Chapbook ReviewsBy Carl Watts

|

|

To be a poet in North America is to enter the ranks of a perhaps unprecedented glut of literary creators. As Jed Rasula and Marjorie Perloff have pointed out, the numbers are staggering even when one considers merely the number of people teaching in creative writing programs at North American post-secondary institutions. Given the perpetually expanding ranks of aspiring poets this system depends on, as well as the steady retrenchment of traditional publishing, one can expect an accompanying proliferation of alternative publishing methods that perhaps even the shift from print to digital won’t be able to accommodate on its own.

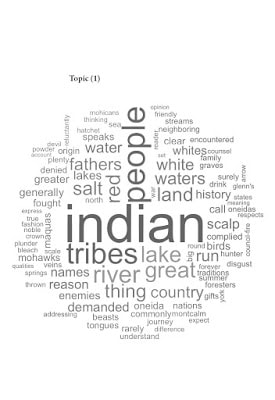

Enter the chapbook, the shabby format that seems likely to become more visible alongside this proliferation. If describing the conventional poetry publishing routine using the allegory of the recording industry, one could regard the chapbook as the EP of the poetry world—a shorter offering that is at once demo and single or, after an artist has released a full-length, something that crops up between albums. Given the format’s lower production costs, print runs, and expectations, however, as well as the ongoing strain on conventional poetry publishers, a more apt comparison would perhaps be the cassette. I don’t mean the format’s role as the portable alternative to mass-market LPs and CDs from the 1970s to ‘90s, but rather its persistence into the 2000s as the medium of choice for some US experimental music communities. As Nick Sylvester wrote on Pitchfork in 2013, the cassette, with its low sound quality and production costs, as well as its existence outside any kind of media hype, is perfectly suited to music that “doesn’t feel desperate or needy or Possibly Important.” Logically, the cassette became the go-to format for extreme subgenres such as noise. And yet, the reason noise artists are drawn to the format—the improvisational nature of the music, extended length of single ideas, and resultant abundance of output—don’t quite apply to today’s poets. Most of the chapbooks I come across are far from the work of outlying radicals or misfits in the poetry landscape. Their authors seem to be playing the game, with the resonance I’ve detected born more of contemporary poetry’s economic constraints. Regardless, and at the risk of being unreasonably optimistic or an apologist for neoliberal austerity, I think the lowered expectations associated with the chapbook are productive in that they let their authors follow through on ideas that could seem either unwieldy if couched in a trade-length collection or, worse, half-baked if extended to that length. The three chapbooks under review here use the format’s advantages in unique ways. Jordan Abel’s Timeless American Classic takes on James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, subjecting it to an eviscerating recombination-and-erasure technique similar to those Abel employed in The Place of Scraps (2013), Un/Inhabited (2014), and Injun (2016). The “Indian” pieces (numbered one through nine and staggered throughout the chapbook) work as an alternate iteration of Injun’s Notes section, in which a single keyword (examples include whitest, frontier, discovery, and warpath) appears on successive lines, aligned in the center of each, with preceding text from the source to the left of the keyword and subsequent text on the right. In Injun, each keyword fits seamlessly into the spacing of the swaths of found text, with the central column visually emphasized using darker text. Timeless American Classic, however, sets the keyword off from surrounding text using a blank column on either side: |