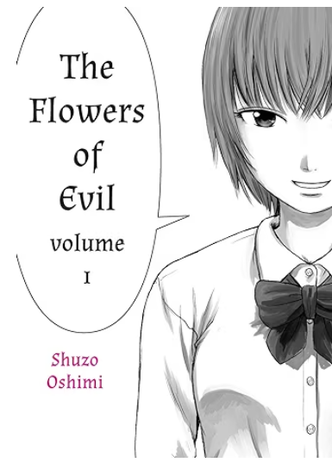

Shuzo Oshimi's The Flowers of EvilReviewed by Anson Leung

Content warning: suicidal ideation

Shuzo Oshimi’s The Flowers of Evil, at first glance, appears to be an average blackmail/love story found in other manga that has been done before. The standard formula has a girl blackmail the male lead in an almost harmless way, and gradually, they fall in love. These Japanese comics in question use this formula as a way to have a self-insert character for the reader to relate to, and to subtly give the reader power. The power would be to win the heart of their former bully/blackmailer. It is a legitimate formula for a love story, and upon further reading, reveals the female “bully” was more complex than she initially led on. The Flowers of Evil, while showcasing these formulae, makes one thing clear from the beginning. The female character, while not hating the main male character, finds nothing remarkable about him in his current state. He lit up her world by stealing a girl’s gym clothes, and this “inner pervert/inner darkness,” at its full potential, is what she relates to. The normal version of him is worthless to her. The romantic portion of the story is already subverted. And that would be the end of the story, except this manga isn’t about love, it’s about psychology. The “love story” of Takao initially trying to hide his perverted act from his classmates and being blackmailed by a girl who loves him, or loves what he could be, is merely the beginning. The meat of the manga series is what happens after the blackmailing arc unfolds. It deals with the fallout and follows the characters deeper into their high-school and eventually adult lives.

