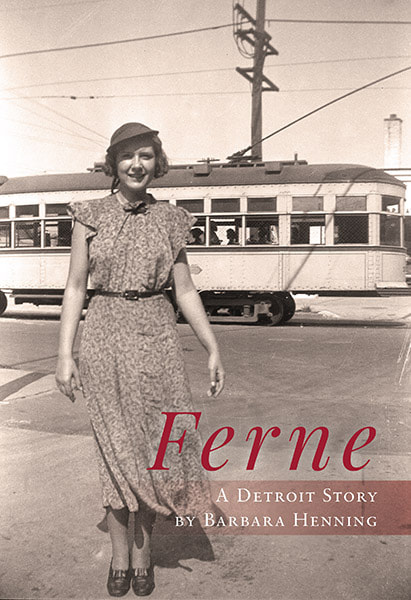

Ferne: a Detroit Story

|

|

In Ferne, A Detroit Story, Barbara Henning celebrates her mother, Ferne Hostetter, within the context of America’s history from the 1920s to the 1960s. This period spans her mother’s life, which ended when she died prematurely due to heart failure. Ferne grew up in Detroit, and Barbara, her eldest child, was born there too in 1948 and was only eleven when her mother died. Ferne was a caring and empathic mother who left four young children and a profound sense of loss in their lives. Her story is humble and ordinary. She was born into a working-class family in which people struggled to make ends meet and worked hard from a young age. The story of the Hostetters interweaves with the great events of the time, such as Prohibition, the Great Depression, World War II, the Detroit Race Riots, McCarthyism and the elections of two important presidents: Roosevelt and Eisenhower.

The story is a fictionalised biography that reconstructs Ferne’s life and reflects the impact of the narratives on the people who surround her. Family relationships are tight, profound and affectionate. They reveal sincere bonds and feelings that are both rewarding and endearing. The impression is given of a caring extended family with strong positive values. Clippings from The Detroit Times offer an additional layer that comments and expands on what is happening in the family, connecting it to the wider society that inevitably influences the lives of ordinary people. Family photos, letters, cartoon strips and advertisements add further layers of meaning and contribute to a multifaceted understanding of Ferne’s story and of the story of the city of Detroit. Ferne is an anti-heroine in her ordinariness, in her simple wish to have a family above all as her mother, Hattie, had, which she attains after two divorces. However, she is also heroic in her determination, creativity and dedication to her four children and to her third husband, Bob. Her positive attitude and her hope for a healthier future for herself and a more equal society are in the spirit of the Hostetters, who live in an all-white environment, but are aware of discrimination and inequalities, especially against Blacks. Though the Hostetters were never well off and had to be frugal in order to pay their mortgages, they always had shelter and most members of the family had a job even during the Depression. This was not the case for most Blacks who lived in crowded and dilapidated segregated areas and were often unemployed. Ferne’s story is both invented and well documented, involving the reader in family life and city life. Henning also questions a woman’s role and its consequences on Ferne’s health, depleting her already challenged energy levels. Big events and government decisions also affect people’s lives deeply and subtly and might cause sudden changes, such as migrations. The stories of ordinary people seem to be the real stories that count; they give joy and sorrow and can sometimes be disappointing but always convey authenticity. Henning is engaged in this labyrinthine quest that builds a narrative of identity. This search for identity is connected to the premature loss of her mother, Ferne, with whom she developed a love story of sorts. Though the scenes of the memoir are invented, they are believable and skillfully reconstructed on the basis of reliable documents. The dialogue Henning writes is mainly developed in the empathic language of love, a deep affection that is revealed in Ferne’s commitment to family and in the ethics and values that she communicates in her simple everyday life. It is a legacy that the author will never forget and one that she creates in the narratives of her mother’s story. Caring is depicted as the element of family life that also is needed in the greater society so that equality and a fairer and more peaceful environment can be attained. After the romance of Ferne’s teenage years and in line with her love of dancing and the stylish outfits she made for herself (she was a skilful seamstress), she focused on her family. After bouts of rheumatic fever, her four pregnancies surely contributed to her heart failure. Her doctor had warned her about the risk of having so many pregnancies, but her role as a mother seemed to matter more to her than her personal health. She felt strong and loved her children, and she was hopeful. However, towards the end of her life she was so weak that she could no longer do housework and needed help. The last years of her life were sad, and although there was the vaguely hopeful prospect of a heart operation, such operations were rarely successful at the time. She died before she had the opportunity to undergo such a procedure. In her last letter to Barbara, she remarks that ‘you may have to take mom’s place sooner than you think’; she ends the letter by saying she sends hugs and kisses to her daughter, final evidence of her caring. The last pages of Ferne’s story, which are very moving, emphasise the loss that will never be replaced; although Ferne’s husband did not abandon the four children, after he remarries, Henning writes about feeling left alone in a world without love in which ‘chaos, despair and discipline’ seemed to rule. The reactions of Ferne’s children were to leave or run away as soon as they were of age, though the ethos of caring and taking responsibility that Ferne conveyed would stay with them forever. Her presence therefore remains strong and everlasting in Barbara Henning’s book; a compelling message about an apparently ordinary woman who was lively and creative and who left a permanent legacy. Henning involves the reader in its enthralling narratives and vivid scenes leaving a sense of belonging and identity. Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She obtained her Degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing with Merit at Lancaster University in October 2012. Her pamphlet Negotiating Caponata was recently published by Dempsey & Windle (2020); she has also self-published a poetry pamphlet, A Winding Road (2011). She has published her work in various anthologies and magazines, and she has recently completed a PhD on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading. In 2016, she and Keith Lander won first prize in the Dryden Translation Competition with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems. She writes in English as a second language.

|