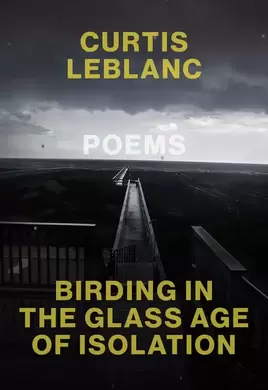

Curtis LeBlanc's Birding in the Glass Age of IsolationReviewed by Aaron Schneider

|

|

The first part of Curtis LeBlanc’s sophomore collection, Birding in the Glass Age of Isolation, begins with an epigraph from CD Wright:

|