The main 5 cast members include the female lead, the unhinged Sawa Nakamura, who’s blackmailing act has less to do with ruining Takao’s life, and more to do with adding a ray of light to hers. Her blackmailing is an attempt to gain a missing fundamental human connection that nobody seems to have with her except for, potentially, Takao. Of course, Takao has to “peel away his layers” and reveal his inner “perverted side”/depraved personality, which the blackmailing plays into. There is also Nanako Saeki, the beautiful girl with unparalleled looks who gets involved with the main character as he heads down his path of darkness. She was the one who left behind her gym uniform, which Takao inadvertently smelled. At some point in the story, Takao confesses his feelings to her. She idealizes Takao since he is the first person to ever confess his love to her, prior to realizing he loves Sawa Nakamura far more. As her friend puts it, she’s in love with the concept of love. Takao’s inability to reciprocate her love, due to favoring Nakamura, unhinges her and causes her to obsess over Takao. Interestingly enough, she loves Takao’s ideal self, a foil to Nakamura craving Takao’s worst self. Nanako’s best friend, Ai Kinoshita, is the main voice of reason, and constantly tries to get Nanako to see her obsessive love for Takao is unhealthy and based on fantasy rather than reality. She actively tries to stop the perverted, and later criminal, activities of Sawa’s and Takao’s escapades. Finally, near the end of the story, Aya Tokiwa, a new love interest, is introduced, and beautifully reconnects the first part of the story to its aftermath, as well as the two inherent stories this manga possesses: the love story and the psychology story. Student-to-student interactions within the school are merely generic interactions found in other manga. Discussing topics such as boys and schoolwork, they do nothing to advance the plot. They act as “padding” to the manga. While there is nothing wrong with these interactions, they are not especially well written. On the other hand, the interactions between the main character and his parents show nuanced emotions on the characters’ faces. When Takao is hiding something from them, they can read between the lines and see when something is wrong. Takao tries to hide the borderline criminal escapades he commits under the blackmail from Nakamura. They don’t suspect he is doing anything wrong, initially. But the moment they do, they silently build up their worry. Due to their son’s distant behavior, they slowly show signs of being worn out, such as the subtle increase in facial hair on the father’s face. The author ensures that both dialogue and background drawings hint at an increased use of cigarettes and alcohol in the father’s diet. The audience gets a feeling that the parents are tired, but it’s more of an uncomfortable, nagging feeling, rather than an overpowering one. The moment Takao in high school confesses his love to Awa Tokiwa and starts to move past the trauma from an attempted mutual suicide he shared with Sawa at the end of Part 1 of the series, he merely utters the words, “I’m home”. The father understands the nuance. Very shortly after, the father is back to being clean-shaven. On the flip side, the moment Takao encounters hardship in his high school days by briefly re-meeting Nanako, Takao starts to have negative emotions. His father picks up on this almost immediately without Takao even referencing Nanako in their conversation. His eyes widen without confronting Takao on the issue. The main villain in this story is Nakamura, though she is more amoral than evil. She blackmails Takao to fulfill her own emotional needs. Takao was literally her light in her world, as the final chapter shows us. With this being said, the main conflict isn’t an evil villain to overcome, as Nakamura was simply being selfish as opposed to doing the blackmailing for the purpose of hurting Takao. Takao was performing his acts of depravity under the threat of blackmail to initially stop Nanako from finding out he sniffed her gym clothes. Later, this mindset shifted to keeping Nakamura by his side as he fell more in love with her than his superficial crush on Nanako. His destructive acts no longer become somebody else’s fault, not entirely. The main conflict shifts from escaping the blackmailing, to becoming a conflict with society, since nobody finds their behavior normal. They perform perverted and depraved acts such as stealing other girls’ gym clothes, vandalizing the classroom, and anything else they can think of to reach “the other side”, a place that will grant Nakamura a permanent escape from the bleak view that encapsulates her life. They keep their criminal activities a secret from everybody else so they can keep trying to reach “the other side”. “The other side” is a main focal point of this novel. It drives the behavior of Nakamura because she tries to escape to it. Initially, they try to literally go to the “other side” of their small town with their bikes, thinking that the town’s small size and lack of activities is the cause of their malaise. They shift their focus on their depraved, perverted activities to reach “the other side”, because they acknowledge it is a feeling rather than a geographical destination. To reach this feeling, they escalate their depravity until Nakamura realizes that even at its best, they will not be enough to reach “the other side”. With the failure to reach “the other side” through both geographical means and depraved activities, a dejected Nakamura realizes that even the most perverted form of Takao cannot bring her happiness. For all the literal color shown in the final chapter he brought into her life, her best hope for a better life is still not enough to allow her to reach “the other side”. With nothing left to live for, she tries to order Takao to smash her head with a baseball bat. Takao offers to commit suicide with her. She pushes Takao away at the last moment, not wanting him to die with her. Likewise, Takao doesn’t want her to die once he comes back to his senses. This is a part of the series I do not like. She survives and somehow finds happiness by moving to a different town to live with her mother. Geographical distance does not allow one to find “the other side”, and if one argues emotionally that she is happy because she is living with her mother, then why push the main character to such depravity in the pursuit of color, in the pursuit of beauty, in her life? Why go down the road Baudelaire’s novel The Flowers of Evil was trying to convey, and attempt to find beauty in depravity, when one can find beauty in family? Her motives at the beginning of the series did not appear easily solvable. She literally saw the world in black, shadows, and several hundred literal flies, until Takao filled it with color after sniffing Nanako’s gym uniform and showing a common connection of hidden perverted behavior that both Takao and Nakamura share. This route was a cop-out. The incorporation of The Flowers of Evil was done well. The main character read the book several times and understood it, albeit superficially. A recurring motif of the evil eye illustrated in Charles Baudelaire’s book shows itself permeating Takao’s thoughts. Mainly, it was used to show Takao’s mental state, and how perverse his mindset is at any given time, depending on how wide the eye opened. The idea behind The Flowers of Evil was to show that there is beauty in evil as long as it is expressed poetically. A small downside is that the reader of the manga would have to read Baudelaire’s book first, or at least a summary page, to understand it. One wonders why the protagonists couldn’t simply find other forms of beauty. A small town would still have flower shops, and their family backgrounds are normal enough to prevent perverse acts from being the first source of beauty they find. A bit contrived, in my opinion. The Flowers of Evil is a manga series that hooks you with its psychology. The facial expressions are first-rate, and while the reader has to familiarize themselves with Baudelaire’s book in order to fully appreciate the story, it is well worth it. Anson Leung is a graduate of the University of Alberta’s Bachelor of Commerce program. He is an Alberta based writer who loves all forms of writing, including poetry and article writing. In his spare time, he loves playing tennis and board games.

