Interview with Kelly Rose Pflug-BackInterviewed by David Ly

|

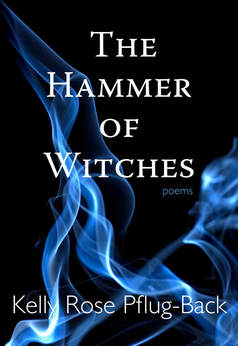

Blending lore and magic with contemporary questions around belief and beauty, power and fear, The Hammer of Witches by Kelly Rose Pflug-Back is a stunning full-length debut, published under Caitlin Press’ Dagger Editions imprint.

What drew me to your collection was the title. What is the inspiration and meaning behind the title of your book, and how did you arrive at it? Malleus Malleficarum, which is most often translated as The Hammer of Witches, was a Catholic treatise that was used to persecute people accused of witchcraft in Europe, beginning in the 1400s. The phrase and concept were circulating around in my thoughts for about four years before I decided to compile about fifteen years’ worth of poems into a manuscript under that title. The original text is filled with such bizarre and fictitious claims, yet it was used to condemn people to agonizing deaths. Something about that speaks to me so much about social exclusion and who is dehumanized enough that no amount of pain and suffering they're subjected to matters in a legal or moral context. One of the men who wrote it was apparently obsessed with the sexuality of the first woman accused of witchcraft, and many of the crimes it details have these sexualized elements to them. So I think it also speaks to the fear of queerness, and of what is perceived as feminine, and the desire to punish and subjugate those things, which I would say is a common theme in my work. As you could probably guess from a lot of the imagery in my poems, I grew up in a very rural area, and there was definitely some conservative Christian influence there. Believe it or not, I was at one point actually the subject of an exorcism. When I was about ten my friend's foster mother said we were going to her house to work on a science project and drove me to the basement of a Pentecostal church instead, and there were all these people speaking in tongues and crowding around me and this one other girl and touching our heads. Queerphobia is something we often start experiencing before we even understand our own queerness, and that's my story about how that played out for me in small-town Ontario. I'd say it's also part of the reason for the fascination with witchcraft, magic, and religion that surfaces repeatedly in this collection. They sure do surface a lot in the collection beautifully, allowing the poems to dance between human connection and magic. My favourite example of this is from the poem “River” where the narrator says, “My ancestors were sea serpents, I told you once / and guided your hands to the frilled crests of bone / that still ridge my skull at the temples.” Could you speak a bit about how you use magical elements to convey moments of closeness, heartbreak, and intimacy? Love and connection are pretty mythic things to me. They're the glue that holds us together, the fuel that drives our actions, and part of the reason we've survived as a species. I get a lot of inspiration from folklore, and for the past year or so I've been studying the Poetic Edda, which is transcriptions of some of the ancient oral traditions of northern Europe. Some of these poems, particularly the Hávamál I would say, revolve around love and relationships and reciprocity. One section says that a person who is not loved will wither like a dying fir tree. We need love to survive, we defy conventions and take risks we might not otherwise because of love, and that's something I think we still have in common with the gods and heroes of these age-old stories. In my eyes, there's something legendary about all of the people I love, and the love I feel for those around me is all the proof of magic existing that I need. When I was growing up, people would call me dramatic or corny because of that, but I wouldn't want to change it about myself. We live in surreal times, where we're watching unprecedented events of ecological destruction unfold. Many of these ancient stories tell us we will only see that scale of destruction happen when the world itself is ending (albeit, so that another one can begin afterwards). So if this isn't a time to love each other more fiercely than ever, I don't know what is. “there's something legendary about all of the people I love.” I love that! I do agree that we need love to survive. I think it helps us grow and change as well. Which brings me to the poem in your collection: “Morning in the Necropolis.” What strikes me in this piece is the transformation of the human body into something fantastical: “the root systems / of necrophagic plants / pulsing, blue / beneath my skin” and “When the next epoch dawns / I will grow a new set of teeth.” I couldn’t help but to draw parallels between our works; the magical transformations we put bodies through in our poems. Could you speak a bit to why this done in your poems, and what you hope it accomplishes? I can definitely see