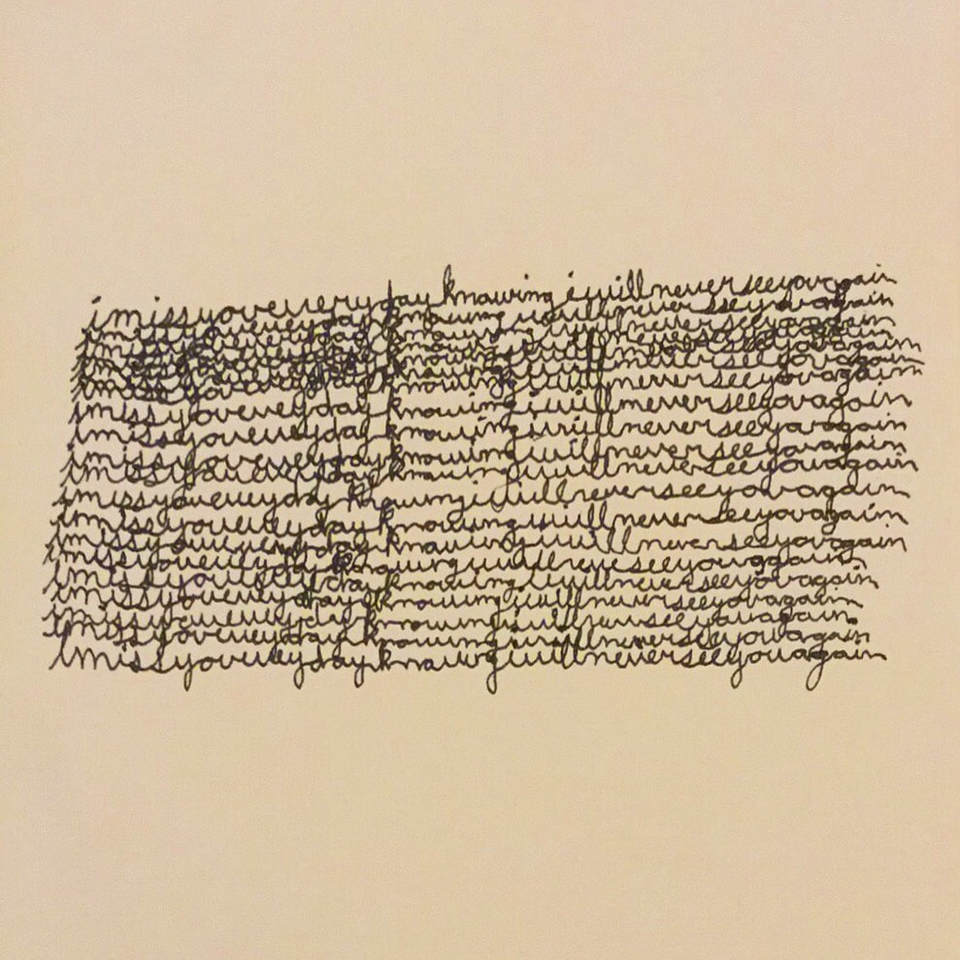

OK. So, the show downstairs is called all my usernames and you, and it’s a collaboration between me and Rob Nelson. And I’ve known Rob for ten years. So–– And you both got gigs here? Yeah. So, we’re both studio-mates. I met him when I first got a studio here, when I was twenty. Wait, that’s not ten years; that’s eight years. You’ve been here for eight years? No, I was here for about two years, and then I left for a while, and then I came back, and I’ve been here now for about two-and-a-half years. So what happened was––we’re kind of shifting right now within The Arts Project, and so there’s maybe more programming and curatorial opportunities happening. So,––there was an opening within the schedule and Sandra [DeSalvo, Executive Director of The ARTS Project] asked me if I wanted to have a show, and I said, Yeah, I like showing my work, but I thought it would be great to pair myself with Rob, and then kind of see where it would go from there, and push each other. Um, I think there’s a lot of things that we have in common in what we do, but it’s not obvious. And since we talk almost every day about what we do, I wanted to see what would happen when we put it into a show. So, when you say that you’re similar but in ways that are not obvious––do you mean that the way the art manifests for both of you doesn’t necessarily indicate similarities but that you’re coming from a similar place? Yeah, that’s what I would say. Because him being a photographer, and then myself being a painter, it’s a very different method. And even as we collaborated it was almost kind of horrifying for me the differences in how something comes about. I mean, for me, I have to order a bunch of canvases, and have a bunch of sketches, ideas, and then I make the work. And obviously there’s a dialogue as you’re making the work where it shifts and it becomes something else, or, just, it moves. Whereas with photography, especially the kind of photography that Rob does, it’s very––there’s a moment that you’re entrapping with another person. For me, it’s like, I’m alone in the studio all the time. And then that moment is accumulated in a series of photos, and then you edit that; and then it’s like, How do you show it? Right. Do you print it? What do you print it on? So, how did those two approaches synthesize in the current exhibition? So, in the exhibition there are pieces that are just mine and there are pieces that are Rob’s. And so, we didn’t really say to each other, This is the kind of work you’re going to make; it was like, I hadn’t been painting––there was some time when I hadn’t made a body of work––so when I moved in here in November, I just started pumping out a body of work. And he––I invited him in to see what I was working on. And he himself started shooting the new work. I didn’t know the new work that he was shooting, but he was seeing what I was doing. And then the collaborative pieces were where he gave me stuff, he gave me old Polaroids of his, and then he gave me photo prints, and then I could do what I wanted with them. So, what did you do with one or two prints, for example. So, with the Polaroids, I had started doing these writing-drawings, which were kind of compulsive, where I would write this line in cursive with no spacing, and then I’d write it again and again and again, so they’d start layering, and it kind of looks like knitting. Beautiful. They’re beautiful. From the series Exorcisms and Compulsions.

And, so, I had some pieces that were just that, and then I took the Polaroids and paired that with it. And I think it’s kind of––it’s interesting because I don’t know anything about the Polaroids; they’re just kind of a found object almost to me. And I know that they’re coming from him, but he didn’t give me any information about them, so I kind of just interpreted them the way I wanted. And some of the prints didn’t make it in, but with one of them I almost erased everything in it with paint until I got the one part that I thought was the best part of the photograph. I think when I first showed it to him he was horrified, but then liked it.

