John Metcalf's The Worst Truth and Temerity and GallReviewed by Shane Neilson

Enjoying being insulting is a youthful corruption of power. You lose your taste for it when you realize how hard people try, how much they mind, and how long they remember.

—Martin Amis An expert should be able to tell a carpet by one skein of it: a vintage by rinsing a glassful round his mouth. —John Metcalf I.

In the summer months of 2003, I was very unwell. I was just a month removed from my final hospital admission, still not in any kind of recovery, with episodic relapses doomed to continue for another nine months. Of the time, I remember being quite desperate to be better, attending AA meetings even when intoxicated. I wanted to live—but I was quite confused about how to do that. Perhaps the most significant impediment in getting better is that I was yet to be diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, and if you don’t know much about mental illness, you should know this: people with major conditions—things like schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder—can’t get better until they find the right diagnoses and drug(s). Even then, who knows.

I was, in short, a mess. I found myself in Ottawa in June of that year, walking around some mall (I cannot recall the name of it and do not care to remember) that was proximate to the hotel I was staying at with my family. Putting things as I just did isn’t quite right—it was more like, I was staying with them. Janet had a veterinary thing to do in the city, I can’t recall what that was either, but I do know I was responsible for looking after my daughter Zee on the day in question because, back then, I wasn’t working. Not as a physician, anyway. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario wouldn’t have let that happen, nor did I even try to convince them. I was simply too ill, and I knew it. Looking back, it was this knowing that partially explains why I am still alive, writing this line, this essay. Anyway, I’m walking around a mall. Zee’s holding my hand. She’s wearing a pink jacket and carrying a small pink umbrella. We circle and circle and circle the space, repeatedly passing by the LCBO outlet on the ground floor. I’m not even sure why I take her inside because I have no money—I’m broke. I haven’t worked in about a year and I won’t work for another nine months more. But still I go in, holding Zee’s three-year-old hand, to pay my ritual respects to the Captain Morgan shelf (though I’ve never touched the stuff, it was my father’s preferred spirit). I then stand in front of my poison, Smirnoff vodka, on sentry duty. Some time later, I don’t know how long, Zee pulls my hand. “Daddy! Boorrrrrrrinnnnng!” Jostled out of my vigil, we circle the mall some more. II.

In the Winter of 2021, I received a scholarly book for review from Canadian Literature, David Staines’ A History of Canadian Fiction. What didn’t go into that review was a prescient thought I had when I came across the following snippet in Staines’ text, as it happens the only occurrence in which Metcalf is mentioned:

I knew Metcalf wouldn’t, couldn’t take this lying down, because: (1) he’s guilty as charged when it comes to the Waugh imitation; (2) Staines mentions him only because he was eminence grise of the Montreal Story Tellers; and (3) of the two storytellers given the merit badge, Metcalf isn’t one of them.

III.

The day after sentry duty, Zee and I walk to the Elgin Street Diner where we’re to meet John Metcalf. The street is studded with puddles, and Zee loves stomping out pools in boot-sized aliquots. I had submitted an essay to Canadian Notes and Queries about rob mclennan’s work, and Metcalf wanted to meet with me.

“Do you have any more?” he asked in his response. “A perfect target,” he added in person. With each step, I steeled myself to admit to Metcalf at the outset that I had no money, that I couldn’t order anything on the menu, that I was sorry, that Zee and I would just have water. But in the end I was too embarrassed, and simply ordered a small plate of fish and chips that I knew Zee would love. As if everything was normal. As if I had money. As Zee munched, I paid my genuine respects. I mentioned how I had a pristine copy of Kicking Against the Pricks, Metcalf’s first and best mugging of Canadian literature; how I loved the line of fiction he had cultivated at the Porcupine’s Quill, including writers like Heighton, Winter, and Lyon then just beginning their careers; how his encouragement of Philip Marchand to produce Ripostes was a stroke of genius; how his stewardship of Canadian Notes & Queries was providing me with an ongoing education in literary criticism. Metcalf seemed pleased by the praise, but not overly so. He took his compliments and tribute with equanimity and then we discussed some of the writers I had mentioned, the ones he edited. I brought up the fate of his adopted daughter, a woman who – based on his memoir An Aesthetic Underground – had developed the disease of addiction. Metcalf’s face immediately changed, from avuncular to wary. “Yes, well . . .” he said. “Well. There’s no helping any of that.” Talk turned to my own writing by way of what I was reading. “Tell me,” he said. What do you read? You are reading, aren’t you?” We were seated at a table closest to the door. People came and went. “Oh yes,” I said, and listed a swath of Canadian fiction writers. When I eventually got to Atwood, he cut me off. “Oh, not that! Not THAT!” he exclaimed, sniggering like a schoolboy. “NOT HER!” The laughter, though, was calculated, for he stopped immediately, as if he sucked merriment back in. “Shane, you do read internationally, don’t you?” I offered another list: Amis pere and fils; Woolf; Orwell; Rushdie . . . “Oh, well!” he puffed. “That’s better, much better.” But again, this seemed to be just a strategic declaration, since he had no specific comment about any of the offered writers. I merely ticked a box, declaring interest and knowledge. “Now. When it comes to your style. I have a suggestion. Have you ever read . . . Evelyn Waugh?” At that moment, the bill arrived. “I don’t have any money,” I said. “I’m sorry.” Zee looked up at me, afraid. She was the one who had eaten the food. Maybe she thought she was the one who would get in trouble. Metcalf looked at the waiter. After an uncomfortable silence in which I contemplated scooping up Zee and running out the door, forced to leave her coat and umbrella behind, Metcalf said, “I’ll cover it.” I’m not sure if he was disgusted or surprised, but it was one or the other. He hadn’t ordered anything, after all, except for a coffee that he barely touched. Feeling the intense heat of mortification, Zee and I fled as Metcalf opened his wallet, not even stopping to say goodbye or thank you. Why do I tell you this? Well, because I don’t want to pretend that I’m better than anyone else. IV.