those parallels too! I think in a lot of my poems there's correlations between trauma, queerness, physical illness, and monstrosity. Right now I'm reading We Shall be Monsters, which is an anthology of stories inspired by Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and I love all of the imagery that comes up around the destruction and rebuilding of the self, reclaiming the body from experiences of abuse or control (in many of the stories, the monster must escape their creator and find their own identity), and re-tellings where the monster has a queer, trans, or non-binary identity. In many of my poems, the body sustaining damage or trauma is what allows it to become something new and different. What is seen as fearsome or broken or disfigured about us is also what's magical and monstrous and powerful. So what I hope to accomplish or convey is a message of power and healing, of re-building the self, and of transformation and regeneration always being possible. Whatever we were before is gone, it's a state that we can't return to, and that's okay. That’s beautiful and I completely agree. Some poems in this book are free verse and long. As a poet, when do you consider a “long poem” a poem and not, say, something like flash fiction? Essentially, what is a poem to you? That's a tough one. I am not sure where I would draw the line. The Autumn of the Patriarch, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, is one book that really left an impression on me. The entire thing uses very little punctuation, and is full of very magical, transcendent imagery. So in that sense it's like a prose poem that goes on for hundreds of pages. I wouldn't say there's necessarily a difference to me at a personal level, because I don't always sit down and think of the finished product before I start writing. Although I've done a lot of post-secondary education, none of it actually had to do with creative writing, so I may know less about structure and form than some people. The difference between fiction and poetry occurs to me when that piece of writing is finished and submitted, and I have to confront the fact that it's a lot harder to get something published when it toes the line between being a long poem and a short story. Along with writing and publishing poetry, you also do some journalism. Has writing poetry shaped your approach to journalism in any way, or vice-versa? In a lot of cases, I’m approaching the same subject matter in both poetry and journalism. I've written a few articles on issues relating to the overdose crisis, and in the poems in this collection a lot of the images around grief and loss and death are also about the overdose crisis and the people who I've lost. Some of them also touch on suicide, and are written for other people I've lost. I think the existence of suicide at all in a society is not separable from the oppression and the fundamental problems of that society. And today, it's not separable from the violence we're witnessing being done to the earth either. In poetry there's a lot more room to be lateral. I've tried a few times in non-fiction pieces to address every relating issue, because it's hard for my mind to view anything in isolation, and you're not really allowed to do that in journalism cause there's the issue of scope and what readers and publications have the attention span and the printing space for. So I have to have somewhere to spin those broad webs of connectedness, and poetry is where I can do that. I would say that I need to keep oscillating between both poetry and journalism in order to be able to continue doing either. Well you excel in both genres. What comes first: the title or the poem? Come to think of it, the answer varies. The ones with more interesting titles, had titles that came first. The ones with one-word titles that seem a little tacked-on (to me at least) came to me with no title. I often struggle to think of titles that seem right for those ones, and end up settling in the end for something that never quite seems to fit. Last question: this is your first collection of poetry. Do you have any other creative writing projects in the works at the moment? I do! It was a really validating experience for me having this manuscript published and also getting positive feedback on it. I spent a couple years just totally consumed by the responsibilities of parenting, and I think the 24/7 work of being a caregiver can make a lot of people forget about other parts of their identity, or put those aspects of themselves on hold. I have a few new poems in the works, a folder of unfinished short stories I hope to turn into a collection, a children's book I'm collaborating on with a friend. Photo by Erin Flegg Photography

David Ly is the author of the poetry collection Mythical Man (Anstruther Books, 2020) and the chapbook Stubble Burn (Anstruther Press, 2018). He is the Poetry Editor of This Magazine and sits on the Editorial Collective of Anstruther Press.

|