Ben Berman Ghan's What We See in the SmokeReviewed by Aaron Schneider

|

|

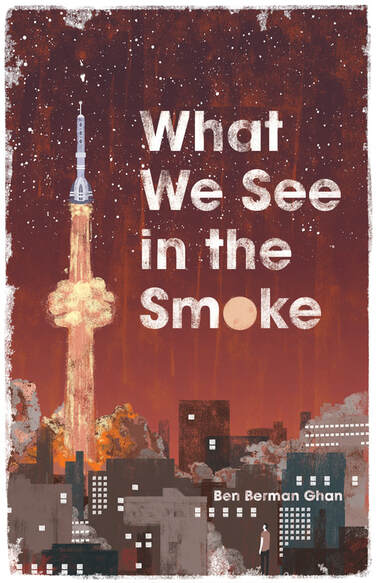

The first thing that you notice about Ben Berman Ghan’s debut, What We See in the Smoke, is the cover designed and illustrated by Raz Latif: a slightly abstracted city at night above which the sky glows a dull orange, darkening into a spackling of stars as it rises away from the ambient glow of the buildings. On the left-hand side of the image, a stylized rocket blasts into space. The rocket and the exhaust from its thrusters form the image of the CN Tower. The rocket mimics the shape of the radio mast that steps down to the small bulb where the exterior of the tower transitions from white cladding to grey concrete. The exhaust takes the form of a widening orange column that bulges midway down into a balloon shaped like the main pod. It is a decidedly clever image that simultaneously plays off the futurism of the tower’s design and articulates the trajectory of the book: What We See in the Smoke is a speculative novel composed of short stories that begins in the Toronto of the present day and blasts off into the distant future, accelerating across a millennium of time and untold distances to touch down in another Toronto on a different planet with a different sky and blue grass, but the same street names and neighbourhoods. 2016 to 3036 is a lot of time and ground for a book to cover, but What We See in the Smoke works, and it works well.

Part of the reason it works is because of the loose way the stories are connected. The book is divided into three sections—“These Memories of Us (2016-2026),” “These Violent Machines (2040-2280),” and “An Uncertain and Distant World (2280-3036)”—that move steadily forward in time. The stories are set in the same world, but don’t share characters, and, even when they refer to each other, function as standalone narratives. We begin in a bookstore in Toronto in 2016 that “sell[s] printed pornography to creatures who haven’t yet discovered the internet” and end in a new Toronto on the planet Janus. Along the way, we meet space travellers, androids of varying levels of complexity and in various configurations, teleporting thieves, cannibals, a clone so thoroughly transformed that it is hardly human, a historian who kills to hide the past from the present, several versions of the apocalypse, and a great deal more. The second section of the book begins with “Yum,” a story in which growing human organs in cows has led to human meat being a commonplace on restaurant menus. Nearly seventy pages and many years later, this narrative thread is picked up in “Closing Time.” An exploration team returns to the irradiated, abandoned ruins of Toronto. The historian on the team discovers the truth of the society that once inhabited the city, including the popularization of cannibalism, and kills her teammates and then herself to prevent humanity from returning to the city and repeating the mistakes of the past. Both “Yum” and “Closing Time” work well on their own, but gain additional layers of significance, not to mention emotional depth, through their juxtaposition. There is a restless inventiveness to the book: each story introduces a new conceit, a new twist or speculative element. This alone is impressive—especially across seventeen stories—but it is more than simply impressive. These the serial inventions replicate the experience of a great deal of time passing. With each story, we leap forward, and, with each leap forward, we have to relearn the rules of the narrative in much the same way that a time traveller would have to relearn the world. This makes for a unique and a uniquely compelling experience. As I have already noted, the novel does not follow a traditional narrative. There are recurrent themes, but no recurrent characters, or, at least, no characters whose arcs see them appearing consistently in the novel. Elements that are central to one story fade into the background or disappear entirely in the next. But the book still holds together. In some ways, it works more like a history, like a history of the future, than a conventional narrative, piling up events in a sequence that is both haphazard and inevitable. History (as least, the imaginative history of the future) doesn’t end, but books do, and the end of What We See in the Smoke could easily have felt arbitrary, even contrived. It doesn’t. Ghan deftly manages to put a satisfying cap on what is, at least structurally, quite an unconventional novel. In the penultimate story, “The War with Space,” a clone on one of the colony ships sent out from earth is born and re-born, evolving with each generation to become better equipped to repair the rent in the ship’s hull that is causing it to slowly disintegrate. When the ship finally reaches its destination, Abe, the clone, looks nothing like a human. He doesn’t even have a mouth, and he has to write in the sand to communicate with the inhabitants of the planet the ship arrives at. In the closing paragraphs of the story, he sees a human child for the first time, and declares his love for this tiny example of the possibility he has been keeping alive by protecting the ship and that is now fundamentally alien to him. In the final story, “And the Stars, Do They Still Shine?,” the unnamed protagonist lives in a new Toronto on the planet Janus and talks to Clarence, a ghost from the old Toronto who may, it is not entirely clear, be a character who appeared in one of the earliest stories in the book. The protagonist is dying of cancer, and he slips into a portion of the city that is slated for demolition. At the end of both the story and the book, he and Clarence kiss as the city burns around them. These twin moments of connection, transformation, disconnection and destruction make for an apt conclusion to a book in which the simple act of moving from one chapter or story to the next is both a loss, a letting go and leaving behind, and a discovery. Thus far, I have foregrounded the speculative elements of the book, but, as you might gather from my description of the closing two stories, Ghan is as good at character as he is at worldbuilding. What We See in the Smoke is filled with a motley collection of people, androids and clones whose emotional lives are as carefully limned as the details of their contexts. Take “Yum,” for example. At the heart of a story about the normalization of cannibalism is a father trying to get a new pair of lungs for his dying daughter. After a violent robbery, during which he secures the organ she needs, he discovers that her artificial lungs have failed, he is too late, and she is dead. The story ends: |