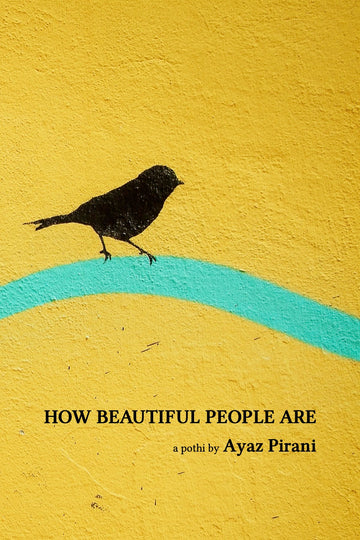

How Beautiful People Are

Reviewed by Padmaja Battani

|

|

Ayaz Pirani’s third poetry collection ‘How beautiful people are’ offers a deep dive into ancestral chronicles, inheritances, passions and pathos. His poems contain a powerful cosmos of cornered lamps, dancing brooms, sand grains, burning coals, men’s suits instilling life into every object and every percept. These poems celebrate people and affirm delight in our humanity, narrating the journeys of beautiful souls.

The collection opens with a series of poems on the topic of ‘historical disadvantages’. Living among unknown (white) people is like living on the edge and on a dog-eared paper. The poet ingeniously relays ‘waves using without hands’ and ‘making dictionary face’ and ‘(not) getting bottled like scents’ portraying images of people whose language is abridged and thin like a Bible’s paper. Pirani’s verse unfolds the spectrum of language where ‘words curve like leaves’ and a drawer of ornithology contains words. Language is seen as a periphery expansion of locations his ancestors travelled and lived. ‘Interrogated nostalgia’ takes the poet to Karachi in search of their ancestral home:

In ‘The doors not talking’, the bookshelf is quiet, the lamp is cornered and ironically the mirror has nothing to offer. With his synthesizing vision, Pirani sees Lake Ontario as not just a blue face speaking plain speech while Lake Victoria appears like a massive childhood grief (from his father’s life).

Pirani’s quiet pride in his ancestors radiates in several poems of the section titled ‘Death to America’. The poem ‘Ngorongoro’ profoundly portrays an intimate image of his grandfather who ‘had the face of a dictionary’ and ‘walked forward’. His grandmother is described as ‘a child of Empire’ in ‘Kilimanjaro’. ‘All the pages of his people’s pothi are in her memory’ thus making her an image of ancestral glory.

In yet other poem for his grandmother, the readers find that her best lines are one syllable and that she has built a home from dung:

These aspects of poet’s ancestors have personally affirmed my pride in celebrating my grandparents’ lives and their upholding of traditional values.

The poet attempts to discover the concealed elements of immigrant inheritances in ‘Where are you from?’. He discloses that the language his villagers speak is not to speak to him. This seems to have a subtle connection to all the people who have lost their languages (to migration) and do not find a road to their villages:

He laments that ancestors are not talking (to him) and that there is no road back once the village is left behind. Yet he hedges his optimism asking what darkness will do when True Guru makes light. Elements of sanguinity can be found in abundance in several poems:

A few poems contain references to the astounding Ngorongoro Crater which is famous for being the largest inactive and intact volcanic caldera in the whole world. A very remarkable notion of emptying pockets into this crater that is known as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa impressed me tremendously.

The poems and the arcs they construct are consistently unique and influential. Pirani shows stunning poetic skill in personifying objects in such a way that the pillows accept the day’s arrangement, stone sets aside feelings and chairs pose.

The use of repetition works powerfully to emphasize opportunity for readers to uphold the extent of spiritual discovery. A grain of sand appears to be a metaphor for something small, yet having been around for millions of years. Purpose and meaning are not destinations, but miles to travel and greatness to find. If one thinks through the parable and takes it further, one will begin to discover something amazing about oneself and the current state of life:

When I have spent some more time and re-read, I encounter certain notions – ‘no pleasure in being myself’ and ‘there is no road to your village’, ‘past is laminated’ and ‘no flag for the undiscovered country’ reemerging in multiple poems. Another sentence ‘True path is to the ancestor’s cave’ echoes the sentiment of people who crossed oceans and lost ancestral homes.

The poet’s choice of quotations from Kabir, Ghalib, Ambai and Philip Lopate are a pure delight. He maintains a tenacious tone and valiantly demonstrates the secluded corners and abandoned experiences of great ginan and granth in many folds while referencing the archaic traditions and lives of ancestors. Padmaja Battani, originally from India, lives in Connecticut/Ottawa. She received an MA in English Literature. Her prose and poetry appeared in Sierra Poetry Festival, Trouvaille Review, New Pages, Coffee People Magazine, League of Canadian Poets, Black Cat Magazine and others. Her latest passion is hiking. She is currently working on a Poetry Collection.

|