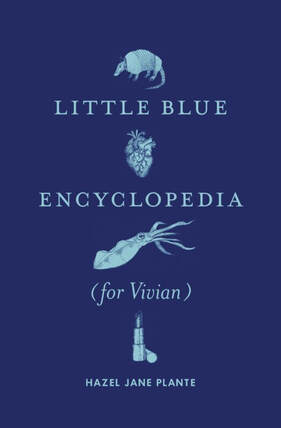

Hazel Jane Plante's Little Blue Encyclopedia (For Vivian)Reviewed by Alanna Why

|

|

“If you spend hundreds of hours with someone, you have a catalogue of tiny memories.” Published at the end of 2019 by Montreal’s Metonymy Press, Little Blue Encyclopedia (For Vivian) is a one-of-a-kind debut novel by Vancouver-based writer Hazel Jane Plante. Written in the form of an encyclopedia about Little Blue, a fictional season-long television series that aired in 2001, the novel is a powerful meta-work about the relationships between fandom, grief and love.

At the core of the novel is the relationship between the narrator Zelda and her recently deceased best friend, Vivian. While the two women are both transgender, they are seemingly opposites in every other way. Zelda is an introverted flannel-shirt-wearing lesbian and self-described “cuddle slut,” while Vivian is a straight S&M-loving pleasure-seeker with a penchant for Britpop and pills. Despite their differences, the pair were united in life for their mutual love for the TV series Little Blue. The novel begins with an introduction by Zelda, explaining that she undertook the project of writing an encyclopedia about Little Blue following Vivian’s death and her own subsequent leave of absence from grad school. Following the introduction, each chapter is organized alphabetically and begins with entries about characters on Little Blue before detailing first-person vignettes about Vivian, her friendship with Zelda and how Zelda tries to cope with the loss of her best friend. It is very unusual to read a work of literary fiction that has as much and as dense world-building as Little Blue Encyclopedia (For Vivian) does – after all, the majority of the novel is a highly-detailed and intricate description of a fictional television program. Little Blue as a television show is described as jarring, dense and overwhelming, or as one character puts it, “totally confusing and totally batshit.” As one fictional review says, Little Blue is “a show that has characters so wacky and unbelievable that they make the Log Lady [on Twin Peaks] look like Carol Brady [on The Brady Bunch].” Plante’s great skill in Little Blue Encyclopedia (For Vivian) is her seamless blend of pop culture fact and fiction. Almost all of its references to musicians and songs in the novel are real – both Vivian and Zelda are music lovers and karaoke fiends. However, almost all of the novel’s references to visual art, books, movies and TV shows are fake, a fact I only noticed on my second reading of the novel. It is a testament to Plante’s writing ability that she is able to create multiple fictional works of art and have them appear to be totally believable – I, for one, was very disappointed to learn that works like An Illustrated History of My Pants by Maritime visual artist Chase Abernathy, and James Bong, a “Seth Rogen-penned stoner spy comedy” starring James Franco, were not, in fact, real. Framing the novel around a television show allows Plante to explore themes of pop culture fandom and obsession, particularly as coping mechanisms for dealing with grief. For Zelda, watching Vivian’s favourite TV show and listening to her favourite music helps her cope with her death. For the characters on Little Blue, art is also the way they survive in the world – the series’ fictional creator Jason Bloch often told actors to “find [their] character’s obsession and zero in on it.” Through the encyclopedia entries, the reader learns that Dalton Fludd, a quiet tugboat driver, spends all his time writing poetry, and Roland Gorse, a farmer, aspires to be a stand-up comedian. The reader also learns that Carter Exby, a very minor character who drives a forklift at the Little Blue Soda Company, makes a newsletter on his own mimeograph machine called Carter Exby Bulletin detailing his love of music, which later inspires a fan to create a Little Blue fanzine with the same title (there is even a footnote to a fictional address where one can send cash to obtain a copy of the zine). Little Blue is also a show with an “abundance of absent characters,” a meta nod to how much the novel is about the absence of its titular character. As Zelda writes, “In nearly every scene of Little Blue, we have one or more characters who are communicating through words or actions that they still miss their loved ones and wish they were here.” Even though Vivian’s absence is felt in the novel, it is very difficult to not fall in love with her character – she is an enthusiastic fashion hound who had a Bride of Frankenstein tattoo, obsessively loved the band Suede and generally seems like an incredibly fun and magnetic person. While Zelda and Vivian were wildly opposite in life, Zelda’s testament to her proves just how important Vivian’s influence was in her life. Vivian was the first trans woman Zelda knew before she came out and acted as what trans actress and activist Laverne Cox describes as a “possibility model”: a blueprint for a way to exist in the world. Discussing the Frank Ocean song “Ivy” after the entry for the Little Blue character Ivy Elder, Zelda writes, |