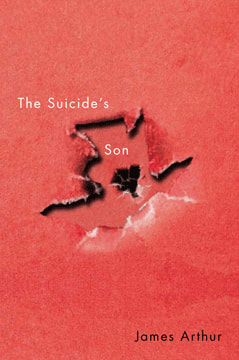

James Arthur's The Suicide's SonReviewed by Carla Scarano D'Antonio

|

Inevitable violence and a nostalgic mood characterise James Arthur’s second collection. Some poems were already published in his pamphlet Hundred Acre Wood (Anstruther Press, 2018), but in the context of this new collection, they appear sharper and more intense. A subtle violence creeps in the lines, freezes moments in tiny details, alienating the subject and leaving the reader suspended in an illusion of observation.

The void of our world is contemplated in a relentless, brave disillusionment. It unmasks our reality, revealing an anguishing emptiness that seems redemption-less. This is a world of artificial images, sad and farfetched, and yet colourful, momentarily appealing and entertaining. These images have the quality of a pastiche, nostalgic and funny; they are performances of imaginary past gesta. Thus, reality is fragmented, shattered, pulverised in an attempt to reach the bottom and maybe start again, possibly with more room, more breathing space and time to rewind: |