Dimitris Lyacos' Z213: Exit (Volume 1 of Poena Damni)Reviewed by Aaron Schneider

|

|

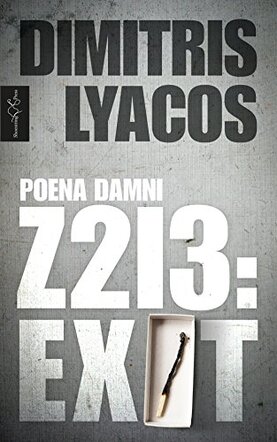

Translated by Shorsha Sullivan and published by Shoestring Press as part of a beautifully-designed box set, Z213: Exit, the first volume in Dimitris Lyacos’ three-volume long poem Poena Damni, is a vertiginous work that is at once archetypal, transcendent, and uniquely suited to this particular moment in time. Poised between novella, poem and journal, Z213: Exit tracks a man’s escape from a guarded building and his flight through a nightmarish, seemingly post-apocalyptic landscape. The man carries with him a Bible between whose passages he records his journey, and the text of the poem is a palimpsest of fragments, “pieces,” quotations and allusions that are simultaneously precise and overdetermined. The effect is to create a reading experience defined by the repeated interpenetration of familiarity and de-familiarization—the convention is estranged from and then returned to itself with all of its strangeness intact—and it makes for a book that is by turns haunting and exhilarating.

At the heart of the book is the man’s journey, and Z213: Exit is a peripatetic work organized around episodes, stops on his journey, hiatuses that are perpetually overshadowed by the threat of pursuit and inevitably broken off by departure. The elements of the plot, such as it is, are disjointed by movement, and fragmentation proliferates across the book, operating at all levels of the text. In an early section of the book, the man reads by the light of a series of matches: |