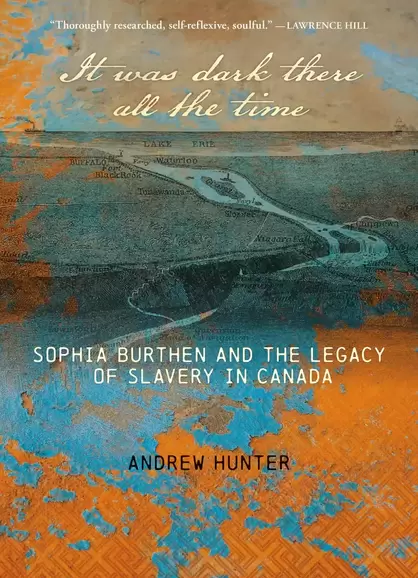

Andrew Hunter's It Was Dark There All the TimeReviewed by Marcie McCauley

Andrew Hunter’s It Was Dark There All the Time invites readers to re-consider historical events through the eyes of one Black woman who lived in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: Sophia Burthen Pooley, who was enslaved by Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk) leader Joseph Brant in present-day New York State and moved with his household to present-day Canada.

Sophia’s original narrative was preserved in 1855’s The Refugee, a collection of The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada by Benjamin Drew. Drew’s subtitle reinforces the view of the north as a refuge for those who escaped enslavement in America, the view of slavery as something that only existed elsewhere. However, Sophia was neither a refugee nor a fugitive in Canada; she was enslaved elsewhere but the terms of her ownership were altered—not abolished—in Ancaster, Ontario. Hunter questions Benjamin Drew’s motivations and privilege, and he questions himself as well. In a chapter titled “On Whiteness”, Hunter wonders whether he, as a white man, has anything valuable to offer to this cultural conversation. Charmaine Nelson (the founding director of the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery at NSCAD in Halifax) addresses his concerns: “The history of slavery is all of our history. This isn’t just Black history; we all have responsibility to do this hard work.” As a schoolgirl, I learned about the Underground Railroad, the network which delivered people enslaved in America to freedom in Canada; I did not learn about slavery in Canada. I absorbed the lesson of Canada’s superiority as described in George Elliot Clarke’s introduction to a reissue of Drew’s book: “We believe our schooling that our settler ancestors, because they did not rebel against the British crown, evolved a superior social order and liberty to that of the violence-prone, if revolutionary, United States.” Viewing Canada as a haven for fugitives from slavery and their descendants depends—as Clarke explains—on “ignorance about slavery in colonial Canada and about the persistence of racism in our ‘post-modern, multicultural’ nation.” Hunter’s work confronts this ignorance and encourages readers to query the historical record and understand its relationship to present-day inequity. Even the subtitle of Hunter’s book insists on contemporary relevance: Sophia Burthen and the Legacy of Slavery in Canada. Hunter’s reflections expose the relationships between injustices. He situates the segregated school system for Black children in post-Confederation Ontario: “The last one to close in Ontario was the S.S. #11 in Harrow, Essex County, in 1965, and the last in Nova Scotia, Lincolnville School, in Guysborough, closed in 1984.” He also contemplates the current overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people in present-day American and Canadian prisons—compared to their underrepresentation in museums, archives, libraries, and schools. And he considers the struggles of present-day migrant agricultural workers: “Their homelands cannot sustain them, but they cannot build a life in Canada either—they remain trapped in an extended Middle Passage.” He broadens the context to include discussions of colonisation and occupation. “The lands where Sophia lived in Upper Canada are traditional Mississauga/Anishinaabe territory,” Hunter observes, and “her time here overlaps with a series of [Indigenous] dispossessions by the Crown, beginning with the Haldimand Tract in 1784.” Reporting on his travels and studies, he reminds readers that the “original Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee are, literally, the people of the earth we are traversing.” As such, Hunter employs some Indigenous nomenclature and concepts, reflecting his commitment to complexity and nuance. Sometimes, his linguistic curiosity is granular and his sensibility more of a poet’s than an historian’s—as evident in his predilection for etymology. Describing his search for a cemetery, for instance, he presents Old English words for ‘ditch’ and ‘to dig’, the etymological roots shared between ‘grave’ and ‘grove’, and a consideration of both groves and graves as sacred places “holding and protecting bodies and souls.” Such ruminations feel like digressions, more commonly associated with a writer’s notebook than a published narrative, but that seems appropriate in a quest for understanding, in the context of an incomplete historical record. Other writers have explored gaps in the historical record too, in non-fiction and fiction. Afua Cooper’s The Hanging of Angélique and Karolyn Smardz Frost’s Steal Away Home challenge cultural conventions about enslaved life in Canada, and Adrienne Shadd’s The Journey from Tollgate to Parkway specifically considers the experiences of Black Canadians in historical Hamilton, where Hunter lives and writes today. Novels like Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes and Gloria Ann Wesley’s Chasing Freedom also present stories that recognise the difficulties enslaved people faced after arriving in Canada. It Was Dark There All the Time exists in the gap between non-fiction and fiction. Like Téju Cole, Claudia Rankine, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Karla Cornejo Villavicencio, Hunter’s work challenges assumptions about non-fiction and fiction. He embeds Sophia’s own words directly into the text, not even separating them from the reader using quotation marks; they appear in a stylized font that definitively marks them as Sophia’s, suggesting that she is not simply the work’s subject but a participant in the work. Consulting a primary source is an historian’s prerogative, but Hunter also writes letters to Sophia, which requires as much imagination as research. Hunter’s persistent open-mindedness, curiosity and determination invite readers to rebuild a relationship with the past, so we can imagine a future where it is not dark all the time. He digs into the work figuratively, just as he literally unearths part of Sophia’s story near the end of the volume. “I wonder,” he writes: “Who cultivated the first flowers here, who planted the apple trees, gnarled but still bearing fruit?” Introducing the concept of wonder reminds us that cultivating new ways of thinking affords the possibility of new ways of living. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us