Form and content interact. Not only can one not exist without the other, form reifies content and content informs form. They are mutually co-constructed. This fact is widely acknowledged amongst academics, which should be expected—the point is basic. For example, I typed “Sina Queyras” into google. I chose Queyras because I respect her work and because I expected her to be much covered by academics. Picking the first scholarly paper I could find, Jenny Kerber’s “Romantic Ramblings, Revisited: Eco-logics of Mobility in Sina Queyras’s Expressway”, I confirmed my hypothesis:

A hermeneutics of content is amply supplied here, I need not explicate the obvious. Formal analysis is also obvious, with the mention of “mimicry, compression, and punctured syntax.” Note Kerber’s combination of both, however, the facilitation of message by form at the end of the block quotation.

Amongst Canadian literary criticism, however, the debate is far, far, far more naïve, adopting a binaristic frame in which form is pitted against content. Though my belief is as already stated—form and content interacting—if I were to participate in the war as a pressganged recruit, I’d choose the side of form. The reason is simple: I think like a poet. More than all other literary genres, poetry prioritizes form foremost. In this regard I recall Terry Eagleton in Literary Theory: An Introduction--of course you know it! That granddaddy of a book calling for more political readings! Hooboy did he ever get his wish!—who, when writing on the Russian Formalists, opined thus: “To think of literature as the Formalists do is really to think of all literature as poetry.”[i] Eagleton explained Russian Formalism as a school of criticism that tries to wring as much as it can out of the text itself, for that school of criticism conceives of poetry as a “linguistically self-conscious” discipline. In this sense, Russian Formalism is a “how” and not a “what” enterprise, the distinction between which repeatedly comes up in Metcalf’s The Worst Truth when it comes to Staines’ method. A sampling:

Metcalf and pressganged-I, then, concur when it comes to stressing the importance of the ‘how’, or what the Formalists called “literariness.” Yet how different Metcalf and I are in attitude and comportment nowadays, because (1) all Metcalf can bring to the table is a small, measly, and mean critical vision that permits only one narrow version of what “aesthetically pleasing” writing is and might be; and (2) his anti-scholarly stance is, quite frankly, as stupid as he makes those not in his small coterie out to be.

These criteria are, I admit, ideological points—more “what” than “how”—and it is time to tarry exactly here to show that though Metcalf is, in my view, an extremely limited critic, he remains nevertheless valuable in the contemporary moment, both as an example of biliousness not to be emulated, but as a (corrosively) usefully idiotic champion of form. I encourage readers to read Paul Barrett’s takedown (https://canlit.ca/article/make-it-old/) of Metcalf’s recently published third memoir, Temerity and Gall (Biblioasis, 2022) for two reasons. The first is that when I saw that Barrett took this book for review, I laughed out loud because, like Metcalf’s own, Barrett’s opinions largely write themselves. As a literary critic, Barret strongly comes down on the side of content. (See, for example, his servile take in the Literary Review of Canada on Dionne Brand in “The Opposite of Silence”.) I knew that Metcalf’s diversity-wary work would meet no mercy. And style points to Barrett: there are many funny moments in which Metcalf’s text is called a “curmudgeonomicron,” that the author himself is “Palpatinian.” Interestingly, in Barrett’s 1500 word-plus piece there is but a single moment when Barrett identifies the “how” of Metcalf’s memoir:

The second reason I recommend reading Barrett’s piece is because the same problems identified above remain true in The Worst Truth. Though Barrett’s fanatically progressive as a reviewer—think Trade Federation representatives wearing Princess Leia masks—I’m glad for Barrett’s summary because it offers a very useful list that quickly dispatches some shared faults in The Worst Truth. Let me proceed with the identifications in series.

[R]ambling excoriation

One could conceive of the book as an extended excoriation of Staines for his “stupidity”, repeatedly insinuated and actually quoted, as it concerns the crime of content-based summarization of literary reputations. The Worst Truth is 61 pages and it has the lone thesis Barrett noted in Temerity and Gall: “Canadian literature is formally and aesthetically incompetent and is thin gruel.”

Sneering dismissals of Canadian author

If anyone played The Worst Truth as a drinking game in which the reader had to guzzle whenever a “sneering dismissal” floated past their eyeballs, such a reader couldn’t finish the book alive. They’d end up dead (but not more dead than the prose of Metcalf’s fiction.) In the main, Metcalf gets his rocks off insulting early Canadian literature, whacking figures like Mazo de la Roche, Marie Ostenso, and Frederick Philip Grove like Little Rabbit Foo Foo, rarely bothering to quote the authors to substantiate their supposed badness. Early Canlit is stigmatized worse than pedophilia. Later CanLit at least is acquainted with Metcalf’s own interventions as editor, meaning he has a few friends he can praise as exemplary muffins.

