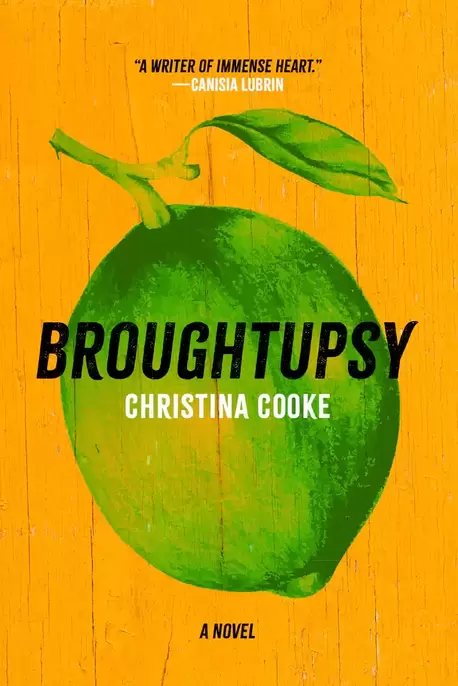

Christina Cooke's BroughtupsyReviewed by Marcie McCauley

Broughtupsy opens with Akúa and her girlfriend Sara stepping through a doorway in Texas; Akúa’s view of the world and her place in it are about to be upended in Christina Cooke’s story of self-discovery.

When twenty-year-old Akúa telephones her sister in distress, Tamika is in Jamaica; the sisters have lived apart for more than a decade. They only briefly lived together with their father in Texas, before Tamika returned to their mother in Jamaica, and, with time and distance, the girls’ resentments and disappointments have accumulated. Readers experience Jamaica through Akúa’s feelings and experiences: “I remember how much I hate this city,” she thinks, when she returns. She’s forgotten how “Kingston can feel so deadening in the afternoon, heat sitting stagnant as though taunting a hurricane to blow it free.” The “chirp of tree frogs” greets readers and we see “vendors selling box lunch and freshly roasted peanuts on the side of the road.” There’s a feeling of time standing still in some instances, the view of “half-built houses with rebars turning red with rustm,” for instance. And a sense of time looping, where “wild goats munch on patches of weeds next to shops closed up behind zinc shutters, graffiti scrawled on top.” Akúa seems to feel both engaged with and apart from these scenes, and sometimes other people—like the customs officer—reflect her ambivalence. “‘Yuh sure is Jamaica yuh come from?’ he says with a chuckle, stamping my passport then signaling to the next person in line.” He stamps her paperwork, but also implies that she doesn’t belong. Although born in Jamaica, she has lived in both the United States and Canada—Texas and British Columbia, respectively—and shared a home with her father and younger brother, Bryson, but not felt at home. Her racialized experiences differed in Canada but prejudices didn’t: “They were much nicer than Texans, I’ll give them that, much calmer and gentler about discovering all the ways I wasn’t like them.” Yet, on returning to Jamaica, not only the customs officer is wary. Even up close, Tamika still feels far away; the sisters’ relationship is tenuous and volatile. Cooke expresses Akúa’s anxiety in simple terms, directly connecting fractures in mind and heart with embodied discomfort. “I turn to her, my questions shattered into splinters burrowing deep into my insides.” What the girls fundamentally share is childhood with their mother (though Tamika lived with her longer). “Anancy and Miss Lou, these were her favorite things,” Tamika muses. (Miss Lou’s children’s shows were televised in Jamaica from 1965 to 1982, presenting the folktales and stories that Jamaican families knew and loved in familiar language and cadence.) Even grown, the girls clung to these broadcasts: figuratively—through memories—and literally—arguing over custody of the video-taped copies. What fundamentally disrupts the sisters’ relationship is Tamika’s response to Akúa’s gender and sexuality, a reflection of the dominant views in the cultural landscape. Akúa doesn’t rely on her emotions to provoke sympathy; she’s aware that her feelings will not outweigh the heteronormative expectations in play, that her ideas about womanhood challenge cultural patterns and religious beliefs. She makes practical arguments instead, for not carrying a purse, for example: “So me must carry purse for thief fi come grab it so?” But Tamika’s inherited distrust reigns. One of the characters in Jamaican-born writer Olive Senior’s The Pain Tree (2015) also writes about the intersection between personal and inherited history, the challenges posed for those caught between: “Now I felt shame, not just for the way I had treated [her], but for a whole way of life I had inherited. It was we who made history, a series of events unfolding with each generation.” Akúa spends enough time in Jamaica to learn the lesson Senior articulates: “What is real is what you carry around inside of you.” Akúa doesn’t take the route a character describes in Pamela Mordecai’s Red Jacket, set on the fictional Caribbean island of St. Chris—“Just pass through, swallow like medicine and press on”—but confronts the past and insists on another kind of future. She finds community that embraces a fluid sense of belonging, in Jamaica, like Francesca Momplaisir describes in The Garden of Broken Things, which opens with a mother returning to Haiti with her teenaged son: “I am a part of it as much as it is a part of me.” The overarching sense is that expressed in Ingrid Persaud’s Love after Love (2020), set in Trinidad and Tobago: “Everybody family have their own problems. Don’t mind what they look like from outside. Inside, all of we going through the same shit.” Akúa’s fractured identity and sense of alienation are not unique; it’s a universal story of locating belonging within one’s own self first, of allowing desire to triumph over disorientation. It’s author Dionne Brand whose words Cooke selects for an epigraph, however. Brand’s own first novel, In Another Place Not Here, was half set in Trinidad and half in Toronto, and introduced characters who loved and lost in both places. Christina Cooke’s Broughtupsy follows in the tradition of novels that invite readers to step over the threshold and insist on fully realised selfhood in the personal space one occupies: an engaging and rewarding debut. Marcie McCauley's work has appeared in Room, Other Voices, Mslexia, Tears in the Fence and Orbis, and has been anthologized by Sumac Press. She writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. A descendant of Irish and English settlers, she lives in the city currently called Toronto, which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples - Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg, Huron-Wendat and Mississaugas of New Credit - land still inhabited by their descendants.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us