Aaron Schneider Interviews Ben Robinson

Aaron Schneider: Where did this book start, and how did it evolve as you worked on it?

Ben Robinson: This book started before I had any idea what it was or that it was. Each time I thought it might be done, a new piece asserted itself, until it was actually done. The very first piece of the book is from January 8th, 2019. I had started the new year by setting a Google Alert on my name, likely in the hopes of catching all those glowing reviews of my work that I kept missing, but instead of praise, 99% of the material that came through was about more famous and successful Ben Robinsons. For some vaguely masochistic reason, I decided to compile the accomplishments of all these other Ben Robinsons in a master document so I could stare at them from time to time. There was something engaging about the material, but I wasn’t quite sure what that was yet.

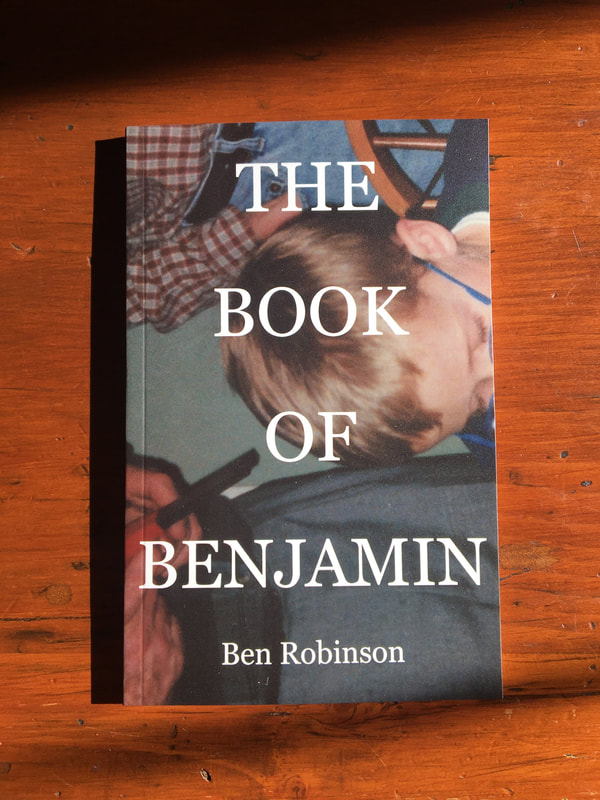

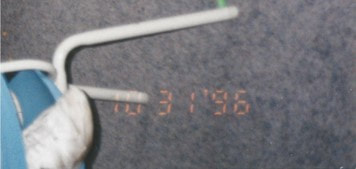

After about a month of this collecting and staring, I started writing what would become the verso pages, short memories about my relationship to my name, mostly from childhood. From there, etymology drove me back in time to the Biblical material, particularly the story of the original Benjamin, which begins with his mother Rachel using her dying breath to name him Ben-Oni or “son of my sorrow.” This story of tragic birth then returned me back to my own family history, but now with the stillbirth of my sister at the fore. I was thinking through this possible connection, the seeming coincidence that this Benjamin and I both had loss written into our names and what this meant for names more generally. Amidst all of this investigating and theorizing, my wife and I learned we were expecting our first child and so the concerns became more practical: how, after all this reading and thinking, would we choose a name for our son? Five years later, he’s now in school and goes exclusively by a diminutive of his own choosing – ever-evolving. AS: This book has you at the centre of it because its starting point is your name, but, at the same time, it doesn’t. It’s about you, about other Bens and Benjamins, and also more broadly about identity. Did you think about the danger of this becoming a narcissistic project when you were working on it, and, if you did, how did you avoid it turning into something like that? How did you start with yourself, and end up with a book that speaks to a set of much broader themes? BR: I’m glad you think it avoids narcissism because that was definitely a concern throughout. The name’s connection to the self seemed to require that the story at least begin with the individual, the personal; my name was naturally the closest material at hand, so that’s where I started. Part of the reason I think it works is the ubiquity of my name. With a less common name this would have been a much different book, and achieving that separation between the individual and the identifier would have been more difficult. So much of my history with my name has been about confusion and conflation. Long before this project, I had already met dozens of other Bens and at least one other Ben Robinson, so I knew that telling the story of my name was inevitably going to expand outward to all of these co-Benjamins. AS: Can you talk about the thinking that went into the format and structure of the book. The left-hand pages are a column of information related to various Benjamin Robinsons, the right-hand pages relate stories related to your name, your family and the origin of the name, and there are a series of images spaced throughout the book. Was the finished format originally how you imagined this book? And how do you see these various elements working together? BR: The format, like everything else about the book, arrived slowly as my understanding of what the book could be developed. I think I understood early on that with such a variety of material, form was going to be important for differentiating my sources. The beginning of the final structure was the realization that I wanted to break up the Google material, that the various elements of the text would need to be in balance. To a certain extent, I’m interested in conceptual literature and found material, but I find my attention often wanders with books where the concept feels self-evident after a couple of pages. The page and page-facing structure of Benjamin is meant to try and sustain engagement and to emphasize the interplay of the personal and the impersonal, to keep them in an ongoing conversation, rather than having them separated off. Here, I was borrowing from books like Anne Carson’s Nox, Jan Zwicky’s Wisdom & Metaphor and Christina & Martha Baillie’s Sister Language which all use the verso/recto format to great effect, to create an energy that compelled me forward while reading them. I also liked the idea that the left and right pages might be advancing opposing arguments simultaneously, that I could say and think more than one thing about names, and that the truth might lie somewhere between the two pages, in the gap. My hope is that the images in the book serve a similar function of disrupting the pattern before it gets too predictable, of managing the pace. When my editor, Jim Johnstone, accepted the