Treading Possibilities of the Self in M.W. Jaeggle'sJanus on the PacificBy Adam Mohamed

|

|

An entrance into M.W. Jaeggle’s Janus on the Pacific (published by Baseline Press, 2019) might begin by considering a philosophical request made by the speaker in the Afterword. The speaker understands Janus as “the god of beginnings, endings, transitions, passages, and duality,” and associates him with a series of “thresholds [that] take many appearances—person, place, thing, action.” We too are similarly conceived by the speaker as “shorelines” that divide “ourselves historically” by separating who we were and who we may become. In perhaps the most crucial moment of this collection, the speaker asks us to consider “what … a threshold offer[s] and what … it preclude[s],” which is another way of asking us what parts of ourselves we have “relinquished and subsequently greeted” as a shoreline. To consider this request is to enact a phenomenology where we mediate past and future aspects of ourselves like Janus, who is associated with transitions, and like a coastline or shoreline that pulls and pushes things in place of its presence.

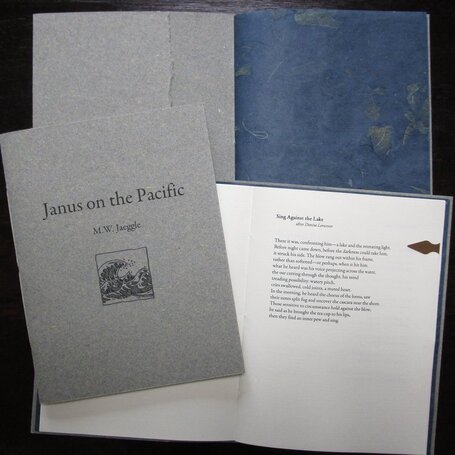

This phenomenology is a model with which to understand ourselves and our experiences, but is also a reading practise used to understand Janus. Janus is conceived in this work as a logocentric symbol, due to his association with metaphors of transitions, like coastlines and shorelines. As such, he represents a form of philosophical conceptualization that structures concepts according to metaphysical dualities. For example, his association with beginnings is always accompanied by endings; where he is seen as an opening is also where he is seen as a closing; if he is a gate, he mediates two oppositional concepts, and he is often visually depicted as having two opposing faces that comprise a duality. The logocentric status of Janus is expected since, according to some Roman myths, Janus is conceived by Caelus (the god of the sky, pointing towards heaven) and Tellus Mater (the god of the earth), which makes Janus the result of a metaphysical duality. In Jaeggle’s collection, this conception of Janus is seen on the cover of the book. We see Pacific waves, and we also see Janus as the square frame that designates where the waves begin and end, as per Janus as a figure for transitions between beginnings and endings. If the Pacific is an un-hierarchical spatial force in which we “stand ankle-deep,” and on which we pull and push aspects of ourselves, then Janus appears to order this space by confining the Pacific within a box, which is separated from the rest of the textured grey cover. The poem titled “What Janus Recites to Himself When He Has Lost His Other Self” comprises a series of acts that Janus performs in his logocentric desire to find an opposing face that he has lost. In the first act, he notes that the world in which he lives presents “no difference between being and appearance.” In search of his other face, he “nourish[es] the seams” that the world makes between being and appearance, and acknowledges that the equivocation between being and appearance is an artificial suture—a “seeming”—that originally separated being from appearance. It’s no surprise that Janus recognizes the possibility of an originary being distinct from appearance, in that the title references Janus’ two-faced hierarchical nature. In the second act, he assumes the presence of God, who exists “before he made heaven and earth,” which is another metaphysical dualism in line with how we are to conceive of Janus. In another act, Janus performs a thought experiment in which he “imagines[s] the absence / of [his] body,” much like the absence of the self of which he is in search. He reasons that he can’t imagine this absence because “it’s no object,” which indicates that Janus cannot understand himself without making himself an object present to himself—a logocentric trope of conceiving the self. There are other poems in this collection which are not so much focused on conceiving Janus, but rather on a more personalized self—a model for how we should enact a phenomenology of mediation that divides our past and future selves. After being struck by a blow in “Sing Against the Lake,” the speaker finds his “inner pew and sing[s]” in an act that appears to be an affirmation of the self. Like Janus and the phenomenology of mediation asked of us, the speaker considers “his voice projecting across the water,” and becoming “sensitive to circumstance,” affirms an “inner