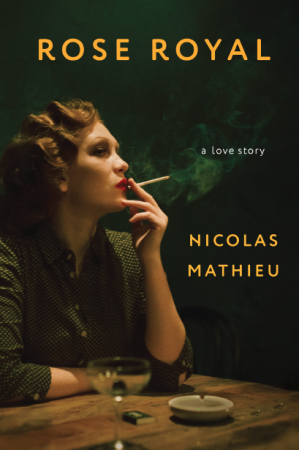

Rose Royal: A Love Story,

Reviewed by Nicole Yurcaba

|

|

In Nicolas Mathieu’s Rose Royal: A Love Story, readers meet Rose, a nearly fifty-year-old woman whose past harbors little more than a divorce and a slew of failed relationships. Rose reckons with her personal worth in the face of a society where youth and beauty determine one’s fate and one’s romances, and another tidbit from Rose’s past keeps reasserting its presence in her life—the .38 caliber handgun she bought after a near-violent argument with her most recent boyfriend. Just as Rose is about to give up on love, a horrific accident brings a glimmer of hope into her life in the form of Luc, a suave, successful man with a nice countryside home and an economic status of which Rose has only dreamed.

Just as readers think they are about to read a modern romance of the fifty-plus variety, they realize that Mathieu’s novella-length masterpiece is something more. What happens in its 84 pages is more than the rise and denouement of a romance; Rose Royal is psychological and sociological, an examination of the way society places professional, economic, and social constraints on women and female-identifying people and forces them to rely on men and patriarchal systems for social and economic mobility. From the novel’s beginning, readers see Rose recognize that she “had reached that difficult age where what remains to you of youthful vigor and electricity seems to be vanishing under the rising tide of day.” Rose determines that she will live the rest of her life alone, working until she can draw her full pension, and she lives comfortably, but not lavishly. In Rose, readers also see a woman shaped to believe that she deserves the violence she receives from men. Rose recollects that “Back then she’d always blamed herself. If she wanted to get it on, she had to pay for the pleasure in the currency of risk.” In middle age, Rose finds the online dating world, and she discovers that the violence now comes with a digital veneer as she endures disappointing dates and men who think they have a right to sex because they paid for dinner. When she meets Luc, she acknowledges that “The people we like always seem familiar, somehow, like an old knickknack on the shelf.” He seems different, and for a while, he is, but slowly Luc’s true nature comes forth, and despite the warning signs and warnings from friends, Rose finds herself trapped. Rose leaves her job, and goes to work for Luc as his secretary, which basically consists of her playing solitaire on her new desktop computer in the office in his lavish house. One of the most jarring moments for readers is when they, like Rose, recognize that if she speaks up, expresses an opinion contrary to Luc’s, or defends herself, Luc punishes Rose with not only physical violence but also emotional abuse. Rose is painfully aware of the role of male violence throughout her life: “Ever since she’d been a little girl she’d had to tiptoe around men and their fits of rage, the ever present possibility of violence, their pig-headed despotism, the fragility of any happy family at the whim of the father’s mood.” When Rose attempts to address what she recognizes as the couple’s drinking problem by hosting an alcohol-free dinner, and afterward, when Luc cannot perform sexually, she says “’It happens… Don’t worry about it.’” Luc responds to Rose’s comment by slapping her so hard he cuts her lip. Luc then leaves, establishing a pattern for the rest of the novella that perpetuates the cycle of violence Rose faces: “There was no sobbing, there were no bruises. It was a violence of allusions, silences, absences. All it took was a single clash and Luc would disappear. She would be left alone for several days, with nobody to share her bed or her meals. Luc had taken her in like a stray dog. And he abandoned her like a dog too.” Luc is the classic abuser: a man who traps and manipulates his victim by off-setting his violence and abuse with affection and understanding. Rose becomes fully aware of the cycle of violence towards the novella’s conclusion:

She recognizes that the violence has determined not only her life’s outcomes, but also her self-worth, because she is embedded in a society that aids and abets male violence, and that “One day nothing would remain in the mirror but the promise of death and her regret that she hadn’t done more with her life.”

Rose Royal is a work of fiction, but it portrays every day events that one could easily read about on the news or on social media. However, unlike social media, Rose Royal is anything but superficial. Part of the dark, psychological twist of Mathieu’s novella is that, much like a spider’s web, readers are caught in Rose’s story and unable to leave it, even when they want to. Rose’s experience becomes their own, and readers leave the novella questioning the social systems in she and they are contained. The novella’s brevity also adds to the shared experience of psychological and emotional torment, since the novella ends as quickly as it begins. The novella’s brevity reinforces not only life’s brevity, but also experiences. Magnetic and powerful, Rose Royal is a work sure to haunt readers long after they finish it, and it will leave readers rethinking the social structures and systems that time and time again elevate and protect the perpetrator. Nicole Yurcaba (Ukrainian: Нікола Юрцаба) is a Ukrainian-American poet and essayist. Her reviews, poems, and essays have appeared in The Atlanta Review, The Lindenwood Review, Whiskey Island, Raven Chronicles, Appalachian Heritage, North of Oxford, and many other online and print journals. Nicole holds an MFA in Writing from Lindenwood University, and she frequently reviews books for Colorado Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Southern Review of Books, and Sage Cigarettes. She teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and works as a career counselor for Blue Ridge Community College.

|