book, his one caveat was that he wanted to include a visual element, to utilize the breadth of the form like Jordan Abel’s NISHGA or Matthew James Wiegel’s Whitemud Walking which are filled with photographs and maps and visual poetry and are pushing the limits of the book as a container. The book already included some considerations of family photos, but I didn’t want to include the photos themselves as it felt like doing so would take away from my descriptions of those images. Eventually, I decided to include cropped versions of the date stamps that appeared on these photos so that the reader would have a piece of the image, the texture of that time period, but the scenes would still be left open to my description. My hope is that all of the various forms within Benjamin come together to enhance the whole, to keep the reading experience engaging, and that they form something like a good conversation, each element contributing a new perspective or approach.

AS: I noticed some interesting things about the long litany of information about other Benjamin Robinsons. It felt at once haphazard and structured—that is, there was simultaneously a randomness and a rhythm to it. There are also some recurring themes. For example, there is a surprising amount about Benjamins who play soccer. Can you explain how you constructed this element of the book? And did you create/notice a pattern to the information as you put it together? BR: I tried to avoid altering that material too much. Most of the shaping I did was determining how much Google material to include on each page, how to pace it so it didn’t overwhelm the book. The entries appear in the order they arrived and include only the sentences that contained my name barring a couple of instances where the sentence following seemed too relevant to exclude. Once the book was typeset, I also cut a couple of the longer lists where a Ben Robinson made the school honour roll, or was in the starting lineup of a rugby team, because they were taking over multiple pages of a fairly condensed book – again, pace and balance. Any patterns that occur in the material are not of my design, but maybe a testament to coincidence, that with enough material, there will be, or at least, our minds will search out similarities and continuities. The main pattern that I perceive throughout is that these entries largely document the successes of white men – their promotions, acts of bravery, television appearances, real estate deals and theatrical debuts. There are of course exceptions, including a “Mrs. Benjamin Robinson” – her own name overwritten by her husband’s – and maybe a dozen Black Ben Robinsons including a football chairman. One of the extended sequences that I did leave in the book is about a Black Ben Robinson whose information appeared on a website dedicated to Orange County mugshots. Along with his photo, the website also included dozens of questions with this Benjamin’s name embedded in them – WHO IS BENJAMIN ROBINSON? WAS BENJAMIN ROBINSON ARRESTED? – seemingly designed to improve the page’s search engine rankings. The race of these Benjamins is not always apparent to readers in the same way it was to me as I assembled the material, but it felt important to gesture to some of the more insidious aspects of searchability. Like you say above, in isolation, these entries tell an individual story, but compiled, they raise broader questions – questions about white supremacy, about who reaps the benefits of these digital spaces. AS: Your first book, Without Form with The Blasted Tree & knife fork book, worked through voids, gaps and erasures. The Book of Benjamin is not a maximalist book, but, by contrast, it works through gathering and accumulation. How does this second book fit into your evolving writing practice? Does it reflect any changes in the way you think about or approach poetry? BR: You’re right, there are a number of differences between the two books, not least of which is size: Without Form is a hardcover tome, whereas Benjamin is what Joyce Carol Oates calls a “wan little husk…with space between paragraphs to make them seem longer.” What stands out to me increasingly are the similarities. I wrote Benjamin over the course of about four years (2019-2022) and Without Form emerged in the midst of that writing. At one point, I was even using a piece of Without Form as a working-cover for Benjamin. Both books were born out of experiment, so any differences between them are less about an intentional reorientation and more about gradually determining what approach best suited the given material. They are both engaging with the Bible through revision, recontextualization, and retelling. They are both borrowing from a Jewish Midrashic tradition, via books like Alicia Ostriker’s The Nakedness of the Fathers, which asserts that scripture can and should be engaged creatively. They are both interested in form and structure and paratext and all of those lessons that poets learn about arranging symbols on a page, about the connection between layout and meaning. I guess I think of the relationship between them as less of a progression than two distinct but related approaches that emerged from a similar time in my life and that address shared concerns around Christianity, inheritance and tradition.