pew” within himself. This revelation is similar to the request in the Afterword in which we are asked to take notice of what we—a coastline— “pull in and what [we] … push back into the sea.” In “Kundalini Strand,” the speaker finds a strand of an addressee’s hair curled “like a snake.” The speaker reflects on his childhood, in which he found another strand of hair that he “knew … would belong” to the same person. This equivalency is used as evidence of an inner enlightenment, an “elevation” of the self in keeping with the practise of Kundalini. Even the page on which the poem is printed contains the ends of two threads—like strands of hair—used to stitch a text-block of the book in place: the stitching is a formal assurance of the speaker’s inner elevation. At other times, this elevation is not presented as a transcendental move, but rather as a presupposition of the speaker’s present voice. In “Autumn, According to Childhood,” the speaker objectifies their childhood by addressing it in the third person, much like an earlier poem written in the voice of Janus; by objectifying their childhood, the speaker bypasses an objectification of themself —the speaking voice—and remains an authoritative logocentric voice. But beyond the phenomenology of the self and reading practises used to conceive Janus, there is another, more pragmatic entry into Jaeggle’s work that doesn’t begin with requests. We don’t need to enter at the end of the work by using the Afterword in place of a preface for how we are to read ourselves and Janus. An entrance into the work could be as simple as reading it sequentially and letting each poem culminate in a pragmatic reading. As I’ve found, a pragmatic approach offers quite a different reading of Janus and the self that is more questioning of their logocentric formulations. Consider the concept of an Afterword. An Afterword—something typically seen in scholarly works—is used to designate the ending of a primary body of work. Like the logocentric understanding of Janus, the Afterword demarcates an ending of a work by turning the work into an object against which the Afterword’s difference is asserted. But if we question a reading which makes this work a derivative consequence of the Afterword, then the Afterwork becomes the afterword—not a prescriptive afternote outside the “full” work, but a powerful supplement that asserts itself as part of the work like a muted jewel. In this new afterword, there appears to be a more rhizomatic and un-hierarchical definition of Janus that differs from his logocentric perception. Janus is comprehended as shoreline to mediate the past and future, but he is also described as a threshold. Unlike metaphors of intermediacy, a threshold can be understood as a limit of what is conceivable. Therefore, the threshold does not presuppose two existing objects between which it mediates, but is rather the point at which a system recognizes what cannot be systematized. Understood as a threshold, Janus is not conceived as a truth or a presence but that which escapes those very aspirations. He does not mediate land and sea but is rather critical of his place within the binary altogether. The flyleaf of the chapbook presents Janus as a threshold as opposed to his logocentric understanding. Rather than confining the Pacific into its frame on the cover, Janus—who lies outside of conceptualization—is not present on the flyleaf; instead, we are left with what appears to be leaves floating on the Pacific and Janus somewhere outside of representation. In fact, in many of the poems already discussed, Janus is implied as being a threshold rather than a shoreline or coastline. In “Janus Becoming the Ground,” Janus observes a series of things “collapse” into a uniformity in which he is not distinguished from the objects he describes. The scene around him gradually latches itself onto him until Janus concedes that “I is no history,” and instead identifies himself as a series of moving metaphors, such as time, tree litter, and a resin. An alternate to the self-predicative I, Janus becomes an assemblage with nature in which the subject is not distinguished from the object and in which description that tries to cleave this fusion “ceases.” Aside from this new conception of Janus, a re-reading of this collection also offers a different way to understand the self in a non-mediated way. In “Sing Against the Lake,” there is uncertainty about the speaker’s “inner pew” that follows after being struck by a blow, because it is unclear from where the blow originates: |