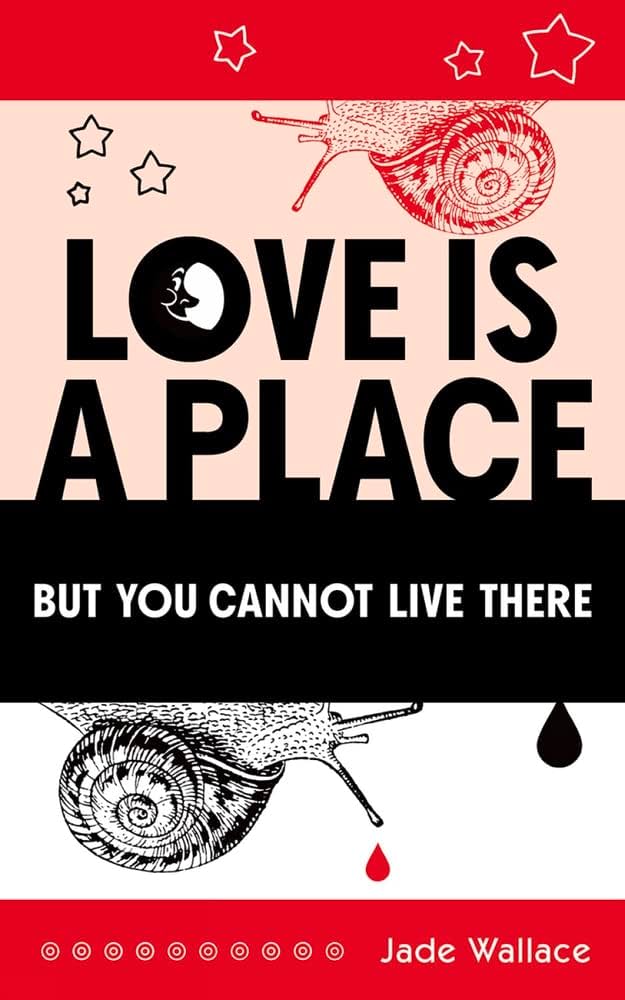

Maria Meindl Interviews Jade WallaceJade Wallace’s writing has won the Muriel’s Journey Poetry Prize and Coastal Shelf’s Funny & Poignant Poetry Contest, placed third in the Ken Belford Poetry Contest, been a finalist for the Wergle Flomp Humour Poetry Prize, and been nominated for The Journey Prize. They are the author of several solo and collaborative chapbooks, most recently Expression Follows Grim Harmony (as MA|DE, Jackpine Press, 2023), as well as the book reviews editor for CAROUSEL and the co-founder of MA|DE, a collaborative writing entity. Love Is A Place But You Cannot Live There is Wallace’s debut poetry collection. Their debut novel, Anomia, is forthcoming with Palimpsest Press in 2024. Keep in touch: jadewallace.ca

After publishing numerous chapbooks, and contributing abundantly to the grassroots literary scene, Jade Wallace published their debut poetry collection, Love Is A Place But You Cannot Live There with Guernica Editions in the spring of 2023. In a Zoom conversation, followed by a lively exchange of emails, we talked about collaboration, alienation, the particularities of cities, and the ubiquitous You.

Maria Meindl: Your new book, Love Is A Place But You Cannot Live There, is about place and relationships. And there’s a nomadic quality to the collection. I’m wondering where the title arrived in your process of writing, and how it all fits with the epigraph by Ann Bannon.

