D. A. Lockhart's Devil in the WoodsReviewed by Aaron Schneider

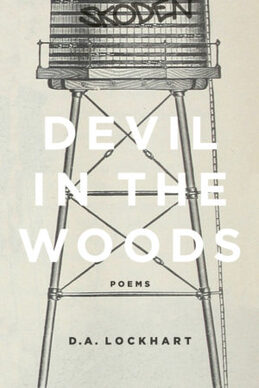

Devil in the Woods, D.A. Lockhart’s fourth collection, is, as the blurb on the back says, a subversive book. The cover is an image of a water tower with the word “Skoden” painted on it in a nod to the same word being painted over the name of the city on the Sudbury water tower in 2018, and the book takes a combative stance towards institutions of power. However, Lockhart’s willingness to interrogate cultural and political authority is not the limit of the book’s subversiveness, nor of the poems it contains. It is by turns aggressively critical, generous, funny, crude, and deeply wise. And its subversivness comes from, or, at least, draws its strength from its tonal range, making it a book whose politics is matched by the depth of its humanity.

The book oscillates back and forth between two kind of poems: prayers, and letters from J.W., an Anishnaabe man from Central Ontario, to a range of Canadian political, cultural and historical figures. Although the breadth that I have described (more on this shortly) plays across both types of poems, there is still a noticeable difference between them. This is a bit of a simplification, but the prayers tend to lean in the direction of joyfulness and hope while the letters tend to be justifiably trenchant. It is a smart and quite powerful juxtaposition. Criticism is, by definition, backwards-looking—it is an accounting and judgement of what has been done. Prayer, on the other hand, always contains an element of invocation, and thus of futurity, of the possibility of what can, and, in time, might be. By pairing these two types of poems, the book weaves together backwards- and forwards-looking gazes, showing us in turn where we have come from and where we can go, moving effortlessly between incision and uplift. At the same time that Devil in the Woods slides back and forth between criticism and prayer, it incorporates an incredible range of tone across the book as a whole, and in individual poems as well, and sometimes across a handful of lines. Consider, for example, “Letter to Kane from the Agnes Jamieson Gallery, Minden, ON, ” a poem addressed to Paul Kane: |

|

Owen tells me even a caricature of a Lakota warrior

is better than thirty pictures of Clydesdales hauling wood. I’ve always maintained neither one’s anything near how a real Anishnaabe guy waits for an Interac payment to go through at Foodland for mastery of form. We’re all images of some true self. Mood is that which we rest upon. |

|

These lines move from the conversational, to the descriptive, and then pass through the colloquial to the philosophical and arrive at the mystical. The distance they travel from “Owen tells me” to “rest upon” is extraordinary for what is only handful of lines. The transition from “how a real Anishnaabe guy waits for an Interac / payment to go through at Foodland” to “for mastery / of form” is particularly effective and also quite hard to pull off without slipping into forced artificiality. That Lockhart does pull it off (and with such consummate ease) speaks to his own mastery of form.

This range is also incorporated into the sentences in the poems. One of the recurrent features and real pleasures of the book is sentences that duck and weave, peripatetic sentences that begin in one place and wander intentionally but not predictably, arriving somewhere that is as satisfying as it is unexpected. Take this sentence from “Letter to Davies from McKecks Tap & Grill in Haliburton, ON,” a poem addressed to Robertson Davies: |

|

Sure, you could say that newspapers are nothing more

than filler between trilogies, but fact of the matter is a legacy is a legacy, regardless of how many inserts from Price Chopper or Canadian Tire you have to throw in it to make it palatable for out-of-towners: discount bread, butter tarts, and off-brand work boots enough to forget the tiredness of small-town cottage life and how little news cycles matter between bird migrations and passing storms. |

|

The sentence begins with a meditation on literary legacy, segues through advertising to the concrete particulars of lower-class, small-town life in Ontario, and ends by opening itself to the rhythms of the natural world. The shifts in subject matter are not predictable, but they work, and they are as effortless as the shifts in tone. Like this one, these sentences have turns, sometimes multiple ones, and they function almost like discrete poems nested inside poems.