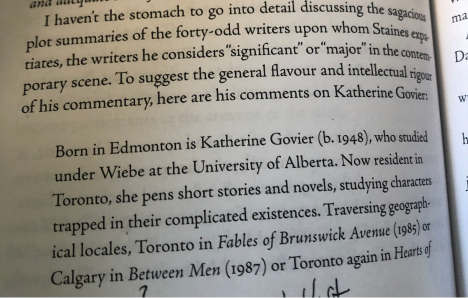

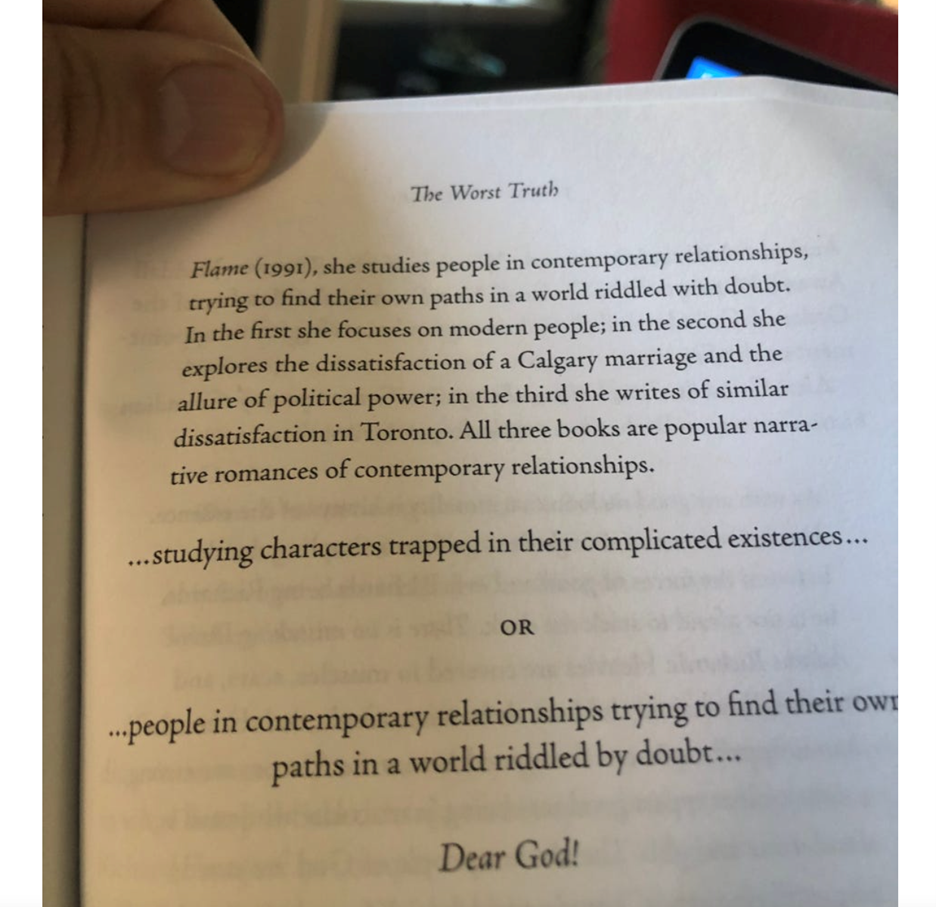

This reads hypocritically because Metcalf is supposedly Mr. How but in The Worst Truth he never musters any proof of taste. Unfortunately for his critical apparatus, his dismissals are akin to a sommelier’s spit-take of wine. Imagine an old, rumpled, bearded, bespectacled man spurting out a stream of red and exclaiming, “What utter shite! An abomination!” and you’ve got the sense of a Metcalf diss track, but only if, in your mind, you also hear the sommelier deliver the harsh verdict in the most ridiculously posh British accent possible. Here’s just one example (from a great many) of Metcalfian spurtings . . . I provide both screenshot and transcription because the typographical niceties of the excerpt should be preserved, to do the prissily punctuational Metcalf justice:

Dear God!

I mean, it’s a real Mon Dieu!!! moment, right? All that showy white space! Of course I get that Staines isn’t delivering scholarly analysis from Mount Olympus here, that his comments are somewhat vague and applicable, perhaps, to any number of possible texts. But I do think that Staines is working within a particular form in which he is obligated to provide quick summary. For any book to be truly appreciated and properly treated at the level of form in a literary history, one needs substantial space to make the case, no? Is Staines supposed to write variations on wine catalogue descriptions in every instance? E.g.,

In this regard, Metcalf reminds me of the contributors to The Literary History of Canada, a 60’s era book[i] stuffed by British expats whose preferred mode of bloviation came in the form of insults hurled at Canadian literary achievement of the 1800s and early 1900s. Metcalf, like the 60s CanLit academics, came down with an extreme case of colonial cringe. (The linkage is natural, of course, for Metcalf is literally cut from the same cloth as those scholars were.) In the face of a larger and more illustrious tradition, anyone who dared write as an attempted part of that tradition as a colonial must be excluded and shamed for not meeting the sponsoring tradition’s aesthetic grade? Such an attitude is callow, and to be frank, Metcalf’s prosecution has been mean-spirited.

It also very much runs against scholarship, for scholarship is documenting what was and is the case; Metcalf doesn’t care that literary history is literary history, he wants to start with modernism only and chuck the rest. Thus his reaction to a scholarly book that constructs a literary history of a nation, which by definition must begin at the beginning, is foolish. It’s as if Metcalf’s mission is to read perversely—as if he, to continue with the earlier analogy, were a restaurant patron who preferred not a menu with dishes listed but instead a detailed description of tastes from which to guess what the meals would be. This might satisfy the true aesthetes amongst diners, but my bet is people just want their Bangers & Mash titled as opposed to rendered into a bumpf of tastebud sensations. (“Ah! The first 2/3 of the tongue will riot at the garlic! And the latter third will salivate as the lumps lift up toward the hard palate . . .” To think! Mein gott!

That some UTTER RUBE might order the garlic/lump dish and expect to get souvlaki! That they WOULD COMPLAIN to the poor waiter that the tastebud sensation record misled them! How stupid they are! They should be banned from the Establishment of Good Taste formerly known as the Elgin Street Diner.