Right. Because it’s like you’re defacing someone else’s art. Right. It’s like, This is the good bit, we’ll keep that. *laughs* Right. And then there was the collaborative video he filmed: I invited a bunch of people who are mutual friends of ours, and then proceeded to kiss them one after the other. So, what was the impetus of that? So, what happened was I was painting and I knew the show was coming up so there was this idea of certain projects we could do, and I was thinking, What if I hired an actor who had to kiss me for half-an-hour straight? And so I ran down the hall and told Rob this, and then he said, Well, what if we do this? Cool. And I said, Oh, well I still want to do the other one, though. *laughs* So, the only example that’s coming to mind that’s similar to that was at MOMA, and I can’t remember the name of the artist, but it was a performance piece where she sat down and maintained eye-contact with–– Abramović. OK. Um, is there a similar sensation between those two? Well, there’s also the work that she does with her partner––I can’t think of his name right now [Ulay]––where they breathe into each other’s mouths, back and forth. I think all of that stuff is kind of in there, in my head. And so, when you’re looking at a performance piece, that can automatically be there. But I guess what I was looking for was a challenge, which is what performance art tends to do––challenge both the artist and the viewer. Right. Both physically and spiritually or emotionally. Yeah. Well, the idea came about and then, to me, in the thinking of it, was that it’s beautiful––it’s a very beautiful idea. And then experiencing it was so much more beautiful. I’ve never really had––I mean, I guess I’ve had experiences like that, but not in the sense that it’s something so public and shared with somebody where it’s considered art. I think everyone should have that experience. It’s nice to kiss somebody without any romantic weight to it. Undertones. Yeah. It’s amazing. It’s like having a conversation. Because I think that kissing is more intimate than having sex with someone. And so, these people, all just different kinds, I don’t know––it was great. So, I guess one of the things that connects the current exhibition with a previous exhibition––Between Us–– No, that’s happening now. OK. Would you tell me a little bit about that? *slightly fatigued sigh* OK. So, Between Us: we have a little room at the front of The ARTS Project which is called The Lab, and so prior to Between Us was a piece called The Wide Skirt in which we created this giant skirt and then we had Andy [Verboom] perform––he created this gorgeous poem––and so, now, the second installation in that room is a piece called Between Us. So, in both pieces it’s me and Sandra DeSalvo making them. And it’s two chairs and we started––we collected people writing poems or stories––and we started sewing them together, so then every Friday until March 23rd we’re inviting people from 5-6pm to bring stuff and then we sew them into it, so we don’t really know how this thing will become. OK. And then, this other project, Between Us and You. Right. Which will be in the gallery which will be a curated thing which is in dialogue with that piece. Wonderful. Um, so is movement towards performance and collaboration feeling like a natural––do you feel tugged in that direction? Or is it just like, as things are coming up, you’re like, That sounds cool. Let’s do it. Yep. Alright. *laughs* I love working alone. I love being alone. But collaborating with people pushes you. And then when I’m given a new opportunity I’m always open towards that. And as to performance, sometimes it just feels like everything is a performance. OK. Um, in a way is a painting then the product of a performance, in a way––it’s like–– Yes. Yes. I would say so. So, it’s the performance that you’re more interested in rather than the consequences which are of secondary importance? From the series Cooler Than Fantasy