Before turning to the critical work the collection does, I want to note two other aspects of it: its attentiveness to class, and its humor. J.W., the writer of the letter poems, is from a decidedly lower-class background, and it shows in his references: packs of Red Hots, “a ’96 GMC / conversion van and just enough gas money,” “free Timbits at community meetings,” and dive bars in Peterborough. It is rare to see this strata of society represented with such familiar authenticity, and absent fetishization. The book is also very funny. We get lines like “Shakespeare spoon-fed to small-town Ontario is inclined / to be cruel like the price of butter at Shoppers,” and |

|

when Charlie

offers you a shotgun spot in the plywood press gondola of the Peterborough Memorial Arena for a midseason donnybrook with Belleville anyone around here would jump faster than a bull moose at a Ford F-150 in rutting season. |

|

This is from a letter poem written to Chantel Hébert, which makes it all that funnier.

For me, and, I think, for most readers, the heart of the collection will be the letter poems that write back to Canadian political, cultural and historical figures. These poems are addressed to people as wide-ranging as Robertson Davies, Margaret Atwood, Al Purdy, Neve Campbell, Duncan Campbell Scott, Pierre Burton, Mary Bibb and Lucien Bouchard. Although they are, broadly speaking, critical, they do mix praise with their criticism. The letter poem to Sarah Polley ends: |

|

believe that there is power in all the little things you do.

Be it burning medicine to greet the new day, standing up to riot police from austerity governments, or playing at the little redheads who try to charm us into believing that violence doesn’t reside at the centre of our myths |

|

J.W.’s takes are balanced, generous (at times, unexpectedly and undeservedly so), and as human as they are fair. But they are also clear-eyed and unsparing, particularly in their assessment of those with power. “Letter to Atwood from the Tribal Voices in Port Perry, ON” takes up her relationship with Joseph Boyden, and offers one of the most succinct and damning indictments of her that I have read. J.W. juxtaposes the Mississauga woods with the Annex and writes:

|

|

I suppose that when one sets out to build a national literature

one does it better in faux gaslight with distant rattles of Bloor. |

|

A handful of lines later, he adds:

|

|

Face it, all

the hastily written sci-fi doesn’t hit the awards circuits as well as some folks think it should, particularly so when one can find a well-tanned white guy [Boyden] to repeat his uncle’s lies and write stories that don’t belong to him for an audience seven time zones wide that couldn’t care less about the many reasons neither redcoat nor bureaucrat could sniff them out. |

|

This kind of direct critical engagement with literary figures, their works and legacies sets this book apart. It is possible to find single poems here and there that engage explicitly and critically with the work of other writers, but a book that makes this one of its central projects is a relative rarity. There is a longstanding debate about the place and function of reviews in Canadian literature. Some argue that they should be positive or descriptive. Others maintain that negative reviews are essential to a healthy national literature. I have never been particularly comfortable with this debate, not because of the various positions people take (most of them have merit of one kind or another), but because of the foundational assumption informing it. The arguments from all sides invariably centre reviews as the primary mechanism by which we (the collective reading/writing community) assess, sort and adjudicate work. Of course, reviews do this. It is, depending on who you ask, either one of or their most important function. However, reviews are not the exclusive or even necessarily the primary venue where this kind of critical judgement can take place. In Canada, there has not, historically, been a robust tradition of books that explicitly write back to other books/writers, that take them up, turn them over and assess them, but there is pattern now emerging in Canadian poetry of books that do this. They are becoming a little less rare. Lockhart’s collection belongs to that pattern, and, with its humanity, range, humor and clarity, it is a powerful reminder that books are often the best place to write about books, and that both writers and readers are better off with a literature that talks back to itself.

Aaron Schneider teaches in the Department of English and Writing Studies at Western University, where he also runs the Creative Writers Speakers Series. His stories have appeared in The Danforth Review, filling station, The Puritan, Hamilton Arts and Letters, untethered, and The Chattahoochee Review. His first book, Grass-Fed, is available from Quattro Books. Visit his website here.

|