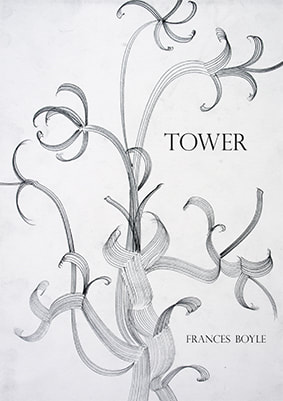

Frances Boyle's TowerReviewed by Amy Mitchell

|

|

This is such a good book. It’s a novella, but it’s so full and rich that it feels like a novel, and a thoughtfully complex one at that. The characters are fully-developed, living people, and the story—an ageless fairytale loosely adapted to show how we hurt and tentatively reconcile with those we love—is both realistic and cautiously hopeful in its depictions of close relationships, whether familial or romantic.

The fairytale in question is “Rapunzel,” with a tongue-in-cheek 1980s twist in which a baby appears in a cabbage patch (Tower is very aware of its 80s and 90s setting, and it gets all the little details correct). Arlys, a stubborn gardener on an island near Saltspring in B.C. who ekes a living out of vegetables and quilts, is positioned to fulfill the part of the witch. When a young, clueless couple move in next to her and plan to grow marijuana—despite not knowing what they are doing—Arlys befriends the woman, Emma, who is pregnant and who discovers that she likes the produce from Arlys’ garden. One night, Arlys finds Bill, Emma’s partner, stealing vegetables from the garden to give to Emma; the couple is having difficulty even feeding themselves. Arlys lets him go. The two disappear a few weeks later when the RCMP raids their land; when Arlys goes outside to investigate the commotion of the raid, she finds their newborn baby girl in her cabbage patch. Eventually, she manages to adopt the girl, who she names Chicory after the peppery, bitter greens that she has taught Emma about: |