Okay, I’ll knock it off. Poor Dr. Staines, though, for all he can do in the seeming trap set by himself—to write a literary history—is offer one that describe books. Why would he do that? Well, for a simple reason. Content summary is the only stable meaning of books. Scholars looking for some quick content hits—e.g., a grad student who needs to make a list of books with a medical theme—could profit well from A History of Fiction in Canada. After all, the only thing the Literary History of Canada is good for now is its descriptive summaries of old Canadian books. Excepting Frye’s “Conclusion,” the rest can be pretty much ignored, which should be a point of solidarity with Metcalf because theory, although a perpetual concern, is a more periodizable commodity than that which it critiques, literature itself. Books have a shelf life. Theory has a generation. Imagine, though: tasting away the canon, Metcalf-style. The project would be idiosyncratic and hilarious. Can you imagine how silly it would be to aesthetically project a contemporary literary consciousness upon such early works? How oafish it is to project what is essentially a New Critical approach, borne of the High Modernist period, upon the literary romances of the 1800s and early 1900s? But this is Metcalf’s career-long schtick, and it’s heartily kept up in The Worst Truth. After providing a quotation of Margaret Laurence, hardly an ancient of days, he writes:

What gustatory gusto! Even though Metcalf knows that literature has periods and a tradition, he takes no qualms with indicting writing for not embracing what he has decided to be the pinnacle of historical literary achievement (modernism). But using this literary evolution logic, isn’t his preferred kind of writing now invalid, dead, stupid? Though I don’t agree with what I’m about to write, I must argue so to use Metcalf’s logic: Hasn’t postmodernism left literary modernism in the dust?

[G]eneralizations about the foppishness of the Canadian culture industry

Consider this: “Like the yokels at a medicine show the audience was awed by the gravity of mien, the silver splendour of the beard, the Edwardian knickerbockers. . .This had to be art.” Or how about this: “It has been my experience over the last fifty years that many Canadian writers know little or nothing about the Canadian past and have little interest in the doings of their contemporaries.” Check and check.

[P}raise of antiquarian booksellers

William Hoffer is mentioned not once, not twice, but three times. Check check check!

Of all the items identified by Barrett, this one seems to be the weightiest. In The Worst Truth, Metcalf self-quotes at length from his three memoirs as well as his critical text The Canadian Short Story (2018) a staggering seven times! I estimate these quotations as taking up perhaps 20% of the text of the book, but when one combines quotations from Adam Gopnik[i], Alex Good, and Clarke Blaise, among some others, we have a book in which quotation that reaches, perhaps, 40% of its word count. Adding in the long quotes from the ostensible book being responded to, Staines’, the quote percent reaches a staggering (estimated) 65-70%

Barrett’s review of Temerity and Gall soon dispenses with “how” to rush the field of “what”, which is where it stays, and in so doing, demonstrating why figures like Metcalf are required. To the relevant paragraph:

This passage is cunningly descriptive (in the way that Staines is descriptive, but with a negatively critical purpose.) I can feel, reading the paragraph, the same kind of sommelier spitting-out that Metcalf serially practices. Or, perhaps more accurately, I feel as if Barrett is swishing the liquid in his mouth, about to expel it and pronounce it brine.

Jesus Jehosephat!

Barrett’s idea is simple: Taste = an argument from privilege. Barrett seems to be setting up his opponent for an ideological, or, if you will, a “whattian” beatdown. And here it comes:

In its own way, this prose is Metcalfian. Ie., (1) it’s elitist. Consider that the phrase “what most critics understand” appeals to an in-group that thinks according to likemind; (2) it’s limited. It refuses to see Metcalf’s serious (I grant that it is such to him) engagement with the aesthetic as profound as any other theory might be. Furthermore, it makes perhaps the most basic critical point possible, that of the existence of subjectivity; (3) it’s insular. It only uses the sources it prefers—academic ones in this case—to substantiate its arguments; (4) it’s arrogant. It doesn’t self-interrogate, in other words. It takes what it thinks as holy writ, as self-assured as any Metcalf page is.[i] And, perhaps especially, (5) Barrett’s prose presents itself as dogma, as evident truth, making me ask this question: Can taste, when argued at the level of form, not be “reasoning and analysis?” For Metcalf has done some of that kind of work in his many previous books, including in Temerity and Gall, if not in The Worst Truth.

Most interesting to me, though, is how Barrett just confused “what” with "how” at the end of the previous block quote, a key misidentification that proves to me that Metcalf, a fool, is a necessary fool. For here is the rest of Barrett’s passage:

Funny, right? But see how in the cutting humour Barrett just blew past how Metcalf is, in essence, a New Critic of a sort, that his argument is in fact very clear about how he sees—that it, too, is part of ‘theory.’ That Metcalf’s taste is oppressively totalizing I grant, but to not ‘see’ how Barrett’s importation of theory into the discussion to delegitimize Metcalf’s arguments is exactly the same kind of error Metcalf makes when he insults the ‘cult of theory.’

To one way of looking, Barrett’s ‘what’ is actually a ‘how.’ Theory as the thing that shows, reveals, etc. But at the current moment, theory has become something that conceives of taste itself as a bad taste, as something to be spit out in the Metcalfian fashion. At least at the level of non-Metcalfian literary criticism, theory has largely—but not exclusively—abandoned its function as a lens and is more serving like ideological content delivery. In other words, it’s transformed from a how-machine to a what-machine. Misidentifying Metcalf in the way Barrett has is proof of that. When phrased in the most generous way possible, Metcalf is a too-lonely voice arguing for aesthetic appreciation of literature. His ‘what’ is ‘literature’ and his ‘how’ is ‘aesthetic appreciation’ that’s based in form. Metcalf doesn’t use literature as a raw [a + b = oppression] material as scholars do. Literature doesn’t provide him content with which he can make ideological arguments, unless you count “CanLit sucks” as an ideological argument – that taste is only an ideology insofar as it is an obscuring one that works to hide oppressive forces. Or, in other words, to not approach taste as taste as Metcalf considers it. Don’t we need voices like Metcalf, critics insisting on the worth of an aesthetic practice, because on the other side, ‘most critics know’ Barrettian scholars who entrap Metcalf’s ‘how’—aesthetic appreciation—within a ‘what’-container to invalidate it? Barrett says Metcalf’s ‘how’ is actually just the product of a kind of privilege, placing him into a critical context to be sure, but somehow along the way this contextualization is separated from the things Metcalf finds important, like beauty and how such abstract notions are delivered by form. Metcalf hates theory and academics in general; this position is impossible to change because he has no concept of literature beyond his version of literariness. For its part, the academy left New Criticism behind long ago, and has even grown suspect of its exclusionary ideological assumptions. One side points to the other as committing sins of “what.” Each side prioritizes “how” on its own terms. Each side is repellent to me, and I can’t root for either, though if I had to pick one, I’d pick one. Read on. V.

