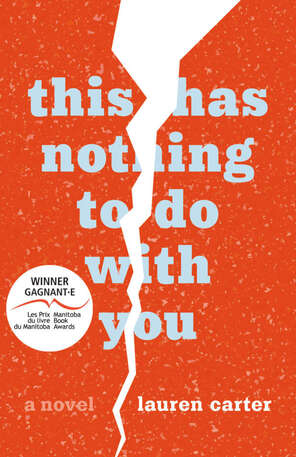

Lauren Carter's This Has Nothing to Do With YouReviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

Whether or not readers enjoy Lauren Carter’s second novel has everything to do with Grommet, the rescue dog: spittle flying, lungs bellowing, barks exploding, toenails clattering and jowls flapping. Simultaneously, readers’ enjoyment has nothing to do with Grommet: cat people, too, will respond. Readers’ success with This Has Nothing to Do With You resides in their capacity to hold conflicting ideas and truths in their heads and hearts.

This novel strikes in “that vulnerable spot where we swallow and breathe.” In such astute half-phrases, Carter crystallizes complex truths. Consider swallowing and breathing—both life-sustaining actions, involuntary yet occupying the same physical space—independent systems working with finesse inside a larger system. Dichotomies abound. Disasters proliferate. Characters wait for rescue even while disbelieving that it will come, and whenever they get close to answers, they discover more questions. Questions that spiral around initiative and apathy, power and responsibility. Enduring questions, like this: “How does one keep watching, with no power, with no control? Is it enough to simply witness?” With Melony, her “history hangs everywhere,” and she is forever “wishing the back wall would open up into another reality.” In time, readers come to understand more about her situation, but she resists this: “It’s easier when people don’t know, when I don’t have to question how they see me.” There is a pattern of concealment, so gaining an understanding requires effort: “We were a family that kept secrets, stayed silent in order to pretend that everything was fine: my mother’s depression, my father’s need to be in charge, how irrational he could be.” The novel’s structure forces a slow-build of comprehension, with different aspects of Melony’s life taking hold in different chapters, as though she is sidling up to reality, to the no-longer-deniable. At times, Melony is overtly processing the trauma that exists in her past. She thinks of herself like a caterpillar strung up in a cocoon, and this sense of time-out-of-joint has endured: “Even back then I knew I’d be snagged in those branches for years.” At times, she is caught up in the day-to-day, remembering that she has a bottle of wine chilling in the freezer and “wondering if it will be ruined.” Melony has her mother’s wide forehead, her brother’s narrow nose, and her father’s auburn hair: all of this is “impossible to escape.” But sometimes the indelible can be altered, and what matters then is how the people around us still overwrite the visible. When she looks at her friend, she sees an historical version of her, even in the present day: “If I squint my eyes, I can push away the slight changes, bring back that brown mole on her left cheekbone that she had removed last year, leaving only the shiny round circle of a scar.” In that sense, these characters inhabit past and present simultaneously. An old Atari system, Star Trek reruns on TV, and Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. album: such details swiftly and securely root readers in 1980s memories. And the music plays such an important role that there’s a soundtrack (and it’s not a gimmick, but a meaningful compilation, with songs woven directly into the story). More than half of the novel is devoted to outward struggle and change; in concert with plottier bits, the substantial dialogue and scenic writing and abundant chapter breaks maintain readers’ interest. The and-also perspective leads to an unpredictable narrative shape and open-ended conclusion, and when Melony sinks into inactivity, readers feel it, too. Even when a keystone is unearthed, there is another layer of realization in the wake of it, making a squiggle rather than an arc. Lauren Carter does not simply create credible characters—she inhabits them. Many writers, for instance, create playlists for their characters. Carter imagines how her characters would alter the lyrics of those songs to reflect their lived experience. Owain, for instance, rewrites John Cougar Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane”: |