Jade Wallace: The epigraph reads: “It seemed just beyond my reach, something you could see through a window, but you couldn’t pass through. You could visit, but you couldn’t live there.”[1] I found that text quite a while after I decided on the title for the collection, and they coincidentally fit very well together. Ann Bannon herself is an important figure for me. She was well known for writing lesbian pulp novels during the mid-twentieth century, but in her own personal life I don’t think she had such a fixed and settled identity, and this echoes my own experience, as someone who dwells in the ambiguity and elasticity of bisexuality, or queerness, or whatever other circle fits. You’ll notice the love poems in the collection are addressed to people of various genders, or sometimes of no explicit gender. I was, of course, also drawn to the quote, because it resonated with the title I already had, and with a lot of place-based themes that were coming through in the work, and that feeling of longing for things beyond one’s reach. MM: You’d almost say that Ann Bannon was speaking to you from the other side. JW: It did feel like that honestly; actually, a lot of her writing, feels like, for me. MM: Speaking of “The Other Side,” there are a lot of ghosts in this collection. JW: Which is funny because I’ve never actually seen a ghost, never had a direct visceral experience of ghosts. But I’m absolutely fascinated by people who have. MM: I hope you do get the chance to see a ghost sometime. JW: Sometimes I worry that even if I did see one, I would be totally in denial. I’m very agnostic and skeptical about the spiritual in general. But I’m captivated by the lore of ghosts, and I’m open to having my mind changed if ever a ghost sees fit to make themselves known to me. For now, metaphorical ghosts are almost as good. MM: I was drawn to the “Ghost Trip” section because it evokes an area of Southern Ontario that I don’t see enough in literature. Maybe I’m looking in the wrong places. I appreciate the way you portray it in the moments when it’s not showing its public face, shall we say. Can you speak about your relationship to this area? JW: I grew up in Southern Ontario, specifically the Greenbelt of the Niagara region, and I’ve spent my whole adult life in Tkaronto (Toronto) and Windsor. For me Southern Ontario is a formative place, and because this poetry collection is (uncharacteristically) based so heavily on my personal life, it was probably inevitable that the issue of place would be embedded in it, and that this region in particular would be inextricable from the relationships that are unfolding in the poems. People don’t seem to love to talk about Southern Ontario. I get it. It’s not hip. It’s not cool at all. I come from a town that had 50,000 people in it. We had nowhere to hang out. I say, “we,” but what I mean is I walked around by myself and saw other teenagers looking bored when I passed by them. It was kind of a lonely experience. The older I get, though, the more I appreciate how Southern Ontario can be as nuanced and interesting as anywhere else. People here have their folklore, and their interpersonal dramas, and their complex local politics. But also, I come from a blue-collar family. We did take some vacations, but we weren’t going to Europe. A vacation often meant a road trip around Ontario. So Southern Ontario is both home and a place of novelty. Which I think is how I got preoccupied with the idea of psychogeography, as you can you see explicitly in my book’s second epigraph by Ian Buchanan. For him, psychogeography is about “see[ing] the urban space in the light of desire rather than habit.”[2] It’s about the ability to find newness in and be deeply engaged by a mundane place. I feel that everything I do in Southern Ontario has been increasingly psychogeographic over time. MM: The area has a rich cultural history, but there’s also the deeper history. Beneath the playground quality of some of those coastal towns there’s also the thievery of land and the genocide. JW: I completely agree. For me, travelling is never just about going to the place and driving around and being like, “Okay. We’ve seen it.” Whether it’s talking to people who live there or reading texts about the place that you’re visiting, being able to know it on those more complicated levels is important. It’s impossible to read any honest history without encountering, of course, the colonial legacy of Southern Ontario. The poems in the collection are not constantly identifying the Indigenous and colonial histories, but I do acknowledge both of them and critique the latter at various points. I don’t know how you could write about Southern Ontario without being cognizant of those layers. MM: There are travelling companions in this book, too. JW: Yes. My experience of a place is always complicated by the presence of another person. In the New York poems, for example, my mother and I go the city together and, I get to have my experience of New York, but I also get to have her experience of New York by being, to some extent, able to see it through her eyes. Hers becomes one of the many views of the city that permeate my psyche. When I write personal poetry, it’s often because I have something to say to someone that I don’t feel I can ever adequately convey to them in person. Partly because I don’t like to go on long monologues that someone is forced to listen to. But poems give you a space to do that where you’re not burdening the individual with all your thoughts and feelings and insecurities and whatever