At the beginning of this essay, I contended that I don’t “want to pretend that I’m better than anyone else.” Metcalf’s comically narrow conception of literature, one based on taste alone, is not wrong; I do the same, albeit less. Based on Metcalf’s limited list of greats, I’m certain I love far more kinds of writing than he. Yet, just as Metcalf does, I either like something, or I don’t; the job of literary criticism is to explain why, and this is a far harder task than to critique the means of the seeing, or what Barrett deems using “a sophisticated critical eye” that “strives to be aware of how its own vision of the text shapes interpretation.” The word “sophisticated” rankles me for its arrogance, but this is hardly an alien attitude for Metcalf. Not foreign to Metcalf is an assholic tendency to assert only without explaining why. I wonder about humility, about fallibility, about recognizing that my means of seeing has a default, that of mere partiality and fractional understanding. Declaring humility in oneself is a contradiction, I recognize this; and anyone who writes polemics—Metcalf constituitively, Barrett rarely, and I’ve penned my share too—needs (in some cases) arrogance to instigate change. There is (in some cases) an arrogance in asserting that change need be made. There is also a self-reflexivity – apparently, Barrett’s holy theory grail—involved in considering one’s preferences and habits. As Martin Amis, one of Metcalf’s exemplars, says in Experience, we all have our blind spots. I am not qualified to expound upon mine, these being hidden from me, though perhaps responses to this piece will rush to fill in that gap. Remember, use craft!

VI.

Having consumed newspapers since the time I learned how to read, I’ve on occasion come across the opinion column format in which odds and ends are appended to a longer, more cohesive narrative. In this format, readers are given a quick series of items, each with a brief commentary. There is no expectation that the items be sutured together into a larger argument. Instead, they just are. I think this the ideal format to present to you my marginal notes concerning Temerity & Gall, for my additional reading of Metcalf’s umpteenth writing/editing/bitching memoir would, if I had integrated the material into the foregoing prose, have made my argument ponderous and repetitive. And to be repetitive is to be Metcalfian. But to not write out my supplementary jokes would come at significant temerity to my gall.

On Temerity and Gall

1.

For a writer who gets high on punctuation dope, I note a great many curious punctuation choices in the text. I don’t mean errors, per se; I mean the pinnacle of punctuation, that of style (note the italicization, that’s a deliberate Metcalfian choice of mine!) Consider if you will: “Ray Smith, when I dug him out from the bar, was affecting a sort of US State Trooper or Smokey Bear hat; he was as usual, morose.” Hmmpf! As any good Metcalfian knows, there needs to be a comma before the “as usual”. Not having one there really ruins the performance, don’t you think! Jolly good, oho!

2.

At a distressing frequency, one comes to truly wonder about Metcalf’s reading skills. In the early going of his memoir, for example, he tries to contrast a snippet from Stella Gibbons’ Cold Comfort Farm with a bit of Matt Cohen, shoving paragraphs side by side and demanding a taste test:

The sum of Metcalf’s analysis is a simple Cyril Sneer, as follows: “Not much difference between them except that Stella Gibbons is being intentionally funny. This pseudo-lyrical verbiage readily won the imprimatur of CanLit’s academic finest, and it is they, in large part, who are to blame for the morass that CanLit quickly became.”

Really? Not much different? To my mind, there’s quite a big difference, actually. In the Gibbons, I detect a strong sense of sound, with many internal rhymes chiming through the whole production. Heavy assonance and consonance and all that. One also notes some interior thought breaking through what otherwise seems like omniscient narration. One also notes a sentence fragment as well as long terminal iterative comma splice. Oh, and there’s some repetition in the paragraph too. (Oh no, not repetition!) I suspect these are the qualities Metcalf means when he writes “pseudo-lyrical verbiage” and, granted, I can’t opine that I love the paragraph either. Nevertheless, it’s quite different than Cohen’s where there’s no interior thought, for starters. The Cohen’s all omniscient third person, to the best I can tell. The Cohen is also much more indulgent in pathetic fallacy. SO MUCH MORE WEATHER. Though the Gibbons deals in weather too, but it’s an active and interesting description. The Cohen is pastoral, and in being so channels quintessential CanLit. Sentence structure-wise, we have a similar terminal sentence as the Gibbons, but it’s less forceful. The Cohen includes verbs in its splices whereas the Gibbons was more lyrical, comfortable providing image after image. The Cohen in the main seems more boringly narratively driven whereas the Gibbons—and by no means am I saying I like the Gibbons—and by now I am hoping you are laughing at every single time I italicize something, because basically I am imagining I am electrifying Metcalf on the chair when I do it, bzzarp--is comfortable doing lyrical work. To say, “This is lazily poetic, and so is that” is to summarize a vast amount of literature. One has to do more work! But over and over again in Metcalf, there is just such a pointing. We will come back to pointing. We will, eventually, resuscitate this pointing. Jolly good!

O God! 3.

