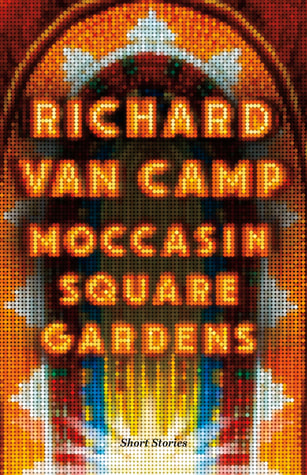

Richard Van Camp's Moccasin Square GardensReviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

My first trip to Moccasin Square Gardens was in “The Last Snow of the Virgin Mary,” a short story in Richard Van Camp’s The Moon of Letting Go. It’s been ten years since that collection of stories was published, and the building still stands. Read this in your most exuberant announcer’s voice: “Welcome to Moccasin Square Gardens. Tonight I, Kevin Garner, am your play-by-play M.C. as Fort Simmer tries to down Yellowknife for the territorial championships.”

As an M.C. in that earlier story, Kevin did a fine job, but since then, the cast of characters has grown, and many individuals are now equipped to guide new visitors through Van Camp’s 2019 story collection, which is titled after the Roaring Rapids Hall in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories. The town, fictionalized as Fort Simmer, has a population of about 2,500 people that speak five languages: Chipweyan, Cree, English, French and Tłı̨chǫ. It’s a “beautiful town – a fierce town when it comes to politics, history, pride, love, exes, peace bonds, child support payments, hand games, Nevadas, bingo and hockey, right?” For readers of Van Camp’s previous books, this will be familiar: straightaway, you will be scanning the crowd for people you might know. Me? I’m always on the lookout for Larry (from The Lesser Blessed) and Torchy (from several stories, beginning with 2002’s collection Angel Wing Splash Pattern). You don’t meet either of these characters in Moccasin Square Gardens, though one of them gets a mention, but you do catch up with Valentina (and trust me: you’d rather not). If you’re starting to feel a little like you’ve just arrived at a house party, when you were expecting an intimate dinner for two, that’s good preparation. There’s a lot of energy in this collection’s ten stories, the fifth collection Van Camp has published. There’s a lot of emotion – laughter and loss – and a lot of interconnectivity. With connections between stories and connections between collections, the sense of community swells. Fortunately, Van Camp is an exceptionally welcoming storyteller. Even when he’s talking about the end of the world, he’s got this way of making you feel like you could move closer to the fire and all will be well. It’s easy to forget that the fire could be apocalyptic: there are two new stories in his Wheetago War cycle designed to disorient and disturb (“Lying in Bed Together” and “Summoners”). Consider his essay contribution to the glossy-paged art book about Ligwilda'xw Kwakwaka'wakw artist Sonny Assu, published by Heritage Books in British Columbia in 2018. Here’s how it begins: |