|

- Home

- Issue Twenty-Seven

- Submissions

- 845 Press Chapbook Catalogue

-

Past Issues

- Issue Twenty-Six

- Issue Twenty-Five

- Issue Twenty-Four

- Issue Twenty-Three

-

Issue Twenty-Two

>

- Fiction: JACLYN DESFORGES

- Fiction: Cianna Garrison

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Jade Green

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Sveta Yefimenko

- Nonfiction: Carol Krause

- Nonfiction: Charmaine Yu

- Poetry: Naa Asheley Afua Adowaa Ashitey

- Poetry: Jes Battis

- Poetry: Jenkin Benson

- Poetry: Salma Hussain

- Poetry: Stephanie Holden

- Poetry: Daniela Loggia

- Poetry: D. A. Lockhart

- Poetry: Ben Robinson

- Poetry: Silvae Mercedes

- Poetry: Olivia Van Nguyen

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antonio (Accardi)

- Review: Anson Leung (Kobayashi)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Dupont)

- Review: Khashayar Mohammadi (Frost)

- Interview: Berg

- Issue 22 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty-One

>

- Fiction: Joelle Barron

- Fiction: A.C.

- Fiction: Blossom Hibbert

- Fiction: Shih-Li Kow

- Fiction: William M. McIntosh

- Fiction: Tina S. Zhu

- Poetry: Adamu Yahuza Abdullahi

- Poetry: Frances Boyle 21

- Poetry: Atreyee Gupta

- Poetry: [jp/p]

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird 21

- Poetry: J.A. Pak

- Poetry: Bryan Sentes

- Poetry: Melissa Schnarr

- Poetry: Jordan Williamson

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Pirani)

- Review: Alex Carrigan (Di Blasi)

- Review: Margaryta Golovchenko (Bandukwala)

- Review: Anson Leung (Waterfall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Astur)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Chaulk)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Welch)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wallace)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Eco)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Wu)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (De Gregorio)

- Issue 21 Contributors

-

Issue Twenty

>

- Fiction: Shaelin Bishop

- Fiction: Nicole Chatelain

- Fiction: Sarah Cipullo

- Fiction: Sarah Lachmansingh

- Fiction: Taylor Shoda

- Fiction: Katie Szyszko

- Fiction: Sage Tyrtle

- Poetry: Noah Berlatsky

- Poetry: Janice Colman

- Poetry: Farah Ghafoor

- Poetry: Gabriela Halas

- Poetry: Luke MacLean

- Poetry: Maria S. Picone

- Poetry: Holly Reid

- Poetry: Misha Solomon

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Tad-y)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Clayton)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Lockhart)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Woo)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Sederowsky)

- Review: Terry Trowbridge (Huth)

-

Issue Nineteen

>

- Fiction: K.R. Byggdin

- Fiction: Lisa Foley

- Fiction: Katie Gurel

- Fiction: JB Hwang

- Fiction: Danny Jacobs

- Fiction: Harry Vandervlist

- Fiction: Jules Vasquez

- Fiction: Z. N. Zelenka

- Interview with Randy Lundy

- Poetry: Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arówólò

- Poetry: Leah Duarte

- Poetry: Elianne

- Poetry: Ewa Gerald Onyebuchi

- Poetry: Marc Perez

- Poetry: Natalie Rice

- Poetry: Sunday T. Saheed

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (roberts)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Mello)

- Review: Ben Gallagher (Nguyen and Bradford)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Fu)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Koss)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Heti)

- Issue Nineteen Contributors

-

Issue Eighteen

>

- Poetry: Jenny Berkel

- Poetry: Kyle Flemmer

- Poetry: Chinedu Gospel

- Poetry: Olaitan Junaid

- Poetry: Jane Shi

- Poetry: John Nyman

- Poetry: Samantha Martin-Bird

- Poetry: Carol Harvey Steski

- Poetry: Kevin Wilson

- Interviews: Mohammadi, Barger & Do

- Fiction: Duru Gungor

- Fiction: Darryl Joel Berger

- Fiction: Grace Ma

- Fiction: Hannah Macready

- Fiction: Avra Margariti

- Fiction: Shelley Stein-Wotten

- Fiction: Laura Hulthen Thomas

- Fiction: Lucy Zhang

- Review: ALHS (Carson)

- Review: Manahil Bandukwala (Janmohamed)

- Review: Padmaja Battani (Conlon)

- Review: Carla Scarano D'Antanio (Henning)

- Review: Leighton Lowry (Wall)

- Review: Marcie McCauley (Butler Hallett)

- Review: Jérôme Melançon (Cheuk)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Tynianov)

- Review: Nicole Yurcaba (Mathieu)

- Issue Eighteen Contributors

-

Issue Seventeen

>

- Review: Jeremy Luke Hill

- Review: Marcie McCauley

- Review: Erica McKeen

- Review: Malaika Nasir

- Review: Carla Scarano

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Flemmer)