Anyone familiar with Metcalf knows the favoured writers among his stable, because he’ll tell you. And tell you again. You’re either familiar or you’re his familiar. But in case you needed the list crystallized, here it is, with framing pomposity helpfully left intact:

Okay, I had to cut off the nauseating self-importance at the ellipse. I think of my readers as anti-familiars: no need to tell you and tell you again and again . . . at any rate: look at that list! How WHITE and HETERONORMATIVE it is! And how could it not be? Metcalf loves writers who work within a high modernist tradition, though one must wonder, based on the writers listed, if he also loves certain familiar cultural symbols as well.

Jolly good!

4.

Not only are arguments duplicated between The Worst Truth and Temerity and Gall, whole blocks of prose are too. I mean, when you repeat yourself, it’s best to go all in! But since I’m on the topic of duplication. . . the sheer reprint word count is astounding in T & G. Metcalf’s a serial self-quoter, excavating previous chunks from his memoirs as if this is a normal thing to do. Who else does this? Ha! For someone who hates academics as much as he does, Metcalf might do with some introspection. He seems a lot like his sworn enemies. Taking another page from their book: when he’s not repeating himself, he’s repeating his use of the words of others, such as an epigraph from W.P. Kinsella that’s so giggleicious, he reprises it for extended commentary in the main body of the text. Why didn’t Metcalf really push the duplication aspect even more and copy every fifth page of the book, adding close to another 80 pages to the total? That way he could get it out of his system, clearing the decks for his next memoir to not quote Temerity and Gall. I nominate the following title: Bright Shiny New All-Canadian Metcalf Fuck Atwood Memoir. 5.

The early going of this book is tough trodding. Anyone familiar with Metcalf’s simple arguments against the aesthetic integrity of Canadian literature will see all the golden oldies replayed here again and again. Part of what makes this argument repetition interesting is the lengths he takes to self-quote, as per above. If one decides to read Temerity and Gall perversely as an exercise in appreciating how much a writer can compulsively repeat themselves, then it does get intellectually exciting as the number begins to defy human comprehension. Being of a formal bent, I like to try to identify textual reasons as to why the repetition is so licentious. Part of the repetition compulsion is due—of course!—to incompetent structure. On page 15, Metcalf quotes Clark Blaise at—what else!—considerable length. Blaise’s words are a prompt of sorts to get Metcalf thinking about CanLit’s road to perdition, but the prompt is quickly abandoned—Mein Gott!—only to be returned to—Jolly Good Oho Oho!—on page 92! Over that span, there occurs perhaps the most bilious ramble ever conducted by a literary critic I’ve ever read.[i] You say it can be included in Most Bilious Canadian Rambles? Well, if that’s all I can get . . . jolly jolly good!

6.

Metcalf often mentions the difficulty his career has faced in retaliation for his criticism. Here’s just one instance, and forgive me quoting Metcalf when he’s quoting himself, it’s rather hard to avoid:

In other words, the whole national enterprise is corrupt because he was not included?

I have to hand it to Metcalf. There could be no clearer self-indictment than that which he has brazenly written above. His judgements are motivated by resentments. Forgive me, but whenever I read prose like this, I write Waaaaaaaa in the margins, and I’ve had to write out baby noises many times when reading this book. (I tried to do it in italics, as an extra fuck-you to our Aesthete-in-Chief, but italics by hand are hard.) Metcalf wants to talk tough? Then be tough. He can’t have it all ways. To claim that literature itself is insulted by one’s own lack of inclusion is a level of arrogance that beggars belief. 7.

Another revealing aspect of Temerity and Gall concerns the inclusion of emails by Dan Wells, the book’s publisher-editor. Over ten times in the first 100 pages, but recurring later too, Dan quite wisely advises Metcalf to modernize and complexify his arguments. Wells reads as uncomfortable with how repetitive Metcalf’s “Canlit sucks” argument is, urging Metcalf to acknowledge specific instances in which the argument needs to change. Who knew, but Dan feels that much of what irritates Metcalf is no longer the case, yet Metcalf keeps needing to whack and whomp nevertheless. Wells’s interventions arrive as the proverbial voice of reason, though there is a possible note of self-preservation. Perhaps the other thrust of Wells’ concern about Metcalf scorning the Canada Council so mightily is to preserve a relationship with the mighty grants bureaucracy. Wells wants the culturecrats to reform while protecting Canadian cultural content, whereas Metcalf wants them rubbished outright because they have an inclusive, as opposed to elitist, view of literature. So, on the one hand, we have an editor admonishing their author to argue better, and in every single instance Metcalf responds to the emails with defiant shoulder shrugs. It’s as if Wells said, over and over again, “Don’t walk off that cliff!” and Metcalf gleefully goes ahead and chooses clifficide. On the other hand, I read a publisher repeatedly arguing in support of the system to offset Metcalf’s burn-it-down argument. I can’t help but wonder if the publisher wanted to create distance between Metcalf’s views and those of Biblioasis proper. Don’t bite the hand that feeds and all that. 8.

Metcalf’s favourite poets are all white and old or white and dead: George Johnston, Eric Ormbsy, Robyn Sarah, Bruce Taylor, Richard Outram, and Don Coles. I should say that I love some of these poets (excepting Outram, a tedious rhymester; Sarah, whom I find boring, a poet praised by Starnino & co. solely because then needed to diversify their squad; and Coles, who is, like Sarah, a human snooze button.) There are better poets of this era that could be included: Travis Lane, George Elliott Clarke, M. NourbeSe Philip, I’m just getting started! The point is, Metcalf’s favourites are, as one might expect, all white and, with one exception, all male. The frequency of such demographics do some damage to his arguments about the primacy of the ‘how’ of literature over its ‘what’ (content). 9.

