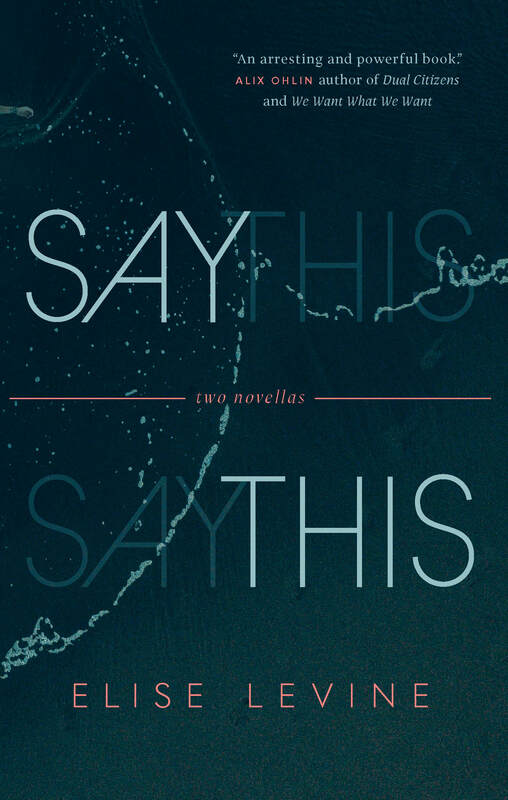

Elise Levine’s Say This

Reviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

“How could I possibly begin to smooth such a mad tangle?” Elise Levine poses this question in her debut novel, Requests & Dedications (2003); her sixth book, Say This, contains two novellas with multiple narrators, all trying to smooth the mad tangle in the wake of a murder.

Levine’s experience with short fiction—two collections, Driving Men Mad (1986) and This Wicked Tongue (2019)—has equipped her to deftly establish mood, inhabit diverse characters, and use structural and thematic details to strengthen the foundation of her narratives. Both “Eva Hurries Home” and “Son One” display her broad skillset, deliberate and bold. Her prose can appear almost skeletal, but she also uses repetition judiciously; she both itemizes and summarizes; and she employs obfuscation and suggestion, but also precision and clarity. In the first of the two novellas, “Eva Hurries Home”, Eva asks herself: “What was she even, back then? Sixteen, fifteen. Thirteen—could she have been that young?” But just a few chapters prior, her memories seemed to extend even farther into the past: “Which makes her fourteen. Or twelve. Or eleven, same summer as the first time.” Part of Eva remains suspended in the past although the novella is rooted in the present: “A new iteration of unfolding. Or more accurately, an in-folding. In this version, nothing would need to matter very much. Not a thing, Pleasure, pain—you name it. But why bother?” Readers realize that Eva does not want to remember some things: “She is all about home to work to home.” Some memories she folds into one another, obscuring details, helping her forget: “She knows what her cousin did, eleven years ago, two years before she found out about it.” She ruminates on her state-of-mind, on the frustrations inherent in binary systems, and emotions that threaten to overwhelm; but she also ruminates on her to-do lists, the state of the Amazon rainforest, and the sound of a subway gate closing. In “Waving” a short piece on writing published in Event shortly after her 1995 debut story collection was published (and collected in Event 50: Collected Notes on Writing) Levine writes about how “odd things stick, stubborn burrs thick with story.” She talks about attending a writing workshop, and then she shares items on a to-do list, the kind of musings one finds on a pocketed scrap of paper. As though, both in and out of fiction, characters and writers are folded into the act of creating their own lives, navigating the space between a shopping list and a meaningful existence. The murder quietly saturates the narratives rather than being obliquely presented. “In its wake, a shiver of hucksters on the scent of a salacious story, chum for vicarious, titillating blood sport. How could she be sure she wouldn’t be contributing?” It’s the kind of pivotal event that a character in Requests & Dedications described like this: “Part of the past that makes us who we are.” Levine’s is the kind of narrative that queries the idea of creating a narrative, even while presenting a satisfying narrative that requires no querying. When readers meet Leonore-May in “Son One” they quickly recognise she is connected somehow, similarly inhabiting a hinged existence: “At that point, May 6, 2005, everything was aftermath.” Each segment of that narrative is titled with one from a set of new characters’ names, all connected to the first novella; it’s like something Eva describes as “the strangeness of walking streets at once familiar and unrecognizable—as if a second map has been overlaid atop a first, off by a slim, uncanny margin.” At the end, the traversed territory is more recognizable, both space and time are difficult to navigate temporarily. One of the characters in “Son One” inwardly asks “is that this or another now” directly confronting the multiple nows (and the implied thens). On one hand, Levine pushes the limits of her narrative and allows questions to proliferate while her characters struggle to root themselves; on the other, her deliberate construction and restraint provide readers with the confidence necessary to explore. At the sentence level, Levine is meticulous: her word selection and structure support the broader narrative and secure readers to the archetypal concepts that buoy Say This. Consider the vocabulary and rhythm of this passage: “She has travelled this far, away and now back, to discover she has been left behind, like a hollow shell washed by shallow waves.” (This watery image recalls Levine’s 2017 novel, Blue Field, which also grapples with the aftermath of a loss—one that haunts an open-water diver.) It all feels inevitable, authorial confidence the necessary counterweight to a work preoccupied by uncertainty. “Remember back then? I’m so glad it’s over, where the heck even was I?” You could shelve Say This with writers like Nancy Lee, Pascale Quiviger, and Michelle Berry, who also examine the blood-and-guts of relationships; with writers like Kim Thúy and Madeleine Thien, who also use language with precision (sometimes sparingly, too) to expose the complex layers beneath simple sorrows; and with writers like J. Jill Robinson and Wendy McGrath, who use perspective and construction to guide readers inside and through vivid and rich lives. In Levine’s hands, readers are left with a sense of being led through the narrative with authority. Not glad the story is over for readers, but glad the characters can find the kind of peace that has eluded them. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|