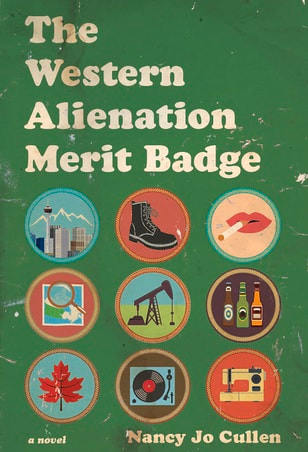

Nancy Jo Cullen's The Western Alienation Merit BadgeReviewed by Marcie McCauley

|

|

Nancy Jo Cullen published three books of poetry and a collection of stories before Wolsak & Wynn published her first novel, The Western Alienation Merit Badge, in spring 2019. The novel’s epigraph is drawn from the 1965 Guide Handbook: “You will often come across things to do and learn that will relate back to things you have already done and learned.” Here, the importance of experience and practice is underscored, the road between past and present illuminated.

It is followed by a one-page scene which presents a young girl pointing a cap gun into the air and firing, then tracing the Guide Handbook’s central image on the cover, before aiming to throw the book into a field and then tucking it into the waistband of her shorts instead: “She was keeping it because this book was for her, right? Even if she was no goddamn Guide Recruit.” The traditional hierarchy in Guiding directs a girl to be a Spark, then a Brownie, then a Girl Guide: but not every community has leaders at all levels of the organization. Never had I heard of Sparks when I was studying my 1975 Brownie Handbook. The two white girls on this cover are dancing, wearing their Brownie uniforms and holding hands with pixies, around a toadstool on which a brown owl sits. That uniform with its scarf and pins, that scene of camaraderie: how I longed for that. There was even a way to spell out words using flags, and members could gain a badge for learning how: a seemingly magical way to communicate. After the handbook’s instructional stories, near the end of the volume, the badges shift into focus: |