All of Metcalf’s favourite Canadian prose writers are his friends or have published with him. Evidence, and I quote from the book:

Perhaps we can be forgiven for our inability and/or refusal, because we haven’t actually entered into a professional relationship with them like Metcalf has. To repeat my joke, we may be familiar, but we’re not his familiars.

Later in Temerity and Gall, he offers a different syllabus than the above that isn’t quite as transparently connected to himself. He also expands his recommendations to the writing realms of the US and the UK, the point being, of course, that Canadian writing is inferior when compared to that from mommy and our more boisterous brother. It takes an asshole to perform the trick as gratingly as Metcalf does, for the point is obvious, but my real point is to mention that Metcalf’s taste is nowhere on better display in this section in which he valorizes the literary (and white) high modernists of the US and UK. I must also mention again that diversity initiatives by culturecrats come in for major abuse by Metcalf, albeit on ideologically consistent grounds, for Metcalf is an unabashed elitist who thinks that treating writers preferentially based on colour or sexuality does an injury to their talent. He has nothing to say, however, about why it is that such initiatives exist, preferring to live in a bloodless, aesthetic utopia where questions of power are moot. That some would find this their dystopia is never considered. 10.

“CanLit was an assertion of Canadian nationalism, a words-on-paper expression of the spirit of Expo 67. It was always CanLit; it never attained the heights of being literature in Canada.” There is a huge irony permeating Metcalf’s relationship with academics. Though “CanLit sucks” is the short form of his argument, a more specific and subsidiary Metcalf argument is that Canadian literary nationalism was bogus, being the product of the state, an artificial boostering of questionable quality according to suspect motives. This subsidiary Metcalf argument also happens to be the mainstream view of literary scholars. Admittedly, the respective views of both camps proceed along different lines. Metcalf’s is an aesthetic judgement whereas the scholarly view is that Canadian literature was always diverse but that colonial forces worked to make it appear white and heteronormative. The means of the bogusness is different, but the mechanism – nationalism – is shared. Who’d have expected academics and Metcalf to have common cause? Strange times. 11.

Staying on theme carried over from my coverage of The Worst Truth, Metcalf doesn’t really know what scholarship is, he doesn’t know why it’s done. Evidence:

Damn if ‘informed’ isn’t italicized twice! Only an insufferable prig would do that. An insufferable prig!

Jolly good oho!

And consider this take, also on Atwood:

The gist of Metcalf’s argument here and in many other places in the book is that literary history is not authentic. He thinks that writers of the past are not continuous with the present and form no tradition to draw upon. In other words: a literary history in Canada is a contradiction in terms. He can be forgiven for this view for, in a sense, the tradition he inherited from mommy is truly vast. (Metcalf loves his mommy. He loves Mommy so much we should put an italicized very in there somewhere.) He can also be faulted for his love in a more modern sense, for Metcalf’s is the ultimate colonialist viewpoint. But more importantly, he doesn’t seem to understand the point of literary history itself when conducted upon what he deems as terrible writers. I don’t argue that early CanLit writings are aesthetically pleasing, I merely point out that scholarship can be done to assemble writers and writing and arrange them/it in a way that comprises argument. And, it must be said, argument far more thorough and convincing than Metcalf’s fish-in-barrelisms or his mocking ejaculations.

O God!

12.

There’s a cool Billy Joel “We Didn’t Start the Fire” moment in the book. Here it is:

Still, though, I much prefer the hummable:

13.

Metcalf is a “pointer.” His methodology is to not have one. He says, “This is my taste” and c’est tout. I am not making criticism here, since the same practice is my passion too, though I also write out formal analysis to substantiate my taste, all the while recognizing that taste is really all I can assert when it comes down to it, that any truth I might express about a piece of writing is irrelevant to the feeling it asserts in me as a reader. In other words, its beauty, its truth, is all; and the best I can do is point at it and say, “This is it, this is the real thing.” To point is to levy one’s taste and such pointing is an essential service. All the books we treasure and value as a culture have been served by this process in a collective fashion. But. There is a caveat with Metcalf. He often nullifies his taste by merely pointing and not following up on that pointing with any explanation. His is an imperious taste, and I’m far too rebellious to take anything on faith from a writer like him for reasons that should be apparent by now. For example, on pages 44 and 45 he provides block quotes from P.G. Wodehouse, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Rhys, and Samuel Beckett as if his job is done merely quoting them. His argument is, “Hey, dummies, this is GOOD WRITING AND FUCK YOU.” He analyses not a whit of the serial transcriptions. This is abdication. Until. At about page 120, Temerity and Gall pivots and becomes something I’d encourage everyone to pick up and read. For the next hundred pages or so, Metcalf—prodded by a specific resentment (of course) with Andre Alexis who first accused Metcalf of ‘pointing’—provides snippets of his favourite prose and closely analyzes these in terms of their point of view and language choice, offering perceptive readings worth the price of purchase alone. I’d like to provide evidence here, but the excerpts Metcalf works from are quite long and his exegesis of them are more than a couple of pages each. Perhaps I am guilty of ‘pointing’ myself, but if I am, it is because I point to a sustained performance rather than an instance, and I suspect Metcalf might take satisfaction in that description. Take this for what you will, I am by no means an easy judge. Metcalf finally shows the procedure of his taste superbly. Not only does Metcalf pick over his snippets with great detail, he also brings to bear biographical elements upon the included pieces, bits of literary history involving their authors, in what soon becomes an extended love letter to literature itself. Metcalf suddenly unveils the previously hidden reasoning behind his pointing and it’s breathtaking to watch how skilled he is breaking things down. Late in the game, perhaps too late, a reader encounters Metcalf as a substantive critic in addition to being a reactionary and rebarbative one. Metcalf shows that taste is important. It is pointing; but that pointing is also a kind of sign language that, admittedly, can’t churn through texts like theory can. But by communicating enthusiasm, pointing is perhaps the most generous thing a critic can do. It says: Read This, Because I Think it is Good. I think qua Barrett that the nature of Metcalf’s judgements can be stress-tested according to theory, but ultimately if I have to participate in this foolish war, if I have to give up my dialectical stance, I’ll always side with the critic who communicates the excitement of good writing Or: audience score over Tomatometer any day of the week. 14.