- Review: Aaron Schneider (Svec)

- Review: K. R. Wilson

- Poetry: Manahil Bandukwala

- Poetry: Paola Ferrante

- Poetry: Hollay Ghadery

- Poetry: Dawn Macdonald

- Poetry: Charles J. March III

- Poetry: Anita Ngai

- Poetry: Renée M. Sgroi

- Fiction: Ben Berman Ghan

- Fiction: Rosalind Goldsmith

- Fiction: Aaron Kreuter

- Fiction: Rachel Lachmansingh

- Fiction: J Eric Miller

- Interview: David Ly and Jaclyn Desforges

- Interview: Kevin Heslop and Michelle Wilson

- Issue Seventeen Contributors

- Issue Sixteen >

-

Issue Fifteen

>

- Hollie Adams

- Amy Bobeda

- Leanne Boschman

- Kim Fahner

- Maryam Gowralli

- Adesuwa Okoyomon

- Nedda Sarshar

- Boloere Seibidor

- Kevin Spenst

- Tara Tulshyan

- Denise André

- Mark Bolsover

- Sam Cheuk

- Elena Dolgopyat and Richard Coombes

- MJ Malleck

- Katie Welch

- Ly and Sookfong Lee

- Heslop and Wang

- Scarano D'Antonio Santos

- Schneider Lyacos

- Issue Fifteen Contributors

- Issue Fourteen

- Issue Thirteen

- Issue Twelve

- Issue Eleven

- Issue Ten

- Issue Nine

- Issue Eight >

-

Issue Seven

>

- Anne

- Dessa Bayrock

- Fraser Calderwood

- Charita Gil 7

- Carol Krause

- D. A. Lockhart

- Terese Mason Pierre

- McCauley Shidmehr

- Michael Mirolla

- Anna Navarro

- Chimedum Ohaegbu

- Matt Patterson

- Scarano D'Antonio Arthur

- Schneider Woo

- Matthew Walsh

- Finn Wylie

- Lucy Yang

- Andrew Yoder

- Yuan Changming

- Issue Seven Contributors

-

Issue Six

>

- O-Jeremiah Agbaakin

- Sydney Brooman

- Mark Budman 6

- Christopher Evans

- JR Gerow

- Jeremy Luke Hill

- Ada Hoffmann

- Tehmina Khan

- Keri Korteling

- Michael Lithgow 6

- David Ly 6

- McCauley Thapa

- Kathryn McMahon

- Rosemin Nathoo

- Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

- Carla Scarano D'Antonio Review

- Schneider Kreuter

- Schneider Mills-Milde

- Seth Simons

- Christina Strigas

- Issue Six Contributors

-

Issue Five

>

- Wale Ayinla

- Sile Englert

- Kathy Mak

- Alycia Pirmohamed

- Ben Robinson

- Archana Sridhar

- Ojo Taiye 5

- Isabella Wang

- Vince Blyler

- Becca Borawski Jenkins

- Sonal Champsee

- Saudha Kasim

- Heslop and Boswell

- McCauley Grimoire

- Mitchell Baseline

- Mitchell Self-Defence

- Schneider Guernica

- Schreiber Wave

- Watts Alfred Gustav

- Issue Five Contributors

-

Issue Four

>

- Joanna Cleary

- John LaPine

- Michael Lithgow

- Andrea Moorhead

- Adam Pottle

- Brittany Renaud

- Gervanna Stephens

- Alvin Wong

- Charita Gil

- Robert Guffey

- Albert Katz

- Maria Meindl

- Sam Mills

- Heslop and Cull

- Mitchell Downward This Dog

- Mitchell Tower

- Schneider Bad Animals

- Schreiber What Kind of Man Are You

- Issue Four Contributors

- Issue Three >

- Issue Two >

-

Issue One

>

- Paola Ferrante - "Wedding Day, Circa My Mother"

- Jeff Parent - "Cancer Sonnet"

- M. Stone - "Upcycle" and "Foresight"

- Erin Bedford - "Clutch"

- Téa Mutonji - "The Doctor's Visit"

- Peter Szuban - "The Ghost of Legnica Castle"

- Obinna Udenwe - "All Good Things Come to an End"

- Monica Wang - "In the Lakewater"

- Tara Isabel Zambrano - "Hospice"

- Lindsay Zier-Vogel - "You Showed Up Wearing Pants"

- Amy Mitchell - Review of Lisa Bird-Wilson's Just Pretending

- Issue One Contributors

- About Us