AS: I’m interested in craft at a granular level, and I’m particularly interested in the composition of this book. Can you pick a passage, one of your favourites, one that you struggled with, or one has an interesting story behind its production, and explain the decisions that went into crafting it? BR: Many of the craft problems with this book were related to describing absence. I certainly came across this when considering my sister’s stillbirth. Stillbirth itself is a paradox—both alive and not. I struggled with whether to call April 30th her birthday or the day she died, as it’s both. This difficulty came up most pointedly with my family photo albums. I was working on the book during the Covid-19 lockdowns and I knew that I wanted to speak to my parents more about their experience, but I didn’t want to do that over the phone or from the end of their driveway. I also knew that there were likely photos from that time that might be helpful, but given that I wasn’t going into their house, I was left to wonder about what exactly these photos might show. My mom documented my brother’s and my childhoods extensively and there are at least a dozen photo albums from that time. When I did eventually get a hold of the album that included the time of my mom’s pregnancy with my sister, the chronology was visibly off – it’s Christmas, then Halloween, then summer. Also, there is a six-month period, right around the time of my sister’s birth/death where there’s only one photo present. Initially, this absence was really disappointing. After spending so much time imagining what photos might be in there, anticipating how I might write about them, here, instead, was another void, another gap. Eventually, though, I realized the absence and the disorder needed to be the focus, that they documented grief better than a photograph could have. Then the problem became getting that absence down in words so that it could be felt by the reader. First, I had to establish my mom’s photographic meticulousness up to and after that moment, and then make apparent the disorder of the few photos that were present. This section felt like enough of a breakthrough that it’s actually represented twice in the book, once in words and then again in images through the photographic date stamps mentioned above that appear sporadically throughout the text to highlight that sense of rupture in time. AS: Can you tell me what question have you not been asked about this book that you would like to have been asked? And can you answer it? BR: As a library worker, I love a good book recommendation. Aside from the ones that I mentioned above, Rivka Galchen’s Little Labors is an incredible piece of collaged nonfiction that served as a model for Benjamin. It’s another slim volume and was published in an unmistakable bright orange hardcover. Galchen writes about children like no one else. Rachel Zucker’s MOTHERs was also helpful in thinking through writing about family. And, this last one is not a book, but I love the song “What’s In A Name” from the excellent Toronto band Little Kid. Ben Robinson is a poet, musician and librarian. His first book, The Book of Benjamin, an essay on naming, birth, and grief was published by Palimpsest Press in 2023. His poetry collection, As Is, is forthcoming from ARP Books. He has only ever lived in Hamilton, Ontario on the traditional territories of the Erie, Neutral, Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Mississaugas. You can find him online at benrobinson.work.

Aaron Schneider is a queer settler living in London, Ontario. He is the founding Editor at The /tƐmz/ Review, the publisher at the chapbook press 845 Press, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Writing Studies at Western University. His stories have appeared in The Danforth Review, Filling Station, The Ex-Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, Pro-Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, BULL, Long Con, The Malahat Review and The Windsor Review. His stories have been nominated for The Journey Prize and The Pushcart Prize. His novella, Grass-Fed (Quattro Books), was published in Fall 2018. His collection of experimental short fiction, What We Think We Know (Gordon Hill Press), was published in Fall 2021. The Supply Chain (Crowsnest Books) is his first novel.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us