Like Geoffrey Hill, I believe that truly difficult art is democratic because it presupposes readers to be intelligent and not fools. I believe in part that how the story is told is the art, not what the story is. Yet I also believe that to ignore what the story is, to discount the story’s being, is to encourage certain kinds of social conditions to come about. It is to cavort in a la-la land of literary modernism unconcerned with issues of race, power, and the like, and this is not wise. I render unto Aesthetic Caesar what is his with great joyfulness and gratitude for what I have experienced in a kind of ecstasy; yet I also render unto Political Caesar what is theirs, too, less in joy and moreso in a kind of thanks that I’ve been given a greater awareness of how I am (and others are) in the world. I praise Aesthetic Caesar for his gift of a connection to the sublime and I praise Political Caesar for a connection to finitude and materiality. When Metcalf writes, “If I know anything about literature with absolute certainty it is that language, not ideas, is its centre” I agree with him to a point while also knowing that, having read Temerity and Gall, he has a limited knowledge about literature. He exchanged context for certainty, though he could have had both. It is as if he thinks of literature as a coin with only one side. For Metcalf, there is no moose, only the Queen’s head. In a weird way, Barrett becomes right on his terms. Metcalf is very much operating ideologically if he refuses to grant admission to theory. 15.

Metcalf discusses his love of poetry and how, as a younger man, he’d deliberately try to steal from poets when writing his own prose. He explains how poets offer up the mysteries of the language for prose writers to use for their benefit. His narrations on this point involving Larkin and Auden are worth reading for any poet. I can’t quibble with his personal list of great poems (works by Hopkins, Pound, Owen, Reed, Hayden, Heaney, Thomas, Auden, MacNeice, Larkin, Crowe Ransom, Roethke, Wilbur, Williams, Graves, Muir) except to say it’s what you’d expect, white and male. Quel surprise. VII.

I can’t stop thinking about standing in front of the shelf of 40 ouncers in that Ottawa mall all those years ago. Despair, like all feelings, cannot be simply named by a writer who wishes for a reader to empathically identify. Craft is of course the means to create the possibility for communicating feeling. But is the point of craft merely to accomplish the technical task, or is writing supposed to display complicated engagements that assist us in negotiating our own lifeworlds? Are we not to learn from our texts, to develop new ways of seeing qua Barrett? Or are we to only marvel at the means of aesthetic conveying, qua Metcalf? Once again, I’ve set up a binary that Canadian literary criticism seems to adopt with Metcalf at the (deliberate?) centre of the conversation.

Let me flip the terms of argument, then. Say—I write a book that documents non-neurotypicality and madness. Say, a book outside the demarcated boundaries of Metcalf’s literary modernism. Say, I’m one of the writers Metcalf has attacked over the years for their non-conformism to his idealized and authoritarian vision of literature. Then you would have to say, and engage your imagination here, that I might as well have picked up a bottle in that store all those years ago, metaphorically speaking. Metcalf will never understand this, but the marginalized identities he doesn’t prefer—remember, his list ‘o faves is superwhite—are vulnerable in real ways he can’t perceive. He is a living hangover of a generation that excluded certain kinds of writers from participation. His legacy as editor at PQL and Biblioasis is the publication of white writers; his self-valorized tastebuds are so white they taste whiteness at an especially low concentration, akin to the superior hearing of dogs. I can well understand how writers who have been sneered at by Metcalf might feel by my imaginatively putting myself in their shoes, yet it is this projection-inhabitation which is the point of literature. Perhaps Barret would agree with this sort of Levinasian thinking. Metcalf might meet me halfway by saying, the only way you’re going to feel anything is if the writing damn well gets you there. Finally! At this juncture, we have form somehow interacting with content. [i] Italics preserved, in what I hope is a funny inauguration of italics, though you’ll have to read on to get the joke. It’ll catch up with you!

[ii] Even Metcalf’s schtick about punctuation strikes me as if he missed his calling as a wine-taster. If you haven’t read his essay “Punctuation as Score,” you really should. Consider the following supposedly masterful italicization in The Worst Truth, one of many: “And that is putting the matter very delicately.” Dude just italicized the word “very”? This is the boomer equivalent of Gen Z’s habit of using exclamations for everything!!! Though at least Gen Z is earnest. . . Metcalf, on the other hand, is just drunk from wine. For proof, see pages 15-16 where the word “astonishing” appears four times. I think the aesthete has left the building . . . [iii] Consider this another joke laid in trap. Hold on for the Billy Joel Moment! [iv] Truly amazingly long, how could anyone block quote to the tune of three pages? [v] After all, not many have the “intellectual brilliance, wealth, and privilege” of a university academic. [vi] The kinds of repetition are incredible too. Quite varied repetitions! He’ll self-quote and then repeat the same self-quote later in the book. He’ll drop sections from previous books that are identified but also some that aren’t identified. In one instance I caught him repeating something he published originally in the Globe and Mail during a dust up from 15 years ago. Shane Neilson (mad; autistic) is a poet, physician, and critic from New Brunswick. His poetry has appeared in Poetry Magazine, Literature and Medicine, Prairie Schooner, and Verse Daily. In 2023, he published The Suspect We (Palimpsest Press), a book of poetry concerning disabled lived experience during the pandemic, with fellow disabled poet Roxanna Bennett. Also in 2023, he published Canadian Literature and Medicine: Carelanding with Routledge.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us