Yeah, I do think it’s very important when the painting is finished, in the sense that you suddenly came to make this kind of harmony and balance, but it’s the manner of getting there which is probably the most interesting part which is what people don’t get to experience. But you try to make sure that that energy remains in the painting; and if it doesn’t, then I would say that the painting is a failure or just doesn’t get finished. There’s a lot of learning as you’re painting, no matter at what point you are at in your career. You’re dancing with it, it’s a mood. As long as you’re surprising yourself when you’re painting, you’re making a good painting, because you’re interacting with the moment.

Um, I wonder if there’s a similarity with acting: you do a bunch of preparation, you learn your lines, and then, William H. Macy has this line that you don’t want to dedicate a single brain cell to remembering the words so that when you’re doing the performance it’s almost entirely intuitive, yet you’re drawing from a wealth of research, in a way. And I wonder if you’d say a word or two about what that research looks like for you, if there’s a similarity between those two media. Yeah, I think that’s a great line, though, too, that idea––the embodying of it. What does research look like for me … On a very basic level it looks like a stack of books on my desk and me looking at a lot of stuff. I guess continually being open? I happen to be very lucky to have a lifestyle where I can continue to pursue in any manner. I wake up every day and get to do whatever I want. And so, in a way, structure is good, but I never know what’s going to turn me on, what’s going to suddenly flip a switch. And so, those opportunities, someone says something that I like––I don’t know; it’s hard to say. And then it looks like reading, really. I like to be well-informed. So, that nicely transitions into discussion of the poetry. And, maybe another means of transition could address––I know that a sketch precedes a painting. I was wondering if there’s a similar sketch that precedes a poem, or what that sketch would look like. Mm. Poetry is like a sketch for painting, for me. Oh. So, it precedes a painting? Sometimes. And sometimes I’ll start a painting, and then a poem will happen, and then the poem will help direct me to where the painting is going. So, to me, when on Instagram I put a poem, I’ll hashtag that a drawing, because I see poetry as a drawing. So–– Can you tell me more about that, what that experience is like? I guess sometimes language or how I orientate words next to each other feels like paint strokes. Drawing’s very freeing, but once you start to put a line, a point to another point, then it creates this solid, a weight, whereas words leave a lot of gaps between them. Sometimes words only mean something because they’re next to each other. And that feels more like a painting to me. Wonderful. OK. So, two past exhibitions, House, Home & Hustler, and The Way We Were ... *laughs* Um––they’re not two exhibitions? They’re series; we’ll say series. That’s fine. Series? OK. Um. I only laugh because I’m laughing at myself because I have this weird mentality around titling things that I don’t necessarily know if it makes any sense to other people. Well, I just went to your website and saw that there were four headers and just presumed that they were exhibitions. But you didn’t say that the best one was Cooler Than Fantasy. I’m getting there. I like that when I Google my name it says, Angie Quick Cooler Than Fantasy. And yeah, I Google my own name. So, one of the things that those two series have in common had something to do with posterity, I thought. There’s this idea from Jorie Graham who said that she wanted her poetry to track the experience of the change of seasons, like the sensation of a snowflake, as perhaps in the foreseeable future the distinction between seasons as a result of climate change won’t exist. And so, especially with The Way We Were, I was wondering if there was a similar sense in which you were addressing posterity with an explanation of where we were, to respond to the as-yet-unspoken question, What the fuck happened? In terms of our relationship as a culture to sexuality and intimacy and how we often see those as distinct categories as opposed to mutually supportive ones. Sexuality, for example, can be isolated, and I know that The Way We Were addressed what could be perceived as pornographic imagery? Yes. I wonder if there was a similar sense of retrospection there. Yeah. I’m going tie that together with the new body of working that I’m doing. So, the thing is, with the pornographic work, I was thinking: where do we see the nude body? And within classical art you see the nude body consistently within religious works and there’s a lot of imbued meaning naturally within those: they’re built within a very structured paradigm. So, then I thought, Where does this nude occur now? The nude occurs now in pornography; that’s where we have the most access to it. And so, I wanted to tie those together and create scenes in which it was as though these classical paintings were in a contemporary setting. From the series The Way We Were

