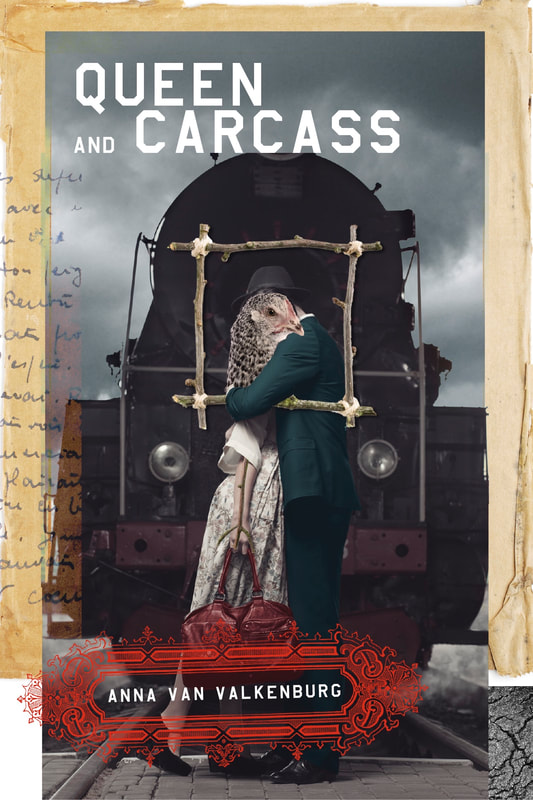

Anna Van Valkenburg's Queen and Carcass

Reviewed by Aaron Schneider

|

|

Queen and Carcass, Anna Van Valkenburg’s debut, is a collection of richly allusive often surreal and haunting poems whose images sink into you, disappearing, only to return days later to reveal another dimension of their strange significance. Steeped in Slavic folklore and dream, and grounded by the careful observation of detail, Van Valkenburg’s writing moves in unpredictable, but deeply satisfying directions, producing juxtapositions that are as unexpected as they are dense and resonant.

Consider, for example, “Melodies,” the first poem in the collection and the one from which it takes its title. At a train station, the speaker hears a train whistle, and, in it, their Aunt Krystyna plucking a chicken. That transition, hearing an image in a sound, establishes the tone of the poem, and, in many ways, of the collection. The opening promises a swerving strangeness, and what follows does not disappoint. The feathers fall from the chicken that is being plucked, and |