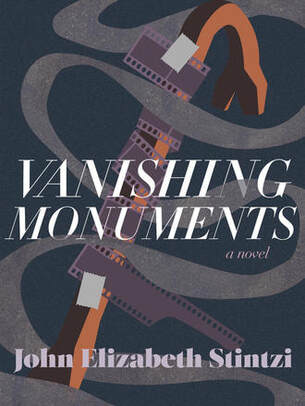

John Elizabeth Stintzi's Vanishing MonumentsReviewed by Alanna Why

|

|

“[E]veryone’s childhood home is haunted. And everyone goes back.” Published in April by Vancouver-based Arsenal Pulp Press, Vanishing Monuments is the debut novel from non-binary Canadian writer and poet John Elizabeth Stintzi. The story is told from the point-of-view of Alani Baum, a non-binary photographer and professor in their late 40s, who returns to their childhood home in Manitoba for the first time in three decades after their Mother’s dementia significantly worsens in a long-term care home.

Vanishing Monuments is a non-linear and deeply interior meditation on memory, gender and trauma. For Alani, returning to their childhood home is equal parts memories and triggers. Throughout the novel, Stintzi guides the reader through each room of the house, dubbed by Alani their “Memory Palace,” and which events each room re-awakens in their mind. The tour starts on the main floor of the house in the hallway, living room and kitchen, before ascending the stairs to the narrator’s old bedroom, as well as their Mother’s room and studio. The novel switches point-of-view throughout the story, going from first- to second-person, with Baum addressing themselves when certain memories are triggered. For instance, when going from the upstairs bathroom to their childhood bedroom, Alani suddenly addresses themselves and their feeling of lacking control by being back at the house for the first time in 30 years: |