Right. It seems as though classical paintings, as you say, exist within a paradigm, and maybe the paradigm hasn’t really changed that much in the sense that especially nude female forms were on a pedestal and maybe pornography does something similar, or perhaps does the reverse?

Yeah, I can see that too, especially in the female sense. But also, I was thinking––and that’s what’s tying with the new body of work with the show downstairs––of the religious structure, which is very important within the history of a lot of paintings. And so, when I say paradigm I mean the way I live my life, how I believe. And so the paintings downstairs are (I call it) the spit-up of old masters, because it’s drawn from that palette, and then thrown up, but all the meaning is gone. Like, Is that Christ being born? But who the fuck cares ‘cause it just doesn’t have––like why would I paint something like that now? Riiight. And so, I see that the same way. And also what you were saying about the environment: so, a lot of the paintings downstairs have a green background, a very blank, green background, and the idea behind that is––because I was also working on these structures of interiors but then the exteriors of buildings––‘cause I was taking this past/present idea. But then I was thinking, Well, if I really want to go back to the past, well, none of that fucking stuff is there. We just got green fields, or maybe there are trees, but just green fields. And I thought, Well, isn’t that similar to what the future is going to be, too, like, maybe in this post-apocalyptic sense? So this green sense really became this idea of this ouroboros uniting of nothingness. Wonderful. So, I was in New Jersey recently and ran into a guy who taught Joyce and Proust for fifty years and he—so he’s very invested in the modernist moment––and it seems like in a way modernism, similar to the moment we’re in now, is between the old masters and a certain religious inclination and future which may have similarities to that religious inclination in the past––and he basically summarized modernism as the moment at which people, devoid of religion, sought some new religion which was reconcilable with secularity. And so, I wonder what, regarding the spit-up of old masters, was being brought, apart from the religious sensibility, to the work that you’re doing now. I guess I’m trying to capture the feeling, what it feels like to look at the painting without that structure being there. Right. Because you really are only going to be able to analyze those paintings by seeing the structure, whereas I want people to be able to grope at them in a way that’s just this immediacy of feeling through it. Like pure sensation, or something. Yeah. And the thing is that with painting, we are in this strange realm where––in the past, you’d follow a school; there’s not really a school of painting; everyone can do whatever they want. Painters become their own schools, in a way, right? Individuals become their own schools, which is the weirdest thing. It’s a weird thing. There’s a certain secularism in that, I guess, in that everyone has their own religion and they’re their own cult leader or something. Yeah. If I can tie that to internet ideas, that’s what the show titles, like all my usernames and you, ‘cause Rob was digital photography, are doing. As a painter, being a painter is an old––what I like about working in oil paint is it’s old, every day I get to work in this old medium. And so then how does that tie together with this internet age wherein, as you said, everyone’s their own cult leader (which is my Instagram life). OK. I wanted to directly address a couple of these poems. The first one: Summer Vacation in a Camping Ground in Denmark. |