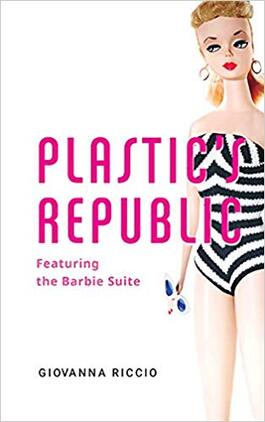

Giovanna Riccio's Plastic's RepublicReviewed by Carla Scarano D'Antonio

|

|

Playing with Barbie dolls together with my sister was one of my favourite pastimes when I was a little girl. We had both the original Mattel doll and a cheaper one bought at the market; its plastic was thinner, almost transparent in the legs, and its head was easily removable and interchangeable. The cheaper one had wigs as well and soft feet you could deform with flat shoes. Our Barbies had only a few dresses as my mother was very strict about dolls and, being a teacher, encouraged drawing and didactic games. We kept their stuff in wooden wine boxes my father provided, and to have more clothing options we used scraps of material we wrapped around their thin bodies and sewed up with big stitches. With the help of my mother, we also crocheted bikinis, tops and skirts. Dressing and undressing Barbie dolls gave us a sensual feeling and creating their stories engaged all our mental and physical energies. My sister and I were not playing with a common doll, a girl-baby doll, but with a young woman, our future selves, and this was a serious matter. Later on we had a dollhouse as well, only two rooms, the living room with orange and gold plastic furniture and a bedroom with a light blue double bed. Ken was a later acquisition, and we were not sure what to do with him.

My daughter had a large range of Barbie dolls but she soon lost interest in them, and when we adopted my second daughter she preferred them naked, taking a deep pleasure in removing their legs and arms. So we threw the whole lot away. Giovanna Riccio traces Barbie dolls’ controversial history from the beginning in vigorous, ironic prose. Barbie was created by Ruth Handler emulating a Bild Lilli doll brought from Switzerland, then modified and adapted by the designer Jack Ryan. The ‘capital doll’ is therefore a copy of a copy from its origin. It is made of plastic, ‘a force that molds or a material that can be molded.’ The manipulation of her person is set from the introductory poem, ‘Homemade Wine,’ in which the female protagonist is involved in booze and sex that anesthetize her aspirations. Riccio cleverly divides the collection into five sections with a foreword and an afterword that guide the reader in this compelling poetic dissertation that analyses woman’s role in modern society, focusing on this role’s construction, sexual exploitation and manipulation by the dominant male power. This also includes environmental concerns, philosophical meditations, and exposure of the incongruities of ancient and modern myths, revealing the sheer logic of consumerism and profit. The poems explore and develop what the author states in the introductory prose piece at the beginning of each section. They operate in conversation with the reader, aiming to inform and reveal what is behind the scenes in a thought-provoking exploration that spurs a rethinking of female roles and of the whole structure of consumerist society. Everything seems aimed to produce profit, and the poet’s role is not to imitate the images offered by such a society but to expose and dismantle their incongruities and artificial quality. The quotations from Plato’s Republic at the beginning of each section underline the dream-like quality of an existence that relies on shadows and images that make us prisoners of a fake world, a simulated reality, a game that has not ‘to be taken seriously.’ Nevertheless, human beings seem to prefer not to look at brutal reality but to ‘flee towards the things [they’re] able to see.’ It seems a contradiction at first, but this reveals a profound need for creating and believing in an imaginary world in order to attain emotional survival. Apparently, ‘humankind cannot bear too much reality,’ as T.S. Eliot says in ‘Burnt Norton,’ but maybe not even ‘too much unreality,’ as Duncan, one of the characters in Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman, claims while misquoting Eliot. We need dreams, storytelling, fiction and simulacra to carry on, but, at the same time, we must be conscious it is made up. The necessity of a more just world emerges in the poems, and this world necessarily involves both more equal gender roles and social justice. Riccio’s lines, broken by frequent punctuation, and her accumulation of rich imagery express this sense of pressure, the anxiety of the imposed feminine role, that is, the Beauty Myth personified by Barbie, to whom no girl or woman can compare: |