else. Even in the poems, though, there’s interplay between the descriptions of place, the I speaker, and the You. They’re all constantly bouncing off each other conversationally. This is further complicated by the fact that the identity of the You changes from poem to poem. And even though the poems are not a dialogue, per se, their content is always informed by how I would speak to that You, and by how I think they would respond. I’m always tailoring the poem to that real-life person, even if they’ll never read it. To bring it back to psychogeography: another person’s view of the city gives you access to a perspective on a place that is not informed by your own biases and habits. It’s one way of transcending your own jaded views. I don’t know if it’s a curse of the name, but I feel like I’m often jaded. MM: In the New York poems, the mother is talked about in the third person, but it might as well be “you.” The reader is taken into an inner conversation with the mother. It’s not solipsistic, but still, it is sharing something very interior. JW: That’s true. The poems don’t always have a You, and yet they’re still invisibly structured as if they did. I’m almost always in that pseudo-dialogic space, mentally if not explicitly, when I’m writing. It seems disingenuous to address some universal reader who exists “out there.” Maybe it’s a limitation on my part, but I don’t even know how to write to such a generic person. Communication is relational and I need to be writing to someone in order to find my voice in a poem. MM: So, let’s go to Toronto. I live in Toronto, and I just love watching shows that are set in Toronto: all the leafy streets and the beautiful parks, and cafes. But that’s not the Toronto that you portray in the section called “Northern Edge.” Is there a level of social commentary here? JW: That section was originally written as a collaborative set of poems that I wrote with a person I was living with at the time. One of us would write a poem, then the other would write a response poem, etc. Most of that suite was originally published in a great academic journal called Studies in Social Justice (which is, incidentally, based in Southern Ontario). If you ever read the original suite, you’ll see there’s a rather biting layer of social commentary.[3] And I think there still is, even with the poems being excerpted from their original source. I lived in Toronto for several years after I lived in Niagara, and before I lived in Windsor. I had a very ambivalent experience of it. I think there are a lot of great things about Toronto. There’s a wonderful writing community there for sure and at the same time Toronto is hard on artists because there’s so little of the city that’s actually affordable to live in. I was always up in North York, because that was the cheaper place to live. I originally went there for college, and I had to be really frugal. But even afterwards, when I got a job, I stayed on the fringes of the city so I wasn’t putting my entire pay cheque toward rent. People talk about Toronto being so connected and walkable, and that’s true downtown but it’s a lot less true the farther north you go. I was lucky to live on the edge of the subway line, and yet if I wanted to go to a reading I’d have to work eight hours at my day job, travel an hour and a half downtown for a reading, stay maybe a few hours, then spend another hour and a half to get home just in time to go to bed in order to get up the next day to go to work again. The alienation was multi-layered. There was the alienation of the parts of the city from one another, and the alienation between people. I come from a much, much smaller town, and I was used to having space on the sidewalk when I walked, you know? In Toronto I had a constant sense of—what a friend of mine used to call “friction.” That social friction in Toronto was a real shock to me. There are people around all the time, and you’re all in each other’s way constantly. No one’s friendly, but you’re never alone. The poems in “Northern Edge” really dig into all this and—reading them—I don’t think anyone would be surprised that I left Toronto afterwards. MM: You succeed in this slim volume in taking the mickey out of two major world cities: Toronto and New York. Are there any others in your sights for deflation? JW: Ha! Cities fascinate me but I don’t enjoy living in them. I’m not even sure how much I enjoy visiting them for more than a very brief period. My organism just never adapts to their busy-ness and noise. New York reminded me of Toronto, but on a greater scale. What horrified me about it was the blatant way commercial interests structure large swaths of the city. There is so much that is interesting, artistic, and cultural happening in New York, and yet there’s rampant poverty, and you know that that’s because of where the government decides to spend its money, and which developers it allows to flourish. So many resources sunk into luxury condos and tourist attractions and so little into affordable housing. It’s the veneer of slick, civilized professionalism laid overtop of obvious failures to protect human rights and dignity that disgusts me in every city I’ve ever visited. Of course, it happens in small towns as well, but the scale is so much smaller, the inequity a little less stark. Someone who read my work early on said there’s a kind of meanness in the poems, and I can only imagine they were referring to these city poems. I don’t know if they meant “meanness” as an insult, but I guess I can be kind of harsh sometimes. There are a lot of places in the world I’m not impressed by, and it’s usually because of how they’re managed at the governmental and corporate levels. MM: I don’t know if it’s mean. It’s just not allowing any romanticization. Any pretensions that a city might have are not allowed between these covers. JW: That’s a kind way of looking at it. I just don’t think I can ever be enamored with a place where homelessness is allowed to exist. I’ll never be happy there. It’s always going to bother me. I’m a huge believer in the right to housing, and the provision of affordable housing. There is no reason why, in the middle of all these empty investment properties, there should ever be homelessness, and I just can’t have a good time in a place where that is allowed to happen. MM: The city poems, and some other parts of the collection are quite bleak. But I was delighted to read the richly sensual poems at the end. They’re colorful. They’re whimsical. And there’s a shift in tone. JW: There are indeed a few unequivocally nice poems, at the very end of the last section, “Genius Loci,” that are all interrelated and ironically, all set in Toronto. They represent probably the tenderest memories I have of the city. I wanted to put them at the end as a kind of balm after a book full of grim poems. Because as much as I think it is important to be harsh when necessary—when criticizing the failures of city planning, for example—I don’t want this collection to be a condemnation of human life as a whole. So, I felt a bit of correction was necessary. In “Vanishing Beach,” the section on New Brunswick, there’s a poem where I talk about how even the ocean, which is massive, and powerful, and destructive, also has its moments of “gentleness” I believe that’s true of most things. There is gentleness hidden everywhere. Those nice poems at the end of the book are about finding that gentleness. It’s no accident that they were written at a time when I was coming to terms with my own queerness. I think queerness is an interesting space to inhabit, because it requires such vast relaxation in opposition to rigid normativity. I would never say that queerness is exclusively about softness, by any means, but I think that’s always one aspect of it, because queerness is inherently flexible and expansive with respect to human relationships. It recognizes the primacy of love above and before whatever other rules or mores a society might try to put in place. MM: Can we turn our attention to process? You seem to work very comfortably in collaboration. Can you speak a bit about the solo mode of writing vs. the collaborative? Do they feed each other fight each other? JW: My partner, Mark Laliberte, and I were actually working on a collaborative project earlier today before this interview. I find collaborative writing extremely generative but also extremely fraught. When you’re producing collaboratively you have this wonderful wealth of ideas and mental resources to draw from. You’re drawing from yourself, from the other person, and from the dialogue you have with one another around the work. And at the same time everything is a constant process of compromise. Occasionally you just magically agree on things, and that’s great, but a lot of the time you don’t. Artists can be stubbornly tied to their particular vision of how something should be. It’s easy when you’re writing alone to just be like: “Well, I have this idea in my head, and I’m going to slowly and painfully but inevitably make it appear on the page.” And the only real struggle is with the words themselves. But when you’re writing collaboratively, there’s you, and the page, and this other person, and the ongoing relationship you’ve developed with each other. It’s a rich but also a very difficult space to occupy. I obviously like occupying it. I’ve been collaborating with Mark since 2018 under the name MA|DE. Overall, we manage to be fairly productive—our fourth chapbook, Expression Follows Grim Harmony is coming out with Jackpine Press in August 2023 and our debut collection, ZZOO, is coming out with Palimpsest Press in spring 2025—but today, for example, we had this long argument about how we wanted to approach a particular project. At the same time, there’s a level of accountability, and a sense of purpose when you’re working with another person that can be propulsive. When you’re working on your own stuff, it’s easy to fall into patterns of insecurity: “Is this worth doing? Does this mean anything to anyone except me?” As soon as you involve someone else, well, it means something to them, so you have to just get in and do the work. [1] Attributed to Ann Bannon in Natasha Frost’s article: “The Lesbian Pulp Fiction That Saved Lives” (Atlas Obscura, 2018). [2] Ian Buchanan, A Dictionary of Critical Theory (2nd Edition) (Oxford University Press, 2018) [3] “The Northern Edge of Everything,” Terry Trowbridge and Jade Wallace (Studies in Social Justice, Vol. 12, no. 1. 2018. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v12i1.1664). Maria Meindl is the author of The Work (Stonehouse 2019) and Outside the Box (McGill-Queens 2011), and has had essays, stories, interviews and poetry published in numerous journals (including the Temz Review). In 2005, she founded the Draft reading series, now in its 18th season. She writes and teaches movement in Toronto, and offers a series of monthly lectures called The Work: Straight Talk on Craft and Method, about the suspring histories of today's popular self-care practices